Maria Casentini, Beethoven’s prima ballerina for The Creatures of Prometheus. Used courtesy of Beethoven-Haus Bonn

Die Geschöpfe des Prometheus (The Creatures of Prometheus) Op.43 for orchestra (1801, Beethoven aged 30)

Dedication Salvatore Viganò & Empress Maria Theresa

Duration 60′

Music and reconstruction of the plot (from Wikipedia)

Act 1

Introduction

Poco adagio

Adagio – allegro con brio

Minuetto

Act 2

Maestoso – Andante

Adagio – Andante quasi allegretto

Un poco adagio – Allegro

Allegro con brio – Presto

Adagio – Allegro molto

Pastorale

Andante

Maestoso (also known as “Solo di Gioia” for solo dancer Gaetano Gioia) – Procession of Silenus

Allegro – Comodo – Dance of Pan and two fauns or nymphs

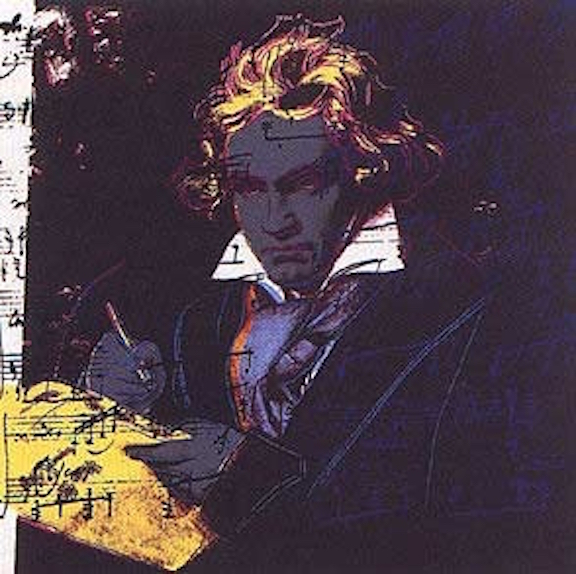

Andante – Adagio (also known as Solo della Casentini, written for Beethoven’s prima ballerina, Maria Casentini)

Andantino – Adagio (also known as Solo di Viganó)

Finale- Wedding

Listen

Background and Critical Reception

Ballet had been a central feature of entertainment in Vienna’s court theatres for several generations prior to Beethoven’s arrival, and after a fallow period under Joseph II, Leopold II restored it to a higher standing in the 1790s. Beethoven had just one encounter with the stage in Bonn, his music for the Ritterballet, but as Daniel Heartz points out many of the piano variations he wrote in Vienna were based on dances or arias, showing he was keeping abreast of new works for the stage.

The celebrated choreographer Salavtore Viganò was asked to premiere a new work each year in Vienna from 1799, and in 1801 he chose to focus on the story of Prometheus. With the intention to honour Empress Marie Therese, Beethoven was invited to write the music, and the hour-long score occupied him up to the premiere in the Burgtheater on 28 March 1801.

Anthony Burton, writing in the Deutsche Grammophon Complete Beethoven, remarks that ‘The Creatures of Prometheus is a work of unusual interests in two respects. It consists of over an hour of mature Beethoven…which is virtually unknown apart from a short overture and one tune in the finale. And it is one of only two extended ballet scores by major composers of the Classical period (the other is Gluck’s Don Juan) to have survived intact. After its first performance the piece became wildly popular, receiving another 28 performances before the end of the following year.

Summarising the plot, he writes, ‘The demigod Prometheus creates two human figures out of clay and brings them to life with the aid of fire stolen from heaven. Finding them lacking in any emotion, he leads them to Parnassus, where they are instructed in the arts by Apollo, Bacchus and the Muses, and through the power of harmony made susceptible to all the passions of human life.’

Heartz describes the structure of the ballet as a ‘heroic-allegorical’ story with the heroism in Act 1 and the allegorical work in Act II, a much longer structure’. The overture, with its close links to the Symphony no.1 in C major, is often performed separately as a concert-opener. Act II is described as ‘more pageant than action ballet’.

Heartz picks out three numbers for special attention. No.8 is described as ‘an impressive rondo in martial style’, no.10 ‘a lovely Pastorale’, and no.16 ‘the great Finale’, where Beethoven writes a theme later used in his Eroica Variations Op.35, and the finale of the Eroica symphony. No.14 in F is the big solo for the celebrated Signora Casentini, playing the first woman created.’

Anthony Burton’s conclusion is striking. ‘Prometheus caught and enhanced the dramatic fire of which Beethoven was capable. It emboldened him to attempt more daring orchestral feats in Symphony no.2. Experience in theatre helped him when he returned to the dramatic stage with his Leonore in subsequent years.

With all that said, audiences were disappointed, in spite of Beethoven’s prowess as a composer. As he wrote just three weeks after the premiere, ‘I have made a ballet, but the ballet master did not make the very best of his end of the job’.

Thoughts

Most concert-goers encounter just five minutes of Beethoven’s music for The Creatures of Prometheus, through the Overture. It is often chosen as an opening piece by orchestras because of its abrupt start, a chord hewn from the rock face. Like the beginning of the first symphony it is a C major chord with an added seventh (B flat) but this time the added note is at the bottom of the texture. The sharp attack no doubt stifles conversation among even the most disruptive audience members! Beethoven’s expert use of silence around the first few chords heightens the drama.

If the Overture is the only part of the ballet you have heard, then you have been missing out. The Creatures of Prometheus might not be a forsaken masterpiece, but it has a lot of good tunes, imaginative orchestration and some very positive music. The relative lack of plot does play a part at times, meaning there is not quite as much contrast in the music of Act 2 as there might have been, but Beethoven’s writing more than compensates.

The orchestration feels heavier than the first symphony, both in the overture and in the bright and breezy section where the statues come to life. The harp playing of Amphion is a striking beginning to the fifth number, which also has a striking cello solo (Orpheus) whose cadenza is followed by a soft-hearted theme as the creatures are presented to Apollo.

There is an impressive heft to the section where the two humans are taught martial arts, while the Pastorale is rather lovely. The prima ballerina solo is elegant and beautifully scored, with solos for basset horn and oboe. The penultimate number begins in subdued fashion but breaks out into a vigorous exchange. Finally we turn to one of Beethoven’s favourite keys, E flat major, for the wedding and celebration of Prometheus’ mission. The important theme ends the ballet in celebratory mood, with a spring in the step and some bracing orchestral figures.

A highly enjoyable hour in Beethoven’s company, then – and an energising one too.

Spotify playlist and Recordings used

Orchestra of the 18th Century / Frans Brüggen (Philips)

Chamber Orchestra of Europe / Nikolaus Harnoncourt

Orpheus Chamber Orchestra (Deutsche Grammophon)

Freiburger Barockorchester / Gottfried von der Goltz (Harmonia Mundi)

After the opening chords ricochet, the sound of the Freiburger Barockorchester is unexpectedly rich in the lower end, before a headlong rush through the first Allegro. Their approach is a vigorous one, and highly enjoyable in the faster music where a gutsy orchestral sound is revealed.

Frans Brüggen conducts another ‘period instrument’ version with real panache, his Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century not quite as bombastic as their counterparts from Freiburg but giving a classy interpretation nonetheless. Nikolaus Harnoncourt conducts a version with plenty of character from the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, while the conductor-less Orpheus Chamber Orchestra impress with their control and depth, if not quite as much evident excitement as the period versions.

To listen to clips from the recording from the Scottih Chamber Orchestra conducted by Sir Charles Mackerras on Hyperion, head to their website

You can chart the Arcana Beethoven playlist as it grows, with one recommended version of each piece we listen to. Catch up here!

Also written in 1801 Haydn The Spirit’s Song, Hob.XXVIa:41

Next up Sonata for piano and violin no.4 in A minor Op.23