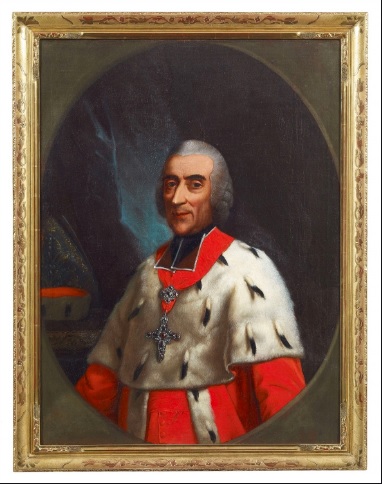

Beethoven, aged 13. This portrait in oils is said to be the earliest authenticated likeness of Beethoven – but Beethoven-Haus Bonn disputes this description, claiming it to be an unknown youth painted in the early 19th century.

Piano Concerto in E flat major WoO 4(1783-4, Beethoven aged 13)

Dedication not known

Duration 24′

Listen

Background and Critical Reception

Daniel Heartz tells the story of Beethoven’s first foray into the world of the concerto. Barely a teenager, ‘it was appropriate to the young composer’s status as a virtuoso of the keyboard that he should try his hand at writing a piano concerto.’

The work was incomplete however, with the orchestral part left unfinished beyond its two-piano reduction. The trip to Holland mentioned in the previous article on the Rondo in C major looks to have been the driving force behind this composition, for Heartz says that ‘Beethoven may have performed it in a concert at The Hague for which he was paid a large sum as a pianist, and at which Carl Stamitz also appeared as a viola soloist.’

As Jan Swafford notes, the work begins with a ‘flavour of hunting call-cum-march’, an ‘abiding topic in his future concerto first movements’. He calls it a ‘lively and eclectic piece that showed off his virtuosity’, while in his booklet notes to the DG complete Beethoven edition Barry Cooper notes its proximity in style to J.C. Bach rather than Mozart.

Thoughts

In Ronald Brautigam’s recording – where he made the orchestral arrangement – the horns are prominent in the opening salvo, which is reasonable to expect given the key of E flat major which will suit them. Then the piano takes over with an upbeat theme and some florid passagework. The music is fluently written, and follows the rules relatively closely in moving to the keys expected in the course of its development – B flat major, G minor, closely ‘related’ to the home key. The music is both charming and virtuosic.

For the slow movement Beethoven revisits a Larghetto direction (slow but not as slow as the ‘adagio’ tempo marking’) and writes music of an appealing delicacy and charm – undemanding but giving the soloist room to spread their wings a little.

For the finale Beethoven uses a Rondo form (presenting three themes in the sequence A – B – A – C – A – B – A) – a form he used for the last movement of each of his five published piano concertos. Despite the rigorous structure it again sounds very natural and the ‘A’ theme – which you hear from the start – is lightly playful, suggesting a less formal dance. The grace and charm of the third movement has a nice complement in the shape of a rustic ‘C’ theme where we briefly flirt with the minor key and the melody becomes more decorative. Only the ending is a bit strange, with a sudden cut-off point.

Recordings used

Ronald Brautigam (piano), Norrköpping Symphony Orchestra / Andrew Parrott (BIS)

Orchestra of Opera North / Howard Shelley (piano) (Chandos)

Ronald Brautigam gives a fine performance of the concerto, with attentive accompaniment from Andrew Parrott and the Norrköpping Symphony Orchestra. Howard Shelley’s version has a softer orchestration for the first theme of the piece which works really nicely. His playing follows suit, proving particularly effective in the second movement where his affection for Beethoven’s early work is clear.

Spotify links

Ronald Brautigam, Norrköping Symphony Orchestra / Andrew Parrott (tracks 1-3 of the link below)

Orchestra of Opera North / Howard Shelley (piano) (the fourth disc of an album containing all the Beethoven works for piano and orchestra)

You can chart the Arcana Beethoven playlist as it grows, with one recommended version of each piece we listen to. Catch up here!

Also written in 1783 Abel 6 Symphonies Op.17

Next up Piano Concerto in E flat major WoO 4