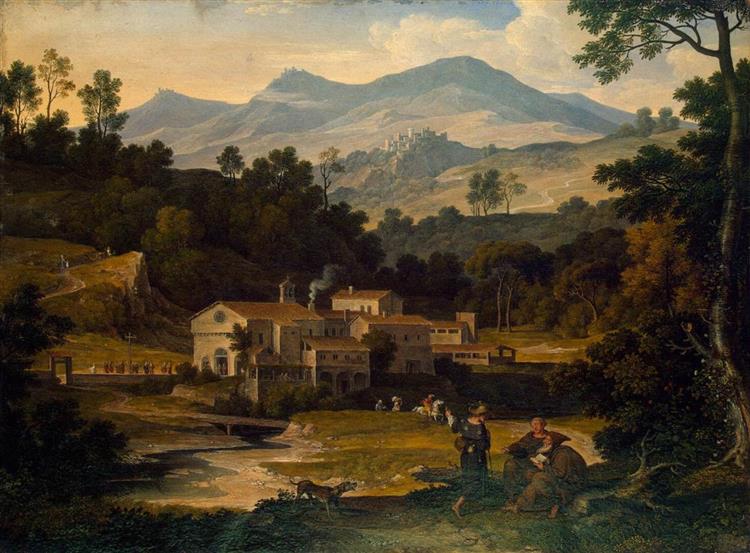

Heiligenstadt 19th century by Anon

7 Bagatelles Op.33 for piano (1802, Beethoven aged 31)

1. Andante grazioso quasi allegretto (E♭ major)

2. Scherzo – Allegro (C major)

3. Allegretto (F major)

4. Andante (A major)

5. Allegro ma non troppo (C major)

6. Allegretto quasi andante (D major)

7. Presto (A♭ major)

Dedication not known

Duration 20′

Listen

written by Ben Hogwood

Background and Critical Reception

1802 was a key year for Beethoven. Suffering from ill health and from the disintegration of his hearing, he was instructed by his doctor to leave Vienna for the nearby village of Heiligenstadt, to aid his convalescence.

Sadly his health did not improve, giving to the famous Heiligenstadt Testament, where the composer bared his soul in a letter to his brothers. The correspondence was sealed but not delivered or seen until after Beethoven’s death.

Despite (or in spite of) going through such a tragic time, Beethoven redoubled his efforts as a composer, focusing all his energies into new work. Around this time he turned to the Bagatelle, a short form of piano piece, collecting his first volume of seven miniatures in a folder and publishing them as Op.33 in 1803. Each lasts two or three minutes.

The collection consists of ideas going right back to the composer’s early music from Bonn, and may (writes Misha Donat for Hyperion) include music written as long ago as 1782, used for the first piece of the seven. ‘Perhaps the intricate, improvisatory runs that embellish the main theme (they become more elaborate with each appearance) were a later addition’, he says. Summing up, ‘the two jewels of the set are, perhaps, the much more relaxed and lyrical fourth and sixth numbers.’

Thoughts

The Bagatelles are great fun. The first piece enjoys leaning on its dissonances – a friendly, welcoming way in. It also hangs around in the listener’s head, its main tune being unexpectedly catchy. The second is lively too, firstly adopting the profile of an offbeat march, but then rumbling into A minor for a fulsome second idea. Beethoven is enjoying himself – and continues to do so more subtly in no.3. This is a popular student piece (which I have had the joy of playing) and is simple but wonderfully effective, springing a subtle surprise when the music suddenly but effortlessly turns the music from F major into D major.

The fourth bagatelle is indeed more relaxed, bringing reminders of Mozart with its graceful air, though clouds appear briefly in the minor key middle section. By contrast the fifth is a torrent of notes, asking questions when it pauses but emphatically answering them with a cascade down the keyboard. The sixth relaxes a bit more, an appealing conversational piece. Finally we get a sneak preview of the figuration Beethoven is to return to in the Waldstein sonata, the last bagatelle generating manic energy.

Recordings used and Spotify playlist

Alfred Brendel (Philips)

John Lill (Chandos)

Paul Lewis (Harmonia Mundi)

Glenn Gould (Sony Classical)

Ronald Brautigam (BIS)

A wide range of approaches here, from Ronald Brautigam’s crisp staccato on the fortepiano to Alfred Brendel’s peerless phrasing and poise. Outside of these lies Glenn Gould, a fascinating and engaging listen. His style sounds very prim and proper to begin with but once the ear adjusts it is actually very appealing, and he lingers lovingly over the dissonances of no.1. John Lill and Paul Lewis, last but certainly not least, enjoy the music greatly.

You can also hear clips of Steven Osborne’s recording at the Hyperion website

You can chart the Arcana Beethoven playlist as it grows, with one recommended version of each piece we listen to. Catch up here!

Also written in 1802 Titz 3 String Quartets

Next up Romance no.1 in G major Op.40