Miller La Donna (2021) [UK premiere]

Britten Violin Concerto in D minor Op.15 (1938-9)

Beethoven Symphony no.6 in F major Op.68 ‘Pastoral’ (1807-08)

James Ehnes (violin), City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra / Finnegan Downie Dear (above)

Symphony Hall, Birmingham

Wednesday 6 October 2021

Written by Richard Whitehouse; Picture of Frankie Downie Dear (c) Frank Bloedhorn

Tonight’s concert by the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra saw a first appearance with British conductor Finnegan Downie Dear, winner of the 2020 Mahler Competition in Bamberg, and a first hearing in the UK for an orchestral piece by the Canadian composer Cassandra Miller.

Currently based in London, where she is Professor of Composition at the Guildhall, Miller’s output has often drawn on pre-existing sources as are then integrated into the work at hand. Such is the case with La Donna, premiered at Barcelona earlier this year, where a group of Genoese male voices singing La Partenza da Parigi (as recorded by the redoubtable Alan Lomax in 1954) is channelled into music of intensive polyphonic activity and topped by a falsetto melodic line – the eponymous La donna. This builds to an apex as intricate in its texture as it is immediate in expression, then gradually subsides in a resonance of suffused elation. Such was the impression left by this performance, Downie Dear drawing sustained amplitude from relatively modest forces in a visceral demonstration of tension and release.

A time there was when Britten’s Violin Concerto enjoyed only a modest presence in British concert halls, though recent years have seen it taken up by leading soloists from around the world. Its edgy yet intense lyricism has a persuasive exponent in James Ehnes (above), who brought out the restless emotion of the initial Moderato – the five-note motto underlining the context of war and unrest from which it emerged. The Vivace’s rhythmic velocity and sardonic tone were no less evident, a tensile reading of the cadenza pointing up its thematic function and leading inevitably into the final Passacaglia. After a superbly shaped orchestral introduction, Ehnes characterized its variations with mounting intensity to a powerfully wrought climax – the final pages exuding a fatalistic eloquence no less affecting now than eight decades ago.

Perhaps this music’s rapt equivocation explains why it has often been programmed in recent seasons with Beethoven’s Pastoral. While by no means revelatory, the present account gave a good indication of Downie Dear’s abilities – not least his emphasis on rhythmic articulation during what was a relatively swift traversal of the opening Allegro, along with his fastidious attention to dynamics as brought the requisite focus and lucidity to the Scene by the Brook with its warmly enveloping string textures and its bird-calls deftly inflected towards the close.

The final three movements unfolded in much the same vein – the peasants lithe if arguably a little too well-behaved in their merrymaking and the thunderstorm forceful if not electrifying in response, though with a seamless diminuendo of volume and energy going into the finale. Without drawing the ultimate gravitas from its interplay of rondo and variation procedures, Downie Dear guided it surely and attentively to a ruminative coda – Beethoven transcending the incipient era of musical romanticism through the (deliberate) absence of any defining ego.

This evening’s programme is repeated tomorrow afternoon – with the Miller being replaced by Mozart’s Idomeneo overture – while the CBSO returns next week for Rossini, Berlioz, and Prokofiev under François Leleux, along with Baiba Skride in Mozart’s Fifth Violin Concerto.

Further information on the CBSO’s current season can be found at the orchestra’s website. For more on Cassandra Miller, click here – and for more information on Finnegan Downie Dear, head to the conductor’s website

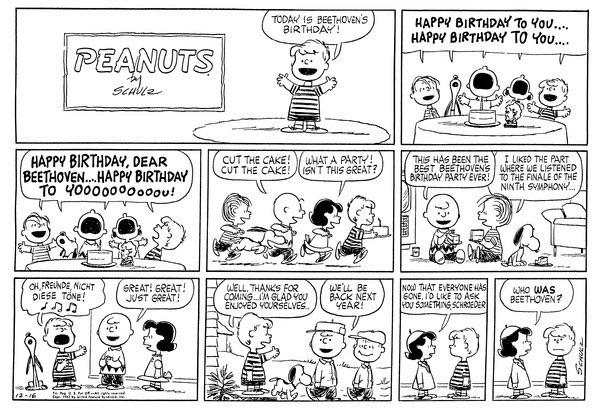

Peanuts comic strip, drawn by Charles M. Schulz (c)PNTS

Peanuts comic strip, drawn by Charles M. Schulz (c)PNTS