George Lloyd

Piano Concerto no.1 ‘Scapegoat’ (1962-3)

Piano Concerto no.2 (1963-4, orch. 1968)

Piano Concerto no.3 (1967-8)

Martin Roscoe (piano), BBC Philharmonic Orchestra / George Lloyd

Piano Concerto no.4 (1970, orch. 1983)

Kathryn Stott (piano), London Symphony Orchestra / George Lloyd

Lyrita SRCD.2421 [two discs, 73’49” and 70’17”]

Producers Ben Turner (1&2), Chris Webster (3), Howard Devon (4)

Engineers Harold Barnes (1&2), Tony Faulkner

Recorded 9 & 10 February 1984 at Henry Wood Hall, London (Piano Concerto no.4), 25 & 26 September 1988 (Piano Concerto no.3) and 20 & 21 October 1990 at Studio 7, New Broadcasting House, Manchester (Piano Concertos 1 & 2)

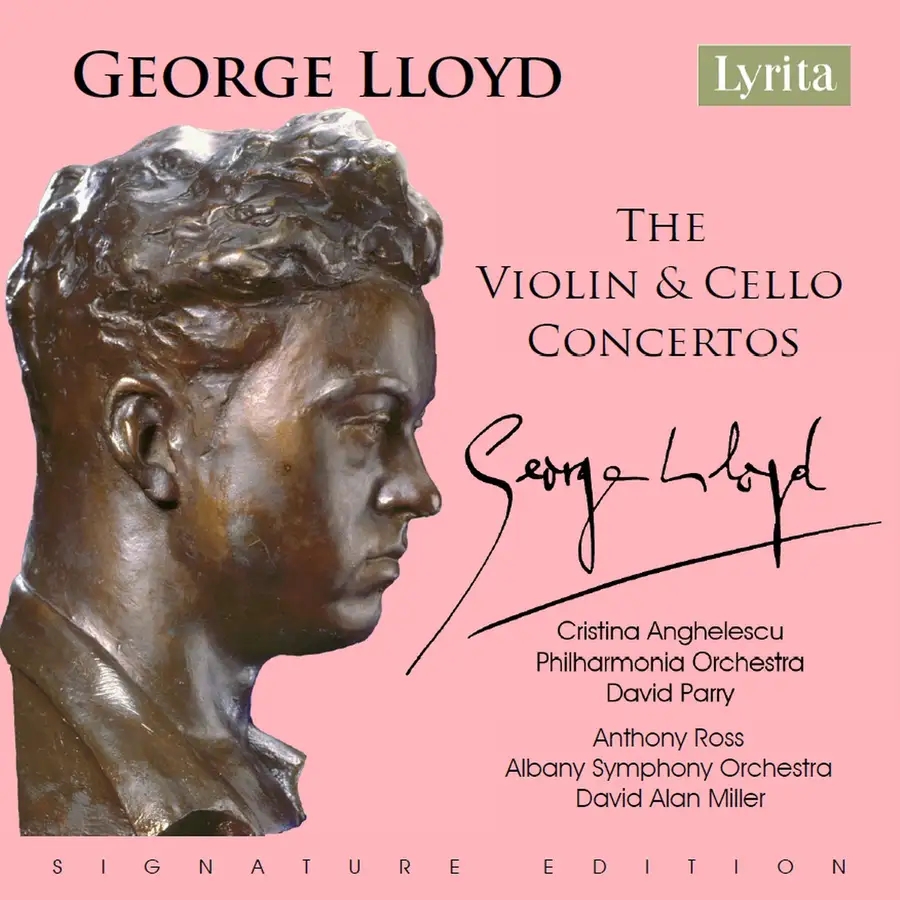

George Lloyd

Violin Concertos no.1 (1970)

Violin Concerto no.2 (1977)

Cristina Anghelescu (violin), Philharmonia Orchestra / David Parry

Cello Concerto (1997)

Anthony Ross (cello), Albany Symphony Orchestra / David Alan Miller

Lyrita SRCD.2422 [two discs, 64’37” and 29’40”]

Producers Ben Turner (Violin Concertos), Gregory Squires (Cello Concerto)

Engineers Phil Hobbs (Violin Concertos), Gregory Squires (Cello Concerto)

29 June to 3 July 1998 at Henry Wood Hall, London (Violin Concertos), 22 April 2001 at Troy Savings Bank Music Hall, Troy, NY (Cello Concerto)

Reviewed by Richard Whitehouse

What’s the story?

Lyrita continues its ‘Signature Edition’ of George Lloyd recordings (originally for the Albany label) with two volumes respectively devoted to his concertos for piano and string instruments – all of them being played by soloists either conducted by or who worked with this composer.

What’s the music like?

His previous output having been dominated by the genres of opera, or symphony, Lloyd came belatedly to the concerto. An able violinist in his youth (and taught for several years by Albert Sammons), he had resisted his wife’s predilection for the piano until the early 1960s when he wrote four such works in barely eight years, followed at lengthier intervals by two for violin then one for cello. No less characteristic of their composer, these constitute a significant part of his development from a time when his music was still largely unknown to the wider public.

Hearing the young John Ogdon galvanized Lloyd into writing for the piano, with Scapegoat his striking first attempt at a concerto and his most performed work since before the Second World War – its 1964 premiere in Liverpool, Charles Groves conducting, soon followed with hearings in Bournemouth, Glasgow, Berlin then a BBC broadcast in 1969. A pity that Ogdon never recorded a piece ideally suited to his temperament – its single movement duly taking in elements of the soulful and sardonic in a close-knit structure with Lloyd’s motivic thinking at its most resourceful. Ominous, aggressive, ultimately fatalistic, this is one of the composer’s most cohesive works and urgently warrants revival. Lloyd had enough ideas for its successor but, for reasons unstated, Ogdon never played the Second Piano Concerto that went unheard until 1984. Its single movement yields a distinct progression from trenchant ‘first movement’ via lively ‘scherzo’ then, after an elaborate cadenza, threnodic ‘slow movement’ and resolute ‘finale’ as brings the whole structure into focus while not precluding a tangible equivocation.

Not to be deterred, Lloyd pressed on with his Third Piano Concerto. Brahmsian in scale, its three movements eschew both symphonic density and virtuosic flamboyance – whether in an opening Furioso whose relative brevity belies its wealth of incident, a Lento which sustains its expansive length through imaginative interplay between soloist and orchestra and with a keen sense of atmosphere, then final Vivace that pointedly fights shy of any grand peroration as it heads to a decisive if hardly affirmative close. The piece remained unheard until 1988, whereas the Fourth Piano Concerto had made it to the Royal Festival Hall four years earlier as part of the artistically lauded while commercially disastrous Great British Music Festival. The three movements find Lloyd attempting to banish painful memories in favour of a more relaxed but still restive discourse – hence the poignancy behind the geniality of the opening Allegro, suffused pathos of a central Larghetto that is its undoubted highlight, then animated final Vivace whose spirited ending is offset by the soulful Lento interlude which precedes it.

Hardly had Lloyd finished this last of his piano concertos when he wrote the first of his violin concertos. As the booklet note suggests, its scoring for woodwind and brass has the urbanity of a divertimento or serenade – which holds good for the sanguine opening movement and its plaintive successor, whose cor anglais melody is one of Lloyd’s most potent ideas, but less so for a rather prolix eliding of scherzo and finale. More convincing overall is the Second Violin Concerto, its resonant scoring for strings and obliquely spiritual programme demonstrably to the fore in the initial Lento with its plangent chorale. After an impulsive scherzo and eloquent slow movement, the final Vivace reaches a close whose joyfulness is never contrived. A fine piece, but the Cello Concerto is one of Lloyd’s finest. His penultimate work feels valedictory in tone, its seven continuous sections outlining a four-movement sequence whose clarity of expression is abetted by its scoring for modest forces, and whose subtle range of mood makes the final evanescence more affecting. A professional performance in the UK is well overdue.

Does it all work?

Pretty much. Those aspects of the piano concertos which do not quite succeed are due more to recordings which, scrupulously prepared and lucidly rendered, lack a degree of intensity in their execution. That 1969 broadcast of Scapegoat confirms what is lacking here, but Martin Roscoe is never less than attentive in the first three concertos and Kathryn Stott brings a deft touch to the fourth. Cristina Anghelescu plays with dexterity and no mean insight in the violin concertos, while Anthony Ross is fully attuned to the fatalistic restraint of the Cello Concerto.

Is it recommended?

Yes, but listeners unfamiliar with Lloyd’s symphonies and choral works should hear these in the first instance. Lyrita’s presentation, with objectively enthusiastic notes by Paul Conway, is up to its customary standards and those who are acquiring this series should be well satisfied.

Listen & Buy

For further information visit the dedicated George Lloyd page at the Nimbus website

Published post no.2,222 – Thursday 27 June 2024