Members of Birmingham Contemporary Music Group [Oliver Janes (clarinet), Ryan Linham (trumpet), Colette Overdijk (violin), Julian Warburton (percussion), Amelie Thomas (trumpet)]

Oram Counting Steps – first version (2020)*

Murail Les Ruines circulaires (2006)

Ma Xiao-Qing Back to the Beginning (2020)*

del Avellanal Carreño speak, sing… (2020)*

Donghoon Shin Couplet (2020)*

Howard R (2021)*

Reich New York Counterpoint (1985)

Birtwistle The Message (2008)

Oram Counting Steps – second version (2020)*

[Works indicated * received their live premieres]

CBSO Centre, Birmingham

Tuesday 15 June 2021

Written by Richard Whitehouse

It may have been unable to present live events during the past 15 months, but Birmingham Contemporary Music Group has not been inactive – commissioning a series of pieces from composers around the world for performance online as part of its Soliloquies & Dialogues project. Having been performed at Bristol’s Arnolfini Gallery last Friday, a representative selection of these was this evening presented at CBSO Centre – in the process, confirming that ‘‘while we were all unified by lockdown, our reactions were still highly individual’’.

Tristan Murail’s Les Ruines circulaires was written well before the pandemic, but it vividly encapsulates the ‘dialogues’ aspect – clarinet and violin in confrontation, before opening out into a melodic discourse in a two-way process that might always be the same, only different.

It was vividly realized tonight, violinist Colette Overdijk then having two solo pieces – the first a live hearing for Ma Xiao-Quing’s evocative Back to the Beginning which, while less demonstrative than the online premiere, integrated elements of music and speech with greater subtlety and finesse. Donghoon Shin’s Couplet placed its expressive contrasts in stark relief – thus, an ‘aria and toccata’ in which long-breathed lyricism was succeeded by music whose gestural force and its rapidly accumulating energy were rendered with no mean virtuosity.

Between these works, clarinettist Oliver Janes gave the premiere of speak, sing…, where José Del Avellanal Carreño took advantage of new developments in Machine Learning technology – recorded improvisations by the soloist forming a basis for the interaction between ‘human’ responses as written by the composer with ‘artificial’ responses as generated by the prism-samplernn programme. The outcome was an eventful and unpredictable dialogue, though the subfusc quality of the electronic element rather stood in the way of more engaging synthesis.

Steve Reich’s New York Counterpoint was no less radical in its interplay between clarinet and tape four decades ago, Janes (understandably) sounding more at ease in the dialogue with his pre-recorded self in this performance of appealing deftness and not a little quizzical humour. Beforehand, percussionist Julian Warburton took the stage for the live premiere of R, where Emily Howard explores geometrical concepts as well as the possibilities of sonic growth and decay in a piece whose variety is more immediate given its concision and sense of purpose. Afterwards, Harrison Birtwistle’s The Message provided a telling foil in its halting dialogue between clarinet and trumpet – tersely curtailed by the arrival of military drum; a piece that commemorates the fortieth anniversary of the London Sinfonietta in the pithiest of terms.

Framing the whole, two versions of Celeste Oram’s Counting Steps anticipated then reflected on what was heard. Taking its cue from Fux’s treatise Gradus ad Parnassum, specifically two aphorisms with their expressing strength through courage in the face of weakness and decay, its methodically elaborating trumpet part against a graphic video projection was confidently rendered by Ryan Linham – with, in the second version, Amelie Thomas hardly less assured in support. An arresting framework in which to present this always enterprising programme.

You can find information on the next BCMG live performance here, while Colette Overdijk gives the online premiere of Back to the Beginning here

The mid-afternoon ‘Tombeau de Debussy’ juxtaposed pieces from the supplement published by La Revue musicale in 1920 with commissions under BCMG’s Sound Investment Scheme. Jungeun Park’s Tombeau de Claude Debussy found violinist Alexandra Wood, cellist Ulrich Heinen and pianist Richard Uttley (above) evoking the composer’s death in darkly ironic terms, then the oblique tonality of Dukas’s La plainte, au loin, du faune … seemed as much a memorial to the creative impasse as to its passing. Highly sensitive here, Uttley was no less probing in the moody ‘Sostenuto rubato’ that Bartók incorporated into his Eight Improvisations; soprano Ruby Hughes joining him for the whimsical profundity of Satie’s setting of Lamartine in En souvenir. Sinta Wallur’s Tagore Fireflies sets three brief verses by the Indian poet in music whose ornamented vocal was complemented by the piano’s gamelan-like patterning. Wood and Heinen found requisite plangency in the first movement of Ravel’s Duo; then cellist and soprano took on engaging theatricality for Frédéric Pattar’s setting of Maeterlinck in (… de qui parlez-vous?). Uttley captured the bluesy elegance of Goossens’s Pièce, before Julian Anderson’s Tombeau united the musicians in a setting of Mallarmé’s tribute to Edgar Allen Poe whose chiselled vocal writing and guitar-like sonorities made for a provocative ending.

The mid-afternoon ‘Tombeau de Debussy’ juxtaposed pieces from the supplement published by La Revue musicale in 1920 with commissions under BCMG’s Sound Investment Scheme. Jungeun Park’s Tombeau de Claude Debussy found violinist Alexandra Wood, cellist Ulrich Heinen and pianist Richard Uttley (above) evoking the composer’s death in darkly ironic terms, then the oblique tonality of Dukas’s La plainte, au loin, du faune … seemed as much a memorial to the creative impasse as to its passing. Highly sensitive here, Uttley was no less probing in the moody ‘Sostenuto rubato’ that Bartók incorporated into his Eight Improvisations; soprano Ruby Hughes joining him for the whimsical profundity of Satie’s setting of Lamartine in En souvenir. Sinta Wallur’s Tagore Fireflies sets three brief verses by the Indian poet in music whose ornamented vocal was complemented by the piano’s gamelan-like patterning. Wood and Heinen found requisite plangency in the first movement of Ravel’s Duo; then cellist and soprano took on engaging theatricality for Frédéric Pattar’s setting of Maeterlinck in (… de qui parlez-vous?). Uttley captured the bluesy elegance of Goossens’s Pièce, before Julian Anderson’s Tombeau united the musicians in a setting of Mallarmé’s tribute to Edgar Allen Poe whose chiselled vocal writing and guitar-like sonorities made for a provocative ending.

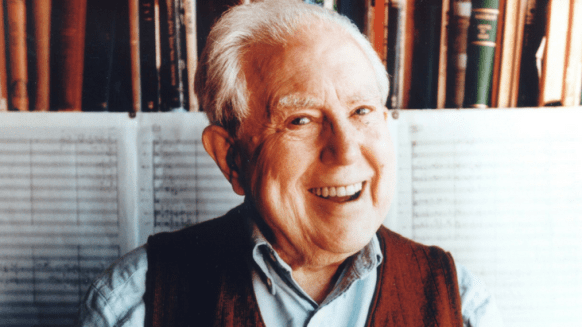

Sunday afternoon brought Birmingham Contemporary Music Group in a programme devoted to Debussy’s Legacy. Boulez’s Dérive 1 (1984) set the scene with its wave-like eddying of pithy motifs, then the music of Tristan Murail (above) took centre-stage with pieces from across three decades of his career. Treize Couleurs du soleil couchant (1978) is a reminder of how radical yet understated (à la Debussy) his music must have sounded in a French scene dominated by Boulezian serialism, harmonic overtones a constant around which the ensemble inhales then exhales its glistening timbres. How Murail got there was duly underlined by Couleur de mer (1969): almost his first acknowledged work, its five sections pit serial constructions against a more intuitive take on harmony and texture in music whose eruptive central span is almost as startling as its cadential sense of closure. Between these, Feuilles à travers les cloches (1998) is an evocative and eventful miniature anticipating the stark post-impressionism of Murail’s more recent music. Fastidious playing from BCMG, and perceptive direction by Julien Leroy.

Sunday afternoon brought Birmingham Contemporary Music Group in a programme devoted to Debussy’s Legacy. Boulez’s Dérive 1 (1984) set the scene with its wave-like eddying of pithy motifs, then the music of Tristan Murail (above) took centre-stage with pieces from across three decades of his career. Treize Couleurs du soleil couchant (1978) is a reminder of how radical yet understated (à la Debussy) his music must have sounded in a French scene dominated by Boulezian serialism, harmonic overtones a constant around which the ensemble inhales then exhales its glistening timbres. How Murail got there was duly underlined by Couleur de mer (1969): almost his first acknowledged work, its five sections pit serial constructions against a more intuitive take on harmony and texture in music whose eruptive central span is almost as startling as its cadential sense of closure. Between these, Feuilles à travers les cloches (1998) is an evocative and eventful miniature anticipating the stark post-impressionism of Murail’s more recent music. Fastidious playing from BCMG, and perceptive direction by Julien Leroy.

Nor is humour at a premium in this music. Two Controversies and a Conversation finds the piano at first mediating precariously between ensemble and percussion (first marimba, then woodblocks), before more balanced and equable discourse is made possible.

Nor is humour at a premium in this music. Two Controversies and a Conversation finds the piano at first mediating precariously between ensemble and percussion (first marimba, then woodblocks), before more balanced and equable discourse is made possible.