François-Frédéric Guy (piano), Quatuor Danel [Marc Danel & Gilles Millet (violins), Vlad Bogdanas (viola), Yovan Markovitch (cello)]

Weinberg String Quartet no.13 Op.118 (1977)

Shostakovich String Quartet no.13 in B flat minor Op.138 (1970)

Shostakovich Piano Quintet in G minor Op.57 (1940)

Wigmore Hall, London

Thursday 6 March 2025

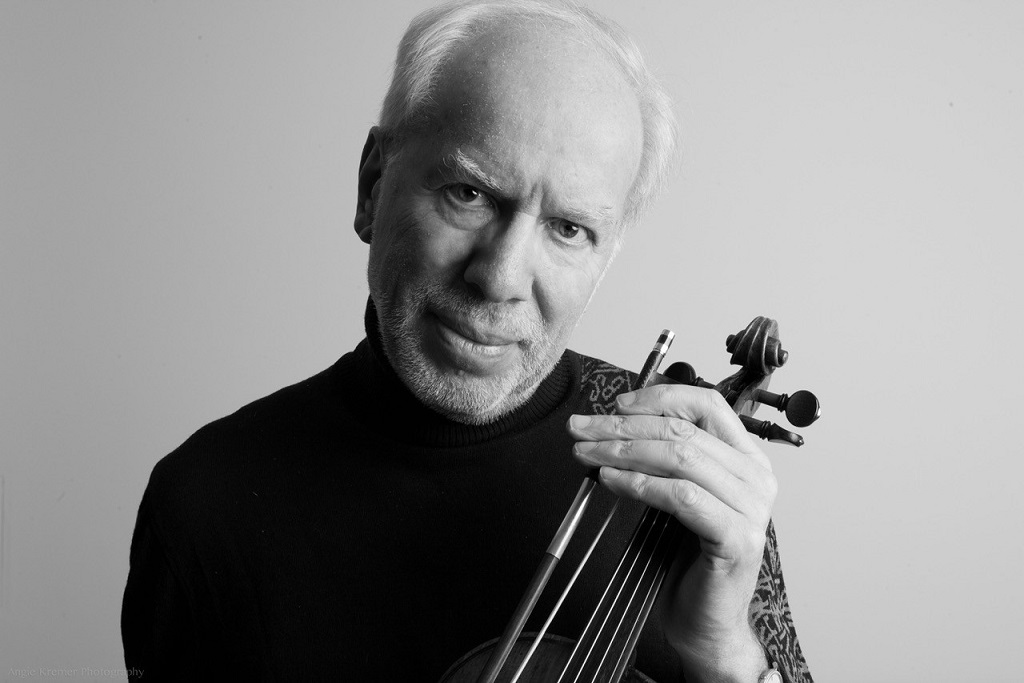

by Richard Whitehouse Photos (c) Marco Borggreve (Quatuor Danel), Lyodoh Kaneko (François-Frédéric Guy)

Quatuor Danel’s cycle at Wigmore Hall focussing on the string quartets of Shostakovich and Weinberg continued this evening with the Thirteenth Quartets by both composers, alongside the Piano Quintet that has long been among the former’s most representative chamber works.

After his exploratory (while not a little disconcerting) Twelfth Quartet, Weinberg avoided the medium for several years before penning four such pieces in relatively swift succession. Cast in a single movement of barely 15 minutes the Thirteenth Quartet, the shortest of his cycle, is influenced as much by Shostakovich’s late quartets as Weinberg’s own precedents. Facets of sonata form underpin its reticent progress from uncertain inwardness to unwilling animation – a vein of equivocation pervading the whole so that its eventual culmination does little more than lead back towards the initial stasis. Its progress enroute is similarly reticent, though this was hardly the fault of the Danel who unfolded the overall design with unforced conviction. Nor did they underplay the plangency of the ending, with its anguished crying into the void.

Seven years earlier, Shostakovich had essayed an altogether more radical take on the single-movement format with his own Thirteenth Quartet. It is dedicated to Vadim Borisovsky, then violist of the Beethoven Quartet, and the viola is audibly ‘first among equals’ over almost its entirety. Nominally the darkest and most forbidding of this cycle, the hymnic lamentation of its outer Adagio sections is thrown into relief by the Doppio movimento central span whose jazz-inflected impetus is but its most fascinating aspect; added to which, those frequent taps onto the body of each instrument (which evoke a death-rattle or a rhythm-stick according to preference) readily accentuate a sense of time running out. Vlad Bogdanas made the most of his time in the spotlight, not least at the close as viola joins with violins to unnerving effect.

After the interval it was a relief to encounter the younger, resilient Shostakovich of his Piano Quintet. Its piano part conceived as a vehicle for himself, this marked the onset of a creative association with the Beethoven Quartet as lasted almost until the end of his life. It also finds the composer immersed in Bachian precedent – witness the powerfully rhetorical dialogue of piano and strings in its Prelude, then the severe yet never inflexible unfolding of form and texture in a Fugue whose abstraction is informed by a pathos the more acute in its restraint.

Playful and capricious by turns, the Scherzo makes for a striking centrepiece in spite (even because?) of its technical challenge. Suffice to add that François-Frédéric-Guy (above) and the Danel met this head on – after which, the Intermezzo mined a vein of soulfulness as was never less then affecting, while the Finale sounded more than unusually conclusive in the way it drew together aspects from the earlier movements towards a whimsical and even nonchalant close. At this stage, Shostakovich could still afford a measure of levity in his emotional response.

Thanks to Marc Danel’s acrobatics with a flying bow, the third movement stayed on course but it was no hardship to have this movement given even more scintillatingly as an encore. May 6th brings the penultimate recital in what has been an absorbing and revelatory series.

You can hear the music from the concert below, in recordings made by Quatuor Danel -including their most recent cycle of the Shostakovich quartets on Accentus:

For more information on the next concert in the series, visit the Wigmore Hall website. You can click on the names for more on composer Mieczysław Weinberg, Quatuor Danel and pianist François-Frédéric Guy

Published post no.2,467 – Saturday 8 March 2025