Listening to Beethoven #197 – Polyphonic Italian Songs WoO 99

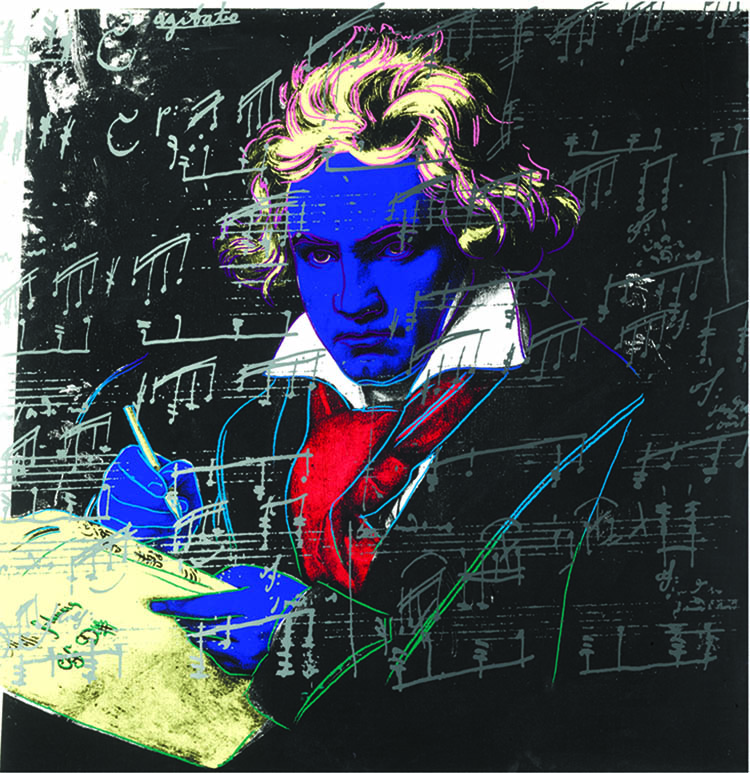

Beethoven (1987) by Andy Warhol – colour screenprint on Lenox Museum Board

Piano Concerto no.3 in C minor Op.37 for piano and orchestra (1796-1803, Beethoven aged 32)

Dedication Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia

Duration 37′

Listen

Background and Critical Reception

Beethoven is thought to have begun the third piano concerto as early as 1796, finishing the majority of the work in 1800 but waiting until 5 April 1803 for the first performance at the Theater an der Wien in Vienna. It was quite a concert, beginning with the Symphony no.2 and ending with the newly composed Christus am Ölberge, in its first version.

Beethoven had to rush the concerto to get it ready in time, and as a result the solo part was unfinished. An account from the composer’s friend and page turner Ignaz von Seyfried found him effectively turning empty pages during the first concert, Beethoven having committed the solo part to memory.

Many writers recognise the lineage of this work. Charles Rosen, in The Classical Style writes, “The C minor is full of Mozartean reminiscences, in particular of the concerto in the same key, K491, which Beethoven is known to have admired.” Barry Cooper, writing for Hyperion, notes that ‘there is little, if any, direct influence from Mozart’s work, although the similarities show how thoroughly Beethoven had absorbed Mozart’s style.’

The first movement is Beethoven’s weightiest movement yet, clocking in at over 17 minutes in some performances. It is followed by a Largo in the unexpectedly remote key of E major, which would have come as a surprise to the audience in 1803. This tonality is referred to in a ‘dream-like recall’ in the finale (writes William Kinderman). This movement is a Rondo, where after some tense episodes in the minor key, Kinderman writes how “comic wit and jubilation crown the dénouement of this drama in tones”.

Perhaps surprisingly, one of the most guarded verdicts on the third concerto came from Brahms. Comparing it to the Mozart, “a marvellous work of art and filled with divine ideas”, he said “I admit that the Beethoven concerto is more modern…but it is not significant!”

Thoughts

The third of Beethoven’s five published piano concertos is a different animal entirely from the first two. Confirmation of this is felt in the opening bars, with a tense first theme outlined by the strings. Whereas the first two concertos were light on their feet and relatively frothy, this one has a serious countenance, like its counterpart C minor concerto from Mozart in 1784.

The comparisons made between the two are certainly valid, for they occupy a similar emotional space and use almost identical orchestral forces. Beethoven tends to focus in on daring harmonies, creating tension between his much-used C minor and the major key. The soloist has some juicy discords too, to keep the listener on the edge of their seat.

The drama starts with that first theme on the strings and does not let up in the first movement, which despite its length is tautly argued. The arrival of the piano, with stern scales in C minor, is arresting, and in his own written-out cadenza completed in 1808 Beethoven brings in the intimacy of his sonatas, before a series of trills lead to a sparse conclusion from the orchestra. I think Brahms was doing it a disservice!

Perhaps the biggest raise of the eyebrows, however, comes with the first notes of the slow movement, which introduces a whole new key of E major. It is a surprise to the ear which, taking previous examples from the composer, might expect A flat major or F. Beethoven uses this new area to explore a thoughtful, tender side, giving himself and the solo pianist free reign. There is mystery and poetry here, and some sublime contributions from the orchestra.

The final movement is where Beethoven and Mozart are closer aligned, with quite an oblique melody that becomes surprisingly catchy – and which completes its own ‘darkness to light’ journey in the closing passages. The composer even works in a short fugal episode to the energetic movement with effortless ease. In this piece Beethoven has served notice of his intentions to move the piano concerto on to more Romantic territory, both in musical style and emotion.

Spotify playlist and Recordings used

Wilhelm Kempff, Berliner Philharmoniker / Ferdinand Leitner (Deutsche Grammophon)

Robert Levin, Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique / Sir John Eliot Gardiner (Arkiv)

Mitsuko Uchida, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra / Kurt Sanderling (Philips)

Rudolf Serkin, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra / Rafael Kubelik (Orfeo)

Claudio Arrau, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra / Bernard Haitink (Philips)

Ronald Brautigam, Die Kölner Akademie / Michael Alexander Willens (BIS)

Stephen Hough, Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra / Hannu Lintu (Hyperion)

Stephen Kovacevich, BBC Symphony Orchestra / Sir Colin Davis (Philips)

There are some wonderful accounts of this piece. While writing about the work I have especially enjoyed the versions with soloists Mitsuko Uchida, Wilhelm Kempff and Stephen Kovacevich, while on the fortepiano Robert Levin creates lean drama with Sir John Eliot Gardiner. Uchida is magical at the beginning of the slow movement, which becomes the dream Beethoven surely meant it to be.

To listen to clips from Stephen Hough’s new recording on Hyperion, head to their website

You can chart the Arcana Beethoven playlist as it grows, with one recommended version of each piece we listen to. Catch up here!

Also written in 1803 Boieldieu Clarinet Concerto no.1 in E flat major Op.36

Next up Bei labbri, che Amore WoO 99/1

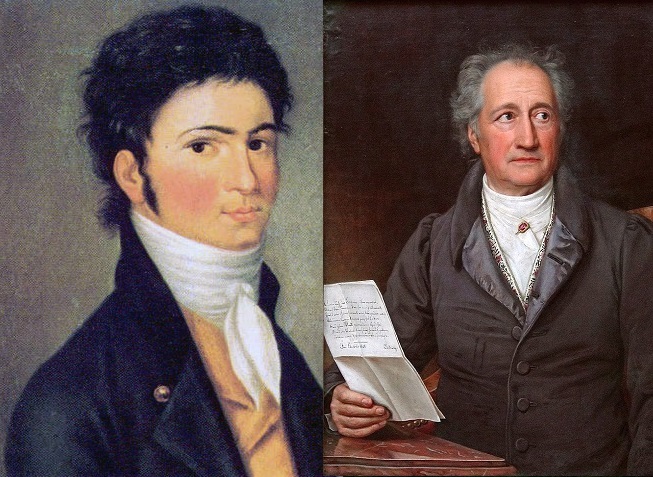

Beethoven and Goethe

6 Variations on Ich denke dein WoO 74 for two pianos (1799-1803, Beethoven aged 31)

Dedication Therese, Josephine and Charlotte von Brunsvik

Duration 5′

Listen

Background and Critical Reception

Keith Anderson writes that in 1799, Beethoven ‘wrote a setting of Goethe’s Ich denke dein and four variations for piano duet on the theme for two pupils, the Countesses Therese and Josephine Brunsvik, daughters of a family with which Beethoven remained friendly through much of his life. In 1803 he added two more variations and the song and variations were published in 1805.

Pianist Peter Hill, writing for a recent recording he made with Benjamin Frith on the Delphian label, highlights Beethoven’s affection for Josephine, expressed in a passionate letter later in his life. He notes the romantic mood of the theme and its variations, pointing towards Mendelsssohn in the faster music especially.

Thoughts

As the story implies, this is a domestic piece for use among close friends. It certainly has that intimate, conversational feel, with less obvious opportunities for virtuosic display but plenty to keep the players occupied and impressed with Beethoven’s resourceful working.

The theme itself is warm hearted, the first variation too. Then Beethoven plays around with syncopations, the two players gainfully employed, before a thoughtful, slow third variation, which is unexpectedly deep in feeling. This time out enhances the fourth variation, a fizzy affair with exchanges between the two players which drew the Mendelssohn comparison from Peter Hill. Darker colours appear briefly for an instalment in the minor key, after which the sunlit textures of D major return and the piece ends calmly but warmly, providing a glimpse of an all-too rare warmth and tenderness in Beethoven’s life at the time.

Recordings used and Spotify playlist

Peter Hill & Benjamin Frith (Delphian)

Amy and Sara Hamann (Grand Piano)

Louis Lortie & Hélène Mercier (Chandos)

Jörg Demus & Norman Shetler (Deutsche Grammophon)

All excellent versions, capturing the intimacy of Beethoven’s writing but also the glint in the eye as he writes.

Also written in 1803 von Pasterwicz 300 Themata und Versetten Op.42

Next up Piano Concerto no.3 in C minor Op.37

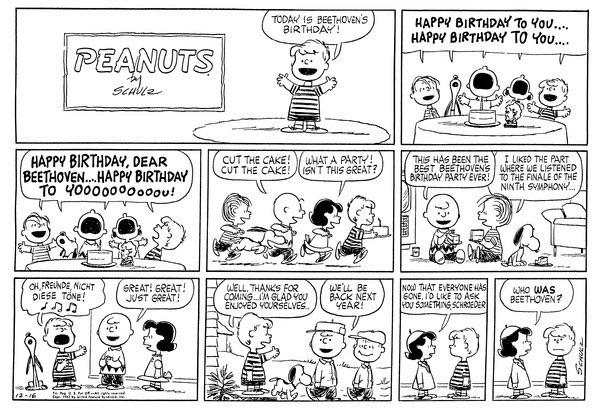

Peanuts comic strip, drawn by Charles M. Schulz (c)PNTS

Peanuts comic strip, drawn by Charles M. Schulz (c)PNTS

Graf, liebster Graf, liebstes Schaf WoO 101 for three voices (1802, Beethoven aged 31)

Dedication Count Nikolaus Zmeskall von Domanovecz

Text Beethoven

Duration 0’45”

Listen

Background and Critical Reception

This is one of Beethoven’s early musical jokes, which he included in a letter to his friend, Count Nikolaus Zmeskall von Domanovecz. The short text translates as ‘Count, Count, dear Count, best sheep!’

Thoughts

Literally scribbled on the back of an envelope, this is a charming fragment – cleverly working the pronunciations into the melody. Very much a case of less is more!

Recordings used

Cantus Novus Wien / Thomas Holmes (Naxos)

Coro della Svizzera / Diego Fasolis (Arts Music)

Also written in 1802 Reichardt Das Zauberschloss

Next up 6 variations on Ich denke dein WoO 74

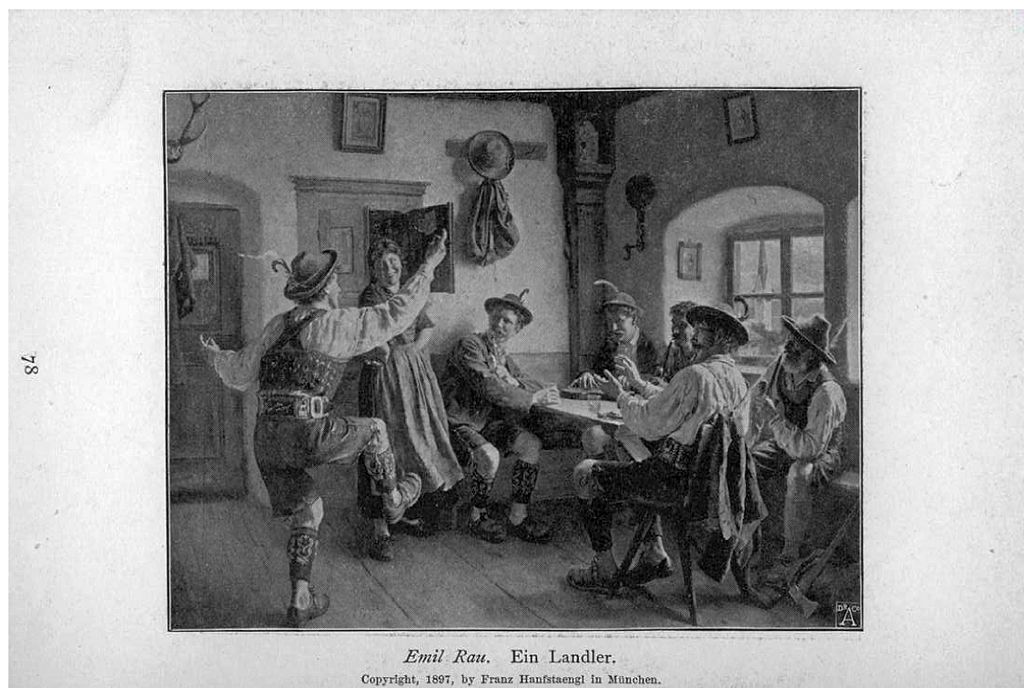

Ein Landler (anon, 1897)

6 Ländler WoO 15 for piano (1802, Beethoven aged 31)

Dedication unknown

Duration 6′

written by Ben Hogwood

Listen

Background and Critical Reception

Beethoven often turned to the Ländler, a folk dance in 3/4 time, as a way of helping entertain his Viennese clientele. He was able to score them for different instrumental combinations, presumably in response to the circumstances of the entertainers. This set is originally for two violins and a bass instrument – but as with many of these dances was also reworked into a piano version.

Thoughts

The piano version of these dance pieces brings out the ‘drone’ qualities in the accompaniment more. These can be heard on the first beat of the bar, where the left hand of the piano typically plays in intervals of a fifth, the support on which the more rhythmic elements of the dance can work their magic.

Recordings used and Spotify links

Jenő Jandó (Naxos)

Martino Tirimo (Hänssler)

Both versions are nicely played, bringing out the spring in Beethoven’s step.

Also written in 1802 Förster 3 String Quartets Op.21

Next up Graf, liebster Graf, liebstes Schaf WoO 101