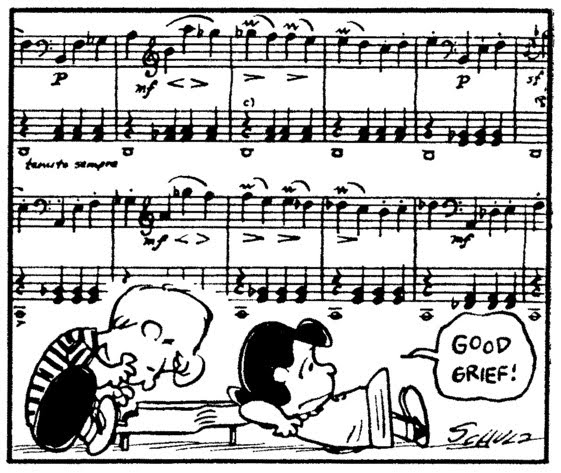

Peanuts comic strip, drawn by Charles M. Schulz (c)PNTS

6 Lieder von Gellert Op.48 for voice and piano (1801, Beethoven aged 30)

1 Bitten

2 Die Liebe des Nächsten

3 Vom Tode

4 Die Ehre Gottes aus der Natur

5 Gottes Macht und Vorsehung

6 Busslied

Dedication not known

Text Christian Fürchtegott Gellert

Duration 14′

Listen

Background and Critical Reception

Although Beethoven was enjoying a fierce period of creativity in his compositions, his health was suffering – and in particular his hearing. This cycle of six Gellert settings captured his state of mind at the realisation that his loss of hearing may well be temporary.

Jan Swafford feels the anguish in songs whose roots go back several years. ‘That Beethoven turned to the artless North German piety of these poems, and set them in a style more interested in declaiming the words than in waxing lyrical, is another indication of his state of mind’, he writes. ‘If doctors could not help him, maybe God could, at least in giving him consolation. These song come from the heart of his anguish and incipient depression.

The texts are revealing, perhaps nowhere more so than the third song Vom Tode, with its line ‘Meine Lebenszeit verstreicht, Stündlich eil ich zu dem Grabe (My life is ending and with each hour I move swiftly to the grave)’.

This is followed by two hymns of praise, before an expansive final song Busslied which explores both sides of the ‘argument’.

Thoughts

The deeper emotion Beethoven has been investing in his instrumental pieces can also be keenly felt in these six settings.

The music of Bitten, in a pure C major, offers a kind of cold and rather downcast consolation, the poet (and composer) contemplating their fate. The tone of Die Liebe des Nächsten, however, is upward looking, and more than a little operatic, the piano answering the voice as a Handel orchestra might have done.

Vom Tode itself has a very hollow ring, and is a sombre affair indeed, one of Beethoven’s most moving songs – and we can surely allow him the exploration of his fate. In the wake of such an empty song, deep in the minor key, Die Here Gott also sounds a little hollow in spite of its status as a genuine hymn of praise. The musical language remains stern, but when Beethoven switches to the major key it becomes genuinely exultant, with massive peals from the piano at the close. Gottes Macht is very much in the same vein, all about strength and power – and here the stance is a Handelian one too.

Busslied is an epic in comparison to these shorter settings, as long as the previous three songs put together. It starts in very withdrawn fashion but moves to a more positive outlook, with a hymnlike melody in the voice. The piano scampers to keep up, turning in some particularly athletic counterpoint.

This is a side of Beethoven we have not yet seen in the vocal music, a deeper and more personal expression which seems more suited to the world of the Lied than the stage. It is a private and rather moving 15 minutes spent with a composer whose physical ailments were destined to challenge him greatly, but ultimately not to overcome his fierce will to compose.

Recordings used

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (baritone), Hartmut Höll (piano) (Warner Classics)

Hermann Prey (baritone), Leonard Hokanson (piano) (Capriccio)

Roderick Williams (baritone), Iain Burnside (piano) (Signum Classics)

Matthias Goerne (baritone), Jan Lisiecki (piano) (Deutsche Grammophon)

These are four really excellent versions, from the ‘old-school’ and imperious approach from Hermann Prey and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau to the newer versions from Roderick Williams and Matthias Goerne. Goerne is especially fine here in his new recording with Jan Lisiecki, finding a moving and reverent stillness in the slower songs and tempering the exuberance of the hymns of praise. Roderick Williams phrases Vom Tode beautifully, with a deliberately flatter tone (not pitch) to the voice.

Spotify links

A playlist of four different versions of the Op.48 Lieder can be found here:

Also written in 1801 Haydn The Spirit’s Song Hob.XXVIa:41

Next up 7 Variations on ‘Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen’