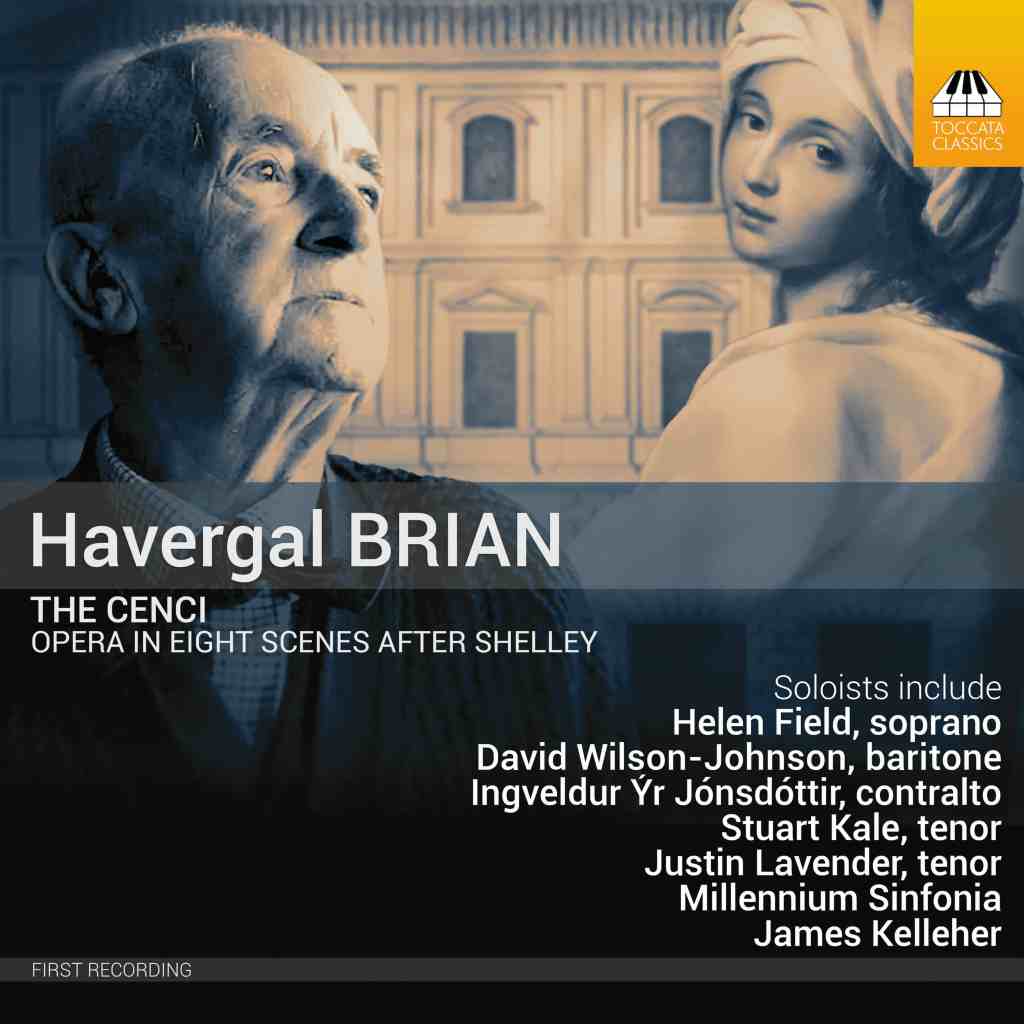

Brian

The Cenci (1951-2)

Helen Field (soprano) Beatrice Cenci

David Wilson-Johnson (baritone) Count Cenci

Ingveldur Ýr Jónsdóttir (contralto) Lucretia

Stuart Kale (tenor) Cardinal Camillo/An Officer

Justin Lavender (tenor) Orsino/Bernardo

Jeffrey Carl (baritone) Giacomo/Savella/First Judge/Second Judge

Nicholas Buxton (tenor) Marzio/Third Guest/A Cardinal

Devon Harrison (bass) Olimpio/Colonna/Third Guest

Serena Kay (soprano) First Guest/Second Guest

The Millennium Sinfonia / James Kelleher

Toccata Classics TOCC0094 [two discs, 101’32’’]

Producer & Engineer Geoff Miles Remastering Adeq Khan

Live performance, 12 December 1997 at the Queen Elizabeth Hall, Southbank Centre, London

Reviewed by Richard Whitehouse

What’s the story?

Toccata Classics fills a major gap in the Havergal Brian discography with this release of his opera The Cenci, given its first hearing 27 years ago by a notable roster of soloists with The Millennium Sinfonia conducted by James Kelleher, and accorded finely refurbished sound.

What’s the music like?

The third among the five operas which Brian completed, The Cenci emerged as the second of its composer’s seminal works inspired by Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822). While his ‘lyric drama’ on the first two books of Prometheus Unbound (1937-44) had set its text almost word for word, Brian was ruthless in adapting his ‘tragedy in five acts’ – the outcome being a rapid traversal of a drama whose themes of incest and parricide made it publicly unstageable in the UK until 1922, some 103 years after publication in Livorno where it had partly been written.

Two further operatic treatments emerged either side of that by Brian. Berthold Goldschmidt’s Beatrice Cenci (1949-50) won first prize in the Festival of Britain opera competition in 1951 but itself went unheard 1988 (ironically enough, in a concert performance at Queen Elizabeth Hall), and Alberto Ginastera’s Beatrix Cenci (1970-71) went unstaged in his native Argentina until as recently as 2015. Whereas both these operas centres on the heroine of Shelley’s play, Brian’s focusses more on its ensemble as to content with the emphasis shifting from father to daughter as it unfolds. Compared to the poised yet rather self-conscious lyricism favoured by Goldschmidt or the full-on expressionism of Ginastera, moreover, its often circumspect and sometimes oblique emotional demeanour renders Shelley’s drama from an intriguing remove.

Not its least fascination is the Preludio Tragico that, at 14 minutes, is less an overture than an overview of what ensues – akin to Beethoven’s Leonora No. 2 in its motivic intricacy and expressive substance – which would most likely warrant a balletic or cinematic treatment in the context of a staging. Perfectly feasible as a standalone item, this received its first hearing in 1976 and was recorded by Toccata Classics in 2009 (TOCC0113). Ably negotiated by his players, Kelleher’s lithely impulsive account accordingly sets the scene in unequivocal terms.

What follows are eight scenes which encapsulate this drama to compelling if at times reckless effect. The initial three scenes correspond to Shelley’s first act and culminate with the gauntly resplendent Banquet Scene, but Brian’s fourth scene goes straight to the play’s fourth act with the despairing exchanges of Beatrice and Lucrecia. The fifth scene finds daughter and mother in a plot to murder Count Cenci that soon unravels, then the last three scenes take in Shelley’s fifth act as fate intervenes with Beatrice, Lucretia and stepbrother Giacomo facing execution. Save for a crucial passage where the Papal Legate arrives to arrest Cenci, omission of which jarringly undermines continuity in the fifth scene, Brian’s handling of dramatic pacing leaves little to be desired – the one proviso being the excessive rapidity with which certain passages, notably several of Cenci’s, need to be sung that would have benefitted from a slight easing of tempo. Musically, this is typical of mature Brian in its quixotic interplay of moods within that context of fatalism mingled with defiance as few other composers have conveyed so tangibly.

Does it all work?

Very largely, owing to as fine a cast as could have been assembled. Helen Field is unfailingly eloquent and empathetic as Beatrice, with such as her remonstrations at the close of the fifth scene and spoken acceptance at that of the eighth among the highpoints of mid-20th century opera. David Wilson-Johnson brings the requisite cruelty but also a sadistic humour to Count Cenci, and Ingveldur Ýr Jónsdóttir is movingly uncomprehending as Lucretia. The secondary roles are expertly allotted, notably Justin Lavender’s scheming Orsino and stricken Bernardo. The Millennium Sinfonia responds to Brian’s powerful if often abrasive writing with alacrity under the assured guidance of James Kelleher, and if the sound does not make full use of the QEH’s ambience, its clarity and immediacy tease unexpected nuance from the orchestration.

This set comes with two booklets. One features the libretto devised by Brian, duly annotated to indicate omissions or amendments (yet a number of anomalies in this performance remain unaccounted for). The other features Shelley’s own preface to the first edition, with articles by Brian afficionados including John Pickard’s informative overview of the music and Kelleher’s thoughts on its performance. Charles Nicholl’s speculations as to the ‘real’ Beatrice Cenci are more suited to activities on a culture cruise than to Brian’s opera but are entertaining even so.

Is it recommended?

It is indeed. The Cenci is unlikely to receive further performances (let alone staging) any time soon, so this reading gives a persuasive account of its manifest strengths and relative failings. Kelleher is ‘‘formulating plans to return to conducting’’ and ought to be encouraged to do so.

Listen & Buy

You can listen to samples and explore purchase options on the Toccata Classics website Click on the names for more on conductor James Kelleher and to read more about the opera at the Havergal Brian Society website

Published post no.2,298 – Wednesday 11 September 2024