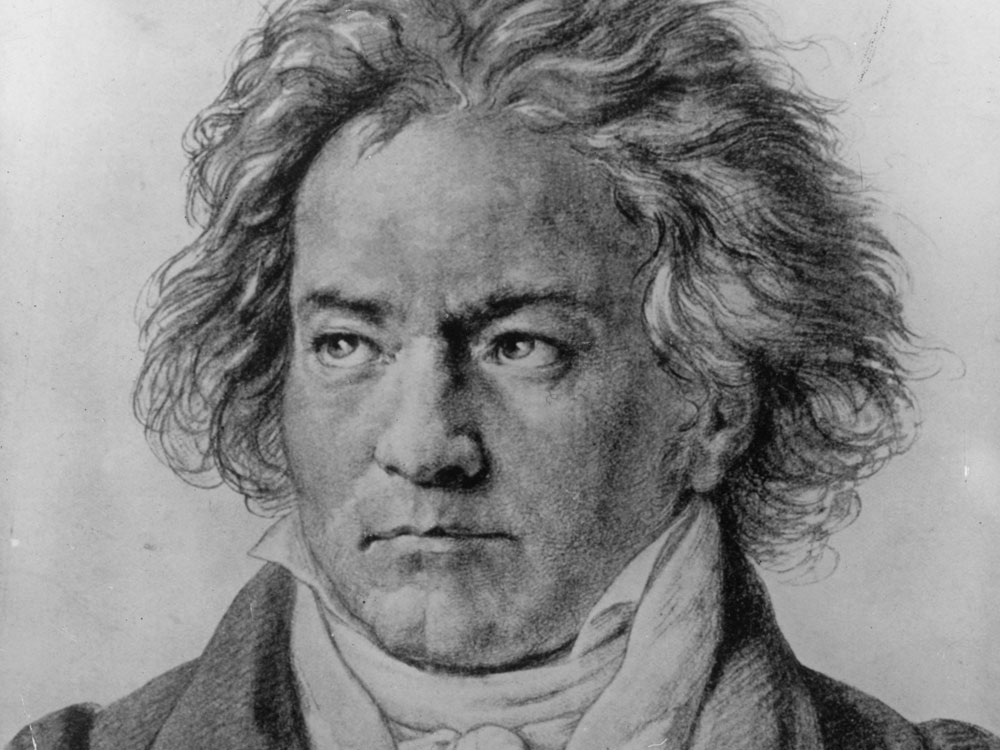

Arcana has an audience with cellist Jennifer Kloetzel, on Zoom from Nebraska. Kloetzel and pianist Robert Koenig have been spending a good deal of time with the music of Beethoven, and the fruits of their labours have just been released to critical acclaim by Avie. Beethoven: The Conquering Hero is a trible album bringing together all of the composer’s works for cello and piano. It is the completion of a long-held dream for the cellist, whose enthusiasm for her project bubbles over from the off.

“I’m still celebrating!” she says of Beethoven 250, the composer’s bicentenary having been cruelly cut up by the pandemic. “This album was supposed to be released right after the 250, but we got waylaid by the pandemic, and couldn’t get into the studio to finish. I don’t think Beethoven would care that we were late though!”

Kloetzel’s route to the Beethoven sonatas came by way of the complete string quartets, which she recorded as cellist of the Cypress String Quartet (below). “We recorded the late quartets first”, she remembers, “and then, many years later, we did the middles, and then, finally, just a quick two years before we disbanded, we did the earlies. It was fascinating to go backwards through his string quartet writing. If I had started the other way I would have thought the Op.18 quartets sound Mozartian, but seeing them from that way I saw everything that was going to happen later early on. It’s like when you look at a baby picture of somebody, it’s hard to tell what they’re going to look like as someone older, but later when you look back, you see them.”

She thought carefully of the ordering on the new cello release. “I didn’t record them straight from beginning to end, but I decided to put them in that listening order. If someone wants to sit down for three hours, they can go from 1796 to 1815, and have the experience of his writing for cello and piano with that little fun arrangement of the Horn Sonata thrown in. The thing that made me pause when I was doing that was the third, fourth and fifth sonatas, which are considered the biggest ones, and you have to wait for the entire third disc.”

Kloetzel includes the variations Beethoven wrote for piano and cello, and the ‘Conquering Hero’ title of the disc takes its name from the source of the first set of variations – Handel’s chorus See The Conquering Hero Comes, from the oratorio Judas Maccabaeus. “I had a lot of pushback on that title from people”, she says. “It’s more about Beethoven being the conquering hero, and what he conquered and became – the deafness, the lack of love. Everything after the battle with his nephew, and the fact he kept turning to music to write and express himself. That’s why I decided on the title, because in my mind, he is a conquering hero.”

Throughout the three discs, Kloetzel and Koenig (below) give off a pure enjoyment of Beethoven’s work. “I love the way things are put together, and I was reminded as I was doing this project, how clever Beethoven is. One of my favourite traits in all humans is cleverness, and Beethoven has it in spades. He’ll do something where the cello is in a certain range, and he’ll make sure that the piano parts are really not anywhere near that. When I was studying it for the recording, I would look to see where the piano part was. It is really interesting and thoughtful orchestration, carefully done. There is something perfect about that endless cleverness, and the dialogue back and forth. I was telling someone the other day that I was working on the Handel Variations, and it cracked me up that Beethoven doesn’t even give the cello the main theme until the tenth variation! Even then the piano has it in canon, low in the left hand.”

The sonatas are laced with feeling. “The G minor sonata, Op.5 no.2, has some serious drama, and I hear the Op.69 A major sonata with a degree of wistfulness and sadness, which I think brings something a little different to my interpretation, that it’s not all conquering joy. The music is so varied, too – he never does anything twice! When I was in college, I wrote a paper about the last two sonatas and how they are the turning point. They contain the hallmarks, the trills, the canons and the fugues.”

She agrees that the opening of the first of Beethoven’s two Op.102 sonatas feels like the opening of a new door. “I think so. One of the things that I find fascinating is that with both the third and fourth sonatas, he begins with solo cello. I read that Beethoven said, “Art demands of us that we never stand still.” And so he never does that same thing twice. In this case, he kind of does except it’s a really different type of melody, but it definitely is a signpost towards equal partnerships. The earlier works have a bit more weight to the piano, but of course it would have been him playing it! For almost all of that early stuff, up until about 1802, that’s the case, but after that, it’s not implied anymore. Part of the reason I find this music endlessly fascinating is that it’s always surprising, even to me, or in the way the contrast and the content is set up. If you follow the markings on his music, you find that buried treasure. So many people add in crescendos and the like, but I think he knew what he was doing!”

Kloetzel also follows Beethoven’s markings for repeats, whereby sections of the sonata movements are heard for the second time. “I included every repeat in all of these works, as I am a believer in the form, and I think that he knew what he was doing. In the G minor Sonata, the first movement has a double repeat. Now I know it makes the movement 21 minutes long, but I think it’s fascinating. I never performed it that way, but as I was studying it for the recording, I realised that he meant this!”

She confesses to playing the Second Sonata when just eight years old, which begs the question – at what age did Kloetzel actually start playing the cello? “I started at age six”, she says. “My mother is an opera singer, and in my family, I’m one of four children. You had to play piano and one other instrument. When I was five I heard the sound of the cello and I said, “I want to play”. My parents were like, “You’re too young, too little.” I begged for an entire year to play the cello, and so they finally rented a half-sized cello. After about six weeks, I get my first recital, which we have a tape of, by the way!” I did my own variations on Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star, but I couldn’t quite tune the cello, so it sounds a little modern! A few weeks later my teacher came to my mother and said, “She’s scaring me, she’s learning so fast. Please take her to Baltimore and find a teacher for her there. That’s where I did 10 years in the pre-college there, before going to the Juilliard School.”

Kloetzel and Koenig both met at Juilliard. “Bob and I were there around the same time. He was one of the collaborative pianists, playing mostly with violins. Then six years ago when I got the job at University of California in Santa Barbara, he was the person to reach out to me and say, “Hey, we have a job opening. I see your quartet is just ending.” So I applied, and as part of the audition we actually played the Third Sonata together, because he played with me for the audition. That’s six years ago, and we started playing together right away. We played the G minor Sonata just a few months later, and my mother said how she was blown away by the two of us, it was like ‘hand in glove’. I think the two of us come from a similar background of making chamber music and really listening and responding, which makes it a very special partnership. I just knew he was the person to do this with me!”

Kloetzel has two points of reference for running through Beethoven’s output from early to late – the string quartets and now the sonatas for piano and cello. Is there a noticeable development in his writing for cello? “Let’s look at Opus 59 no.1”, she says a little unexpectedly, turning to the first of the Razumovsky Quartets. “A middle period work, one of my favourite quartets – it’s such a cello quartet, with the Russian theme. It’s like the Op.69 sonata, we’re right in that same middle, heroic period where he’s using all the voices equally. When we get to the later quartets, some of the cello parts are extremely high. When we get to Op.132 there’s a whole passage where the cello is way up high, soaring in octaves with the first violin, versus Op.131 where it’s very low.”

Mention of Beethoven’s Op.131 quartet, in C# minor no less, prompts a discussion on his use of keys. “It is fiendishly difficult, outrageous!”, Kloetzel agrees. “I remember really studying the key relationships, and how many he had written in each. F major is important, with three works, and E flat major too. I don’t see that as much in the cello sonatas. My friend Will Meredith, who wrote the booklet notes, he has given lectures on what keys mean to Beethoven. That’s like the language of flowers! His point though was that these things mattered. E flat was the heroic key – and you think of Op.127.”

Jennifer has a sudden realisation. “You know what I need to do next, right? The piano trios!” It would be a wholly logical step. “I have played them all, and the string trios too! We’ll see though. Stay tuned!”

Speaking from my own perspective as a part time cellist, I am curious to find out the technical demands as the cycle of cello sonatas progresses. “I don’t find they are as demanding as the quartets because of the length of the pieces”, she says. “With the quartets you can sometimes feel like you are about to climb a mountain when you start the piece. When you have a great pianist in the cello sonatas, you don’t have to fight to get your sound out – and that’s partly Beethoven’s writing. The hardest thing in a way is making sure all the ranges make sense. I read once that Beethoven didn’t think the cello could really be a solo instrument, because it couldn’t cut through. That is fascinating to me given they were playing with a fortepiano.”

Kloetzel is convinced that Beethoven knew the right people – particularly two cellists he met at an opportune time. “I think when he met the Duport brothers, in the Prussian court, that changed his opinion. I think we have them to thank for this body of work, and with the Mozart Prussian Quartets, freeing up the cello a little bit. In between the Duport brothers and Antonin Kraft, Beethoven heard very good cellists and knew what was possible. Interestingly we don’t have a fully-fledged slow movement in the sonatas, or the Triple Concerto. It’s a very short slow movement, and he puts the cello very high, like a violin. The Fifth Sonata has the closest thing to a slow movement, it spins and then goes into the fugue. The arc of that work is difficult, because it’s a short first movement and then you have to make it work. With the fugue, I’ve heard it played wildly fast. For my masters recital at Juilliard, I did all five sonatas on one programme, with two intermissions. It was such a great journey.”

Kloetzel has received advice on the sonatas from a close friend, Steven Isserlis, who has himself recorded the sonatas. “I adore him”, she says warmly. “He’s crazy and wonderful. He gave a class to my students a couple of years ago, and we reconnected after. I met him a while back, and he gave me a very difficult lesson on the fourth sonata many years ago, when I was a student living in Prague and he came through. Boy did he read me the riot act, for not doing my homework better – but out of that was born a friendship, so that was wonderful!”

Kloetzel and Koenig’s new recording complement Isserlis and Robert Levin, on the fortepiano, rather nicely. “I purposely didn’t listen to his recording of the Horn Sonata before ours”, says Jennifer, “as I didn’t want to be influenced by it. It’s hard when you’re preparing for a big project like this. I have multiple versions of the pieces, and favourite versions for sure, but one is elegant, one is passionate, one is exciting.” As to the piano, she says, “You realise how much Beethoven was playing with textures in the five sonatas”. The Horn Sonata is rather different. “There are more long lines within the cello / horn part, and moments where it’s like ‘No, he didn’t write anything like that for the cello. That is why I loved including it. There is a version of the Kreutzer Sonata played on cello, but I’m not so sure! It’s in a different key, and Bob was not sure about the piano part either. When I was trying to put this together I wanted it to be what Beethoven himself wrote”.

Although Beethoven is a huge part of Kloetzel’s work, especially recently, so too is contemporary music. It is clearly important for her to manage a balance between the different established and new classical works. “Absolutely, because in a way we’re only playing older music. We’re historians, right? We’re putting a fresh look at a moment in history, so I feel it is very important to look at the music of today, so that we not only continue to start but when people look back, they see what’s being written today. I also I have a whole passion of finding what I like to call the ‘living Beethovens’, composers whose music is interesting, thoughtful and clever – all the elements I love in Beethoven. Only yesterday I was on the phone with a composer who’s writing a Cello Concerto for me, and she’s just at the very beginning of writing so we were talking about ideas. She likes to have inspiration from something I’m thinking about, so it becomes a personal thing. I definitely think it’s important to play, and then not only to premiere works, but to champion them, so they get recorded.”

This approach has stayed with her. “When I was in the quartet, we had a whole process for choosing composers to commission which involved three of us not knowing where the music had come from. We would listen to the pieces on a playlist, and had a voting system to give our verdict, and then we would find out the composer. We called it ‘blind listening’ and it was great; it was about listening to the core of the music.”

“Just like I get obsessed with Beethoven I get obsessed with new music too, and the same thing happened with the string quartet he himself was writing for, the Schuppanzigh Quartet! Over the pandemic I was of course playing a lot of Bach, because I could, and that was a part of what kept me going when all the concerts went away. It was difficult, when what you are destined to do is gone, and live streaming was not the same. I said to myself “If nothing else, let’s play a little bit of Bach!” I made sure I played it every day, and I started to craft a project where I was commissioning companion pieces for each of the suites. I have five of the commissioned works so far. I went to my ‘go tos’ first but then I wanted to go further afield. That’s the old and the new again.”

She elaborates on the composers writing alongside the Bach. “There is Elena Ruehr, who wrote with the First Suite, and then a French composer Philippe Berson, he is amazing. He wrote a piece titled Sarabande for the Second Suite. For the Third Suite I turned to the very first composer I commissioned for the quartet, Dan Coleman, who was a colleague of mine at Juilliard and lives in Arizona. For lives in Arizona, and then for the fourth a colleague of mine from Santa Barbara, Sarah Gibson, a young female composer and pianist, I love the piece she wrote! The Fifth Suite is proving a little difficult, that’s the one I’m still waiting for, the person I wanted to do it was just too busy. I’m going to give that a little space, but then for the Sixth Suite I commissioned Aaron Clay, an African-American bass player from Virginia who is a very fine composer. Four of those are unperformed, and I hope not too much time goes by before they are.

There are other pieces that have been postponed. “There is a concerto by Joel Friedman that was supposed to be premiered during 2020 but has been postponed for another year or so. It is a Double Concerto, Inferno, for viola and cello – based on Dante’s Inferno. It has a political theme of what was happening, you know, in our country there for a while. It’s electrified, and we have to do all sorts of insane things – there’s a whole Skrillex effect I have to do. I’ve spent a lot of time figuring out pedals, with delay and looping. I’m excited about this piece, and art demands of us that we never stand still! There are too many things I would like to do but not enough hours in the day.”

You can listen to Jennifer Kloetzel and Robert Koenig’s Beethoven: The Conquering Hero at the Avie Records website where you can also explore purchase options.