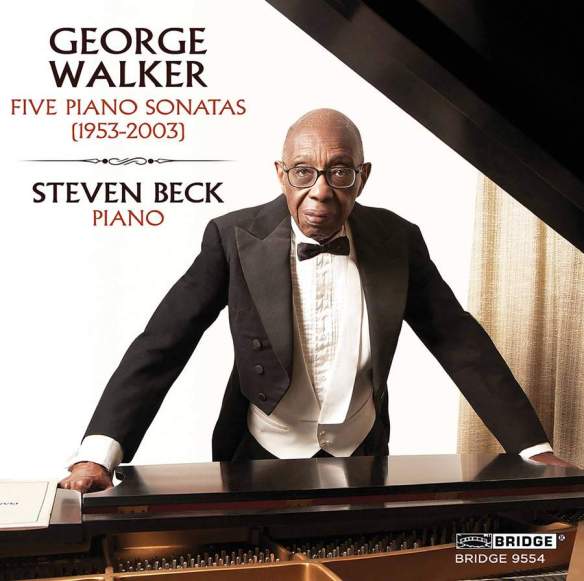

Steven Beck (piano)

George Walker

Piano Sonatas: no.1 (1953, rev. 1991); no.2 (1956); no.3 (1975, rev. 1996); no.4 (1984); no.5 (2003)

Bridge 9554 [53’13”]

Producer Steven Beck

Engineer Ryan Streber

Recorded 4 & 14 February 2021 at Oktaven Audio, Mount Vernon, NY

Reviewed by Richard Whitehouse

What’s the story?

Bridge continues its wide-ranging coverage of American music with this release featuring all five of the piano sonatas by George Walker (1922-2018), a composer who is now coming into his own on this side of the Atlantic and through, one trusts, the intrinsic quality of his music.

What’s the music like?

Although he achieved success in the USA, with commissions from several leading orchestras and a Pulitzer Prize in 1996 (making him its first black recipient), Walker was little known in the UK until recently – other than Natalie Hinderas’s account of his Piano Concerto in CBS’s ground-breaking Black Composers Series from the 1970s and occasional revival of his Lyric for strings (the most played such piece in America after Barber’s Adagio). That the current Proms season featured no less than three of his works is hopefully in itself a positive sign.

With its antecedents in Copland and Piston, the First Sonata appeared at a time of incipient change for American music – its three movements classically conceived but never adhering to formal archetypes; witness the flexible handling of sonata principles in the initial Allegro, followed by the contrasted sequence of six variations on a winsome folk tune, then dextrous contrapuntal texture and cumulative impetus of the rondo which comprises its final Allegro. Barely three years later, the Second Sonata sounds as if it might be responding to Sessions’s ‘transitional’ music of not long before – its initial movement’s theme the basis of 10 gnomic variations, followed by a Presto as brief as it is virtuosic, then an Adagio circumspect in its restiveness, and an Allegretto ensuring a degree of finality for all its harmonic ambivalence.

Almost two decades on and the Third Sonata postdates Walker’s most intensive involvement with serialism, but it does not eschew innovation – whether in the constantly metamorphosed shapes of the opening Phantoms, distanced yet ominous emotional resonance of the central Bell, or those myriad textural contrasts which build considerable momentum in the closing Choral and Fughetta. In the Fourth Sonata, number of movements may be further reduced but the emotional range is further extended – the forceful if never unyielding rhetoric of its Maestoso ideally complemented with the formal and expressive disjunction of its Tranquillo. Outwardly a concert study, the Fifth Sonata has as emotional impact out of all proportion to its brevity while leaving little doubt as to Walker’s creative prowess during his ninth decade.

Does it all work?

Almost always. As dates of composition suggest, these sonatas afford a viable (not inclusive) overview of Walker’s evolution – responding to the aesthetic changes in post-war American music methodically and resourcefully, without detriment to his creative integrity. It helps that Steven Beck is as audibly attuned to this music as to that by other US composers – rendering these pieces with precision and commitment, but the recording might have had a degree more warmth to complement its unfailing clarity. Succinctly informative notes from Ethan Iverson.

Is it recommended?

It is. All these sonatas have previous been recorded (notably as part of the extensive coverage on the Albany label), but this release is a clear first choice for anyone coming to them afresh. Hopefully Bridge will record further Walker – maybe an integral cycle of his five Sinfonias?

For further information on this release, visit the Bridge Records website, and for more on George Walker click here. You can read more about Steven Beck on his website

written by Richard Whitehouse

written by Richard Whitehouse