Morning on the Riesengebringe, by Caspar David Friedrich (1810)

Morning on the Riesengebringe, by Caspar David Friedrich (1810)

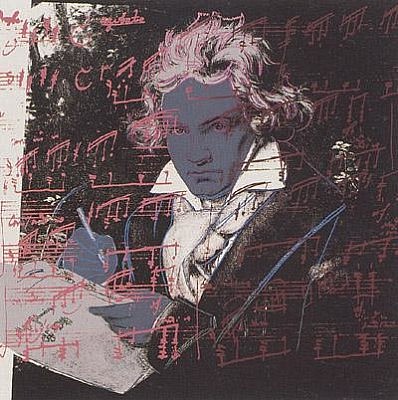

String Quartet in G major Op.18/2 (1798-1800, Beethoven aged 29)

Dedication Count Johann Georg von Browne

Duration 25′

1. Allegro

2. Adagio cantabile – Allegro – Tempo I

3. Scherzo: Allegro

4. Allegro molto, quasi presto

Listen

written by Ben Hogwood

Background and Critical Reception

‘The jester of the set’, says Daniel Heartz of the second of Beethoven’s first published string quartets. Op.18/2 was actually written third, but is carefully placed by the composer to keep a satisfactory flow between the works. In Germany it acquired the occasional nickname ‘Komplientierquartett’, for what Ludwig Finscher calls the ‘graceful principal theme’. The nickname reflects on the quartet too, ‘not merely to compliment but to greet with formal respect and ceremony’.

Commentators identify more links with the past in this work than the forward looking first – yet the links do not mean the work itself is unadventurous. Finscher writes of how the first movement ‘reaches back beyond Haydn to the preclassical realm, but technically, in its almost parodic succession of two-bar groups and tiny, conventional motives, it is a dazzling tour de force, building on the achievements of the Haydn quartet style and simultaneously providing an ironic comment on them’.

Heartz draws close links with Haydn’s String Quartet Op.33/2, also in G major – and gives several examples on how the first and second movements draw on Haydnesque qualities. Finscher extends his observations, concluding that ‘in artistic skill of that order the work is also a celebration of the level of musical culture in Vienna around 1800’.

Thoughts

It is true that the second of Op.18 is very different from the first – but in a complementary way. The mood is amiable and often comedic, the first violin taking the lead in a cheery second theme, where it ascends to the heights like a bird. Some of the harmonic movements are adventurous in the development, showing that if Beethoven is influenced by Haydn he is channelling the composer’s inventive powers too. The viola and cello take the lead in a striking build to a recap of the main theme.

There are more powers of invention in the slow movement, where tender moments give way to an unexpected, capricious section in the middle. The scherzo third movement is another advance on the traditional minuet, light in mood before cutting to an elusive trio section.

At this point it suddenly feels like the work is finishing, but then Beethoven surges forward with an assertive finale, led off by the cello and featuring busy interactions between the four instruments.

Beethoven has fun with this piece, and given the right performance the listener will do too. The Haydn influences are welcome and well-managed, because the quartet never sounds derivative, and its frequent but subtle inventions keep the listener on their toes. A joy from start to finish.

Recordings used and Spotify links

Quatuor Mosaïques (Andrea Bischof, Erich Höbarth (violins), Anita Mitterer (viola), Christophe Coin (cello)

Melos Quartet (Wilhelm Melcher and Gerhard Voss (violins), Hermann Voss (viola), Peter Buck (cello) (Deutsche Grammophon)

Borodin String Quartet (Ruben Aharonian, Andrei Abramenkov (violins), Igor Naidin (viola), Valentin Berlinsky (cello) (Chandos)

Takács Quartet (Edward Dusinberre, Károly Schranz (violins), Roger Tapping (viola), Andras Fejér (Decca)

Jerusalem Quartet (Alexander Pavlovsky, Sergei Bresler (violins), Ori Kam (viola), Kyril Zlotnikov (cello) (Harmonia Mundi)

Tokyo String Quartet (Peter Oundjian, Kikuei Ikeda (violins), Kazuhide Isomura (viola), Sadao Harada (cello) (BMG)

Végh Quartet (Sándor Végh, Sándor Zöldy (violins), Georges Janzer (viola) & Paul Szabo (cello) (Valois)

The Végh Quartet give a delightful account of this piece, light on their feet and pretty quick, but still with plenty of room for their phrasing. The Tákacs Quartet are often brisk, but similarly enjoyable, while the Quatuor Mosaïques are slower and emphasise the graceful interplay between the quartet. Finally the Tokyo String Quartet are nicely poised and enjoy Beethoven’s flights.

You can chart the Arcana Beethoven playlist as it grows, with one recommended version of each piece we listen to. Catch up here!

Also written in 1800 Krommer String Quartet in A major Op.18/2

Next up String Quartet in D major Op.18/3