Poesie, detail from the Beethoven-Frieze (1902) by Gustav Klimt

Symphony no.1 in C major Op.21 for orchestra (1799-1800, Beethoven aged 29)

Dedication Baron Gottfried van Swieten

Duration 30′

1. Adagio molto – Allegro con brio

2. Andante cantabile con moto

3. Menuetto: Allegro molto e vivace

4. Adagio – Allegro molto e vivace

Listen

Background and Critical Reception

Beethoven took his time before setting down his first symphonic work. Aware of the prowess already shown by Haydn and Mozart, he wanted to be on a sure footing with his first contribution to the form, and used a big concert in Vienna to make his move. The concert contained a major Mozart symphony – thought to be the Prague or the Jupiter – an aria from Haydn’s The Creation, and three major Beethoven works. The first was the Septet, fresh off the page, thought to have been followed by the First Piano Concerto and, finally, this new Symphony.

Reaction was favourable, the only slight criticism an observation that the wind section enjoyed a much higher profile than previously. Beethoven’s other formal inventions were subtle enough to ease the audience into the first part of a transition – with the most inventive tactic deployed early on. The very first chord is the key – C major, but with an added B flat – the seventh – pointing the music towards F major. It may not seem a massive switch but listen to the first chord and you will hear just how different its emphasis is, the first time a composer had tried such a trick in a symphony.

Having pointed this out Jan Swafford is keen to emphasise the traditional aspects of the symphony, the first movement proceeding with ‘a vigorous, military-toned Allegro con brio, its phrasing foursquare, its modulations modest, its development and coda not excessively long’. Similar observations are made on the cautious aspects of the other three movements, though the Minuetto is noted to be a ‘dashing’ scherzo. Overall, for Swafford, ‘as a composer of symphonies and concertos he would rest patiently in the shadow of Haydn and Mozart and experiment with voices while he waited for his muse to show him a more adventurous path.’

Daniel Heartz is more complimentary, though also notes how ‘the symphony as a whole does not reach the level of Haydn and Mozart at their best. All praise to Beethoven, nevertheless, for having the courage to essay a genre that did not come easily to him, and to persevere over four or five years until he was ready to brave public appearance as a symphonist.

A final word to Brahms. ‘I also see that Beethoven’s First Symphony seemed so colossal to its first audiences. It has indeed a new viewpoint. But the last three Mozart symphonies are much more significant. Now and then people realise that this is so’.

Thoughts

While all the critical observations note Beethoven’s caution and respect of tradition in the First Symphony, it is still a remarkable work for its time. It also has great invention, and in a sense Beethoven’s work as an original thinker was already done by the time the first chord had been intoned. Using that particular chord, the C major seventh, would have been a real eyeopener for anybody of the time, a tactic not yet tried that suggested a composer ready to take risks.

As it proceeds the first movement is full of vigorous debate and fulsome writing for wind, an enjoyable dialogue with bags of positive energy. Beethoven writes with great assurance, the dynamic is often loud and the mood upbeat throughout.

In the second movement a tender side is revealed, along with a little wit resembling Haydn – it has a similar profile to the slow movement of his teacher’s Symphony no.100, the ‘Clock’. It also slips into the distant key of D flat major, wholly typical of Beethoven to be thinking further afield with his harmonies, but from here he fashions an effortless return ‘home’.

It may be marked ‘Minuetto’ but there is no way the third movement is anything other than a scherzo. It has a very simple profile – an upwardly rising scale – but Beethoven typically works it into something meaningful. Only 25 seconds in and he’s back in D flat major, showing once again the skill with which he can move between keys. With syncopations and catchy exchanges this is a compact marvel. The trio section is also incredibly straightforward, a series of repeated chords from the woodwind, but once again very effective.

The way Beethoven introduces his main tune in the finale is also very clever, stepping up a ladder one step at a time, returning to earth, then rushing up to the top for the full tune. It generates a good deal of momentum to power this substantial movement, which as Daniel Heartz says represents a desire on the part of the composer to give his works more impetus at the end rather than the beginning. As the symphonies progress we will see this more and more.

Spotify playlist and Recordings used

NBC Symphony Orchestra / Arturo Toscanini (RCA)

Cleveland Orchestra / George Szell (Sony Classical)

Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century / Frans Brüggen (Philips)

Berliner Philharmoniker / Herbert von Karajan (Deutsche Grammophon)

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra / Claudio Abbado (Deutsche Grammophon)

Danish Chamber Orchestra / Ádám Fischer (Naxos)

Minnesota Orchestra / Osmo Vänskä (BIS)

To listen to clips from the recording from the Scottih Chamber Orchestra conducted by Sir Charles Mackerras on Hyperion, head to their website

You can chart the Arcana Beethoven playlist as it grows, with one recommended version of each piece we listen to. Catch up here!

Also written in 1800 Weber Das stumme Waldmädchen

Next up 6 Easy Variations on an Original Theme WoO 77

Woman before the Rising Sun, by Caspar David Friedrich (c1818)

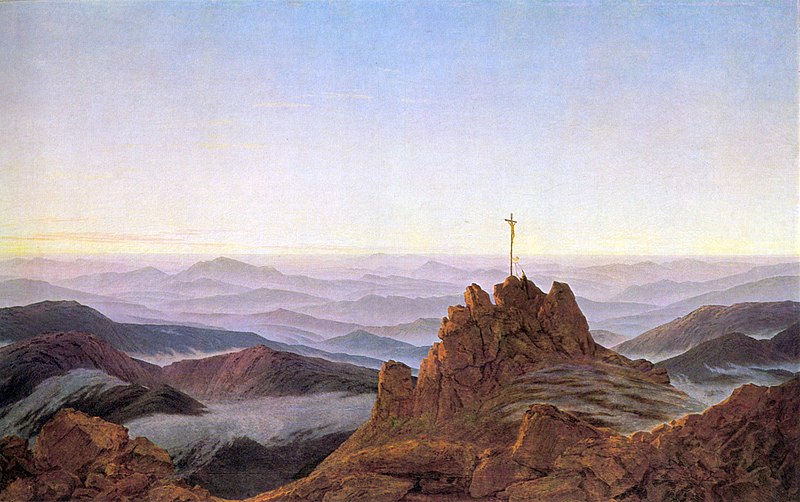

Woman before the Rising Sun, by Caspar David Friedrich (c1818) Morning on the Riesengebringe, by Caspar David Friedrich (1810)

Morning on the Riesengebringe, by Caspar David Friedrich (1810)