Composing Myself

by Sir Andrzej Panufnik

(Collected Writings, Volume One)

Toccata Press [477pp, hardback, illustrated, ISBN 978-0-907689-90-4, £80]

Reviewed by Richard Whitehouse

What’s the story?

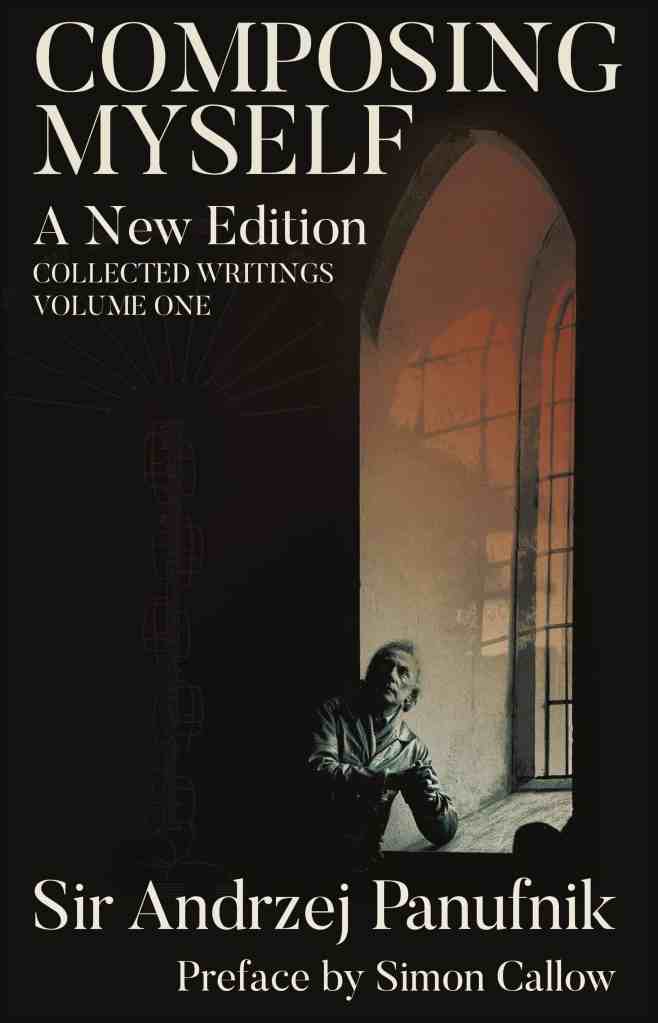

Toccata Press continues its estimable ‘Musicians on Music’ series with this New Edition of Composing Myself – the autobiography of Andrzej Panufnik, first published (by Methuen) in 1987, now reissued with many new annotations, photographs and an end-piece by his widow.

What’s the book like?

Panufnik’s life – taking in the unsettled formative period of his youth, traumatic years with Nazi then Soviet occupation of Warsaw and takeover by communist forces loyal to Moscow, then rigid Stalinization of Polish culture on Socialist Realist lines resulting in his defection to the UK – would make a compelling film, and it typifies this composer’s unwavering integrity he pointedly eschews sensationalism or false emotion in its relating. Moreover, such measured objectivity is enhanced by his tangible evoking of an era cruelly obliterated while resulting in the death of his brother and destruction of all his music. The era of his emergence as Poland’s leading composer and conductor, but also a pawn at the hands of his political ‘masters’, is no less absorbing. Panufnik’s subsequent life – his struggle for recognition in an adopted country where his music fell-foul of officialdom while finding favour with conductors such as Leopold Stokowski and Jascha Horenstein – runs parallel to his evolving a mature idiom and, with the support of his second wife Camilla Jessel, the creative renaissance of his last quarter-century.

Panufnik’s text, left unaltered from 36 years before, is rounded out with explanatory footnotes – by Toccata MD Martin Anderson and the composer’s widow – that fill in a background often unclear or conjectural when Poland was still under communist rule. Almost all his friends or colleagues from the pre-war era are accorded brief but pertinent biographies, but the absence of information about his first wife Marie Elizabeth O’Mahoney (Scarlett Panufnik) after the breakdown of their marriage and divorce in 1959 is surprising (she died in seeming obscurity in 1984). There is an effusive Preface by Simon Callow, contextual Editorial Introduction by Anderson and, most valuably, a Postscriptum by Lady Panufnik. This takes the narrative from 1987 with the composer working on his most ambitious work, the Ninth Symphony, through a further 14 years as saw further high-profile premieres and recordings of almost all his major works before his untimely death in 1991. A late addition details the crucial role of MI6 officer (later MP) Neil Marten in Paunfnik’s escaping Polish ‘minders’ while in Switzerland in 1954.

Is it worth reading?

Absolutely. Panufnik’s being a significant cultural figure as well as a major composer should commend this book to anyone at all interested in the history of post-war Europe. Along with almost all those previously reproduced, this new edition features a host of photos unknown or not available in 1987 and which complement the narrative unerringly. This book is otherwise produced to Toccata’s customary high standards, with an index of works and a general index. Specific information on each piece can be found at Panufnik’s dedicated website (see below).

Is it recommended?

Indeed. The book is Volume One of Panufnik’s collected writings, its successor intended to collate the composer’s articles on music and culture together with his numerous programme notes. Hopefully this can be published in time for the 35th anniversary of his death in 2026.

For more information on the book and to explore purchase options, visit the Toccata Classics website