Anne Queffélec (piano)

Mozart Piano Sonata no.13 in B flat major K333 (1783-4)

Debussy Images Set 1: Reflets dans l’eau (1901-5); Suite Bergamasque: Clair de lune (c1890, rev. 1905)

Dupont Les heures dolentes: Après-midi de Dimanche (1905)

Hahn Le Rossignol éperdu: Hivernale; Le banc songeur (1902-10)

Koechlin Paysages et marines Op.63: Chant de pêcheurs (1915-6)

Schmitt Musiques intimes Book 2 Op.29: Glas (1889-1904)

Wigmore Hall, London

Monday 28 April 2025 (1pm)

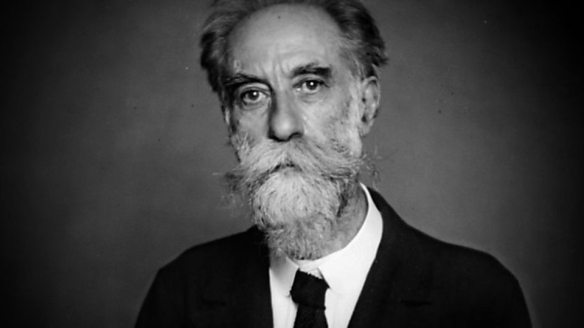

by Ben Hogwood picture of Anne Queffélec (c) Jean-Baptiste Millot

The celebrated French pianist Anne Queffélec is elegantly moving through her eighth decade, and her musical inspiration is as fresh as ever. The temptation for this recital may have been to play anniversary composer Ravel, but instead she chose to look beneath the surface, emerging with a captivating sequence of lesser-known French piano gems from the Belle Époque, successfully debuted on CD in 2013 and described by the pianist herself as “a walk in the musical garden à la Française.”

Before the guided tour, we had Mozart at this most inquisitive and chromatic. The Piano Sonata no.13 in B flat major, K.333, was written in transit between Salzburg and Vienna, and the restlessness of travel runs through its syncopation and wandering melodic lines. Queffélec phrased these stylishly, giving a little more emphasis to the left hand in order to bring out Mozart’s imaginative counterpoint. She enjoyed the ornamental flourishes of the first movement, the singing right hand following Mozart’s Andante cantabile marking for the second movement, and the attractive earworm theme of the finale, developed in virtuosic keystrokes while making perfect sense formally.

The sequence of French piano music began with two of Debussy’s best known evocations. An expansive take on the first of Debussy’s Images Book 1, Reflets dans l’eau led directly into an enchanting account Clair de Lune, magically held in suspense and not played too loud at its climactic point, heightening the emotional impact.

The move to the music of the seldom heard and short lived Gabriel Dupont was surprisingly smooth, his evocative Après-midi de Dimanche given as a reverie punctuated by more urgent bells. Hahn’s Hivernale was a mysterious counterpart, its modal tune evoking memories long past that looked far beyond the hall. Le banc songeur floated softly, its watery profile evident in the outwardly rippling piano lines. The music of Charles Koechlin is all too rarely heard these days, yet the brief Le Chant des Pêcheur left a mark, its folksy melody remarkably similar to that heard in the second (Fêtes) of Debussy’s orchestral Nocturnes.

Yet the most striking of these piano pieces was left until last, Florent Schmitt’s Glas including unusual and rather haunting overtones to the ringing of the bells in the right hand. Queffélec’s playing was descriptive and exquisitely balanced in the quieter passages, so much so that the largely restless Wigmore Hall audience was rapt, fully in the moment. Even the persistent hammering of the neighbouring builders, a threat to concert halls London-wide, at last fell silent.

Queffélec had an encore to add to her expertly curated playlist, a French dance by way of Germany and England. Handel’s Minuet in G minor, arranged by Wilhelm Kempff, was appropriately bittersweet and played with rare beauty, completing a memorable hour of music from one of the finest pianists alive today.

Listen

You can listen to this concert as the first hour of BBC Radio 3’s Classical Live, which can be found on BBC Sounds. The Spotify playlist below has collected Anne Queffélec’s available recordings of the repertoire played:

Published post no.2,517 – Tuesday 29 April 2025

Kari Kriiku (clarinet), BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra / Ilan Volkov, live from City Halls, Glasgow, Thursday 14 January 2016

Kari Kriiku (clarinet), BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra / Ilan Volkov, live from City Halls, Glasgow, Thursday 14 January 2016