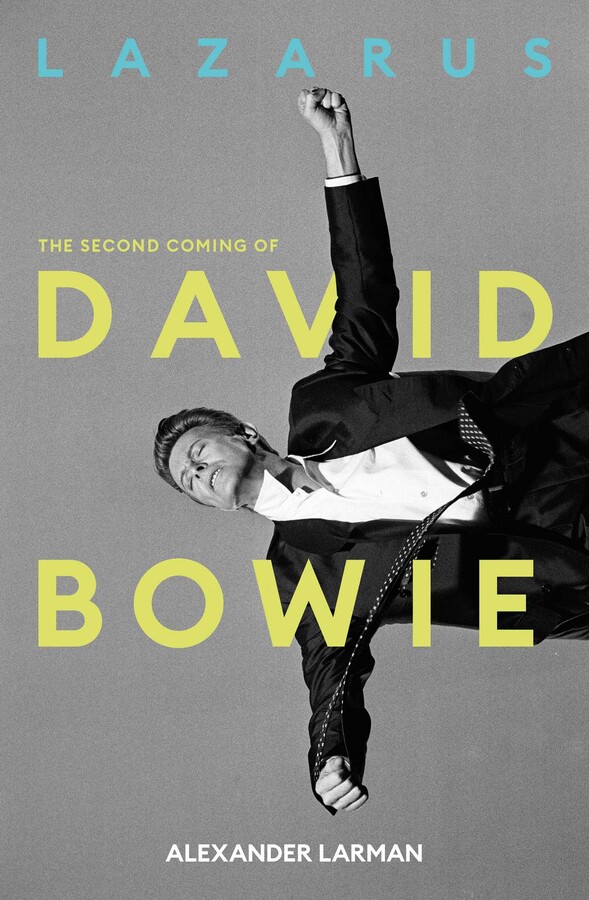

Lazarus: The Second Coming of David Bowie

by Alexander Larman

New Modern 2026 (hardback 432 pages, ISBN: 9781917923446)

Reviewed by John Earls

On 25 June 2004 David Bowie suffered a near-fatal heart attack whilst on stage in Scheeßl in Germany. Alexander Larman begins his absorbing new book Lazarus: The Second Coming of David Bowie by contemplating what might have happened had Bowie died in 2004 and what this might have meant for his reputation.

Bowie had been in the middle of a comeback following a much-praised Glastonbury headlining performance in 2000 and had released the albums Heathen (2002) and Reality (2003). Whilst something of a bounce back from the embarrassment of his late 1980s output, Reality wasn’t his best work nor would it have been an appropriate memorial to such a great artist who would chiefly be remembered for his outstanding achievements of the 1970s and early 1980s.

Of course, Bowie didn’t die in 2004. He went into a period of retirement and recovery and came back with The Next Day album in 2013 and the exceptional Blackstar album, which was released on 8 January 2016, Bowie’s 69th birthday. Two days later Bowie died of liver cancer.

In a bid to challenge the common marginalisation of a significant chunk of Bowie’s latter-day career, Larman presents this book as “the pensive B-side to the triumphant A-side of his heyday”. It is an illuminating delve into this particular chapter of Bowie’s life. Comprehensively researched and drawing on many interviews and reviews of the time, it also features some important and revealing original contemporary interviews. Not least of these are those with Reeves Gabrels – “the man who would become [Bowie’s] most consistent, and important, collaborator throughout the 1990s” and the pianist Mike Garson, who first worked with Bowie in 1972 and played on many of his albums and tours, who gives some insightful and moving contributions.

The book is mostly structured in chronological order starting with the much-derided Tin Machine project whereby Bowie was a member of the four-piece band formed in 1988. Larman has already reminded us in his prologue of Jon Wilde’s infamous 1991 review of the second Tin Machine album which concludes, “Hot Tramp! We loved you so. Now sit down, man. You’re a fucking disgrace”.

We are also reminded of Bowie’s rather mocking appearance with Tin Machine on Terry Wogan’s BBC TV show in August 1991 – Wogan is reported to have subsequently said that Bowie was the most difficult interviewee he’d encountered. But if Tin Machine is one of the most scorned parts of Bowie’s career, for Larman it was “important for both introducing him to [Reeves] Gabrels and for, in Bowie’s estimation, whetting his almost blunted purpose and teaching him how to be a rock star again”. From here the book takes us through his next phase including the making of Black Tie White Noise (1993) which saw Bowie reunited (less than happily) with Nile Rodgers who had co-produced the hugely successful Let’s Dance album (1983).

The Bowie on Screen chapter looks at Bowie’s film activity in this period including playing Andy Warhol in Julian Schnabel’s Basquiat (1996) and a small part in Martin Scorcese’s Last Temptation of Christ (1988). I was particularly intrigued to discover that when Scorcese was toying with a biopic of George Gershwin, Fred Astaire suggested before his death in 1987 that Bowie was the sole actor who he would allow to play him (Astaire) on screen. This chapter also contains an example of some of Larman’s teases as, in one of a number of Bowie lyric references, he says of Gunslinger’s Revenge (1998) that “the film, unfortunately, is a saddening bore”.

In the chapter on Bowie’s fine art activities, he has the delicious line “It is the prerequisite of every wealthy middle-aged man to have his own boutique publishing business”. This refers to Bowie founding 21, a small fine art publisher that published the book Nat Tate: An American Artist, 1928-1960 by William Boyd, which had a New York launch in Jeff Koon’s studio on 1 April 1998. However, no such artist exists and the hoax was exposed a week later in a gossip column in the New York Herald Tribune. The chapter also covers Bowie’s own exhibition New Afro / Pagan and Work 1975-1995 (1995) – largely pilloried by the critics – and his time on the board of the Modern Painters publication (which he had also written for).

There are also sections on some of Bowie’s other non-musical ventures including the launch of the internet service provider BowieNet in 1998 and the selling of ‘Bowie Bonds’ in 1997, giving investors a share in Bowie’s future royalties for 10 years.

But it is the music that is foremost and Larman walks us through the albums and tours from Tin Machine until Bowie’s “wilderness years”. I was grateful to be reminded of how good the much neglected The Buddha of Suburbia (1993) is and to revisit the best bits of Toy (posthumously released in 2021 but recorded in 2000). I also enjoyed slightly rubbing up against Larman’s own evaluation of some of the albums – I’m not quite as enthusiastic as he is about Outside (1995) or as scathing of Earthling (1997), but these are mostly marginal differences and his general assessments are sound and well argued.

One of the most touching passages of the book concerns a BBC Radio One interview Bowie did with Mary Ann Hobbs in New York on 7 January 1997 to mark his 50th birthday. Questions and tributes from celebrities are presented and subject to banter and then we get a “sudden, fleeting insight into the real, unvarnished David Bowie”. The cause of Bowie’s unguarded few minutes is a recorded personal message from Scott Walker which leaves Bowie speechless before he admits: “You really got me there, I’m afraid…He’s probably been my idol since I was a kid. That’s very moving.” You can hear it for yourself on the internet.

The closing chapters cover Bowie’s extraordinary return to the limelight that was the January 2013 release Where Are We Now with its remarkable and somewhat unsettling video, the subsequent album The Next Day, the opening of the David Bowie Is exhibition at London’s V&A Museum and the theatre musical show Lazarus (premiered in 2015) written with Enda Walsh and directed by Ivan van Hove. The song Lazarus from the show features on Bowie’s final album Blackstar (2016) and was to be the last Bowie single released during his lifetime. The astonishing video made for the track was released on 7 January 2016, three days before Bowie’s death.

Blackstar is the culmination of opinions about Bowie’s albums converging back into universal acclaim. It is unquestionably a masterpiece and all the more incredible knowing the circumstances in which it was made.

Larman acknowledges in a final Bonus Track postscript that he did not have access to the Bowie archive at the David Bowie Centre at the new V&A Storehouse East in east London which opened in September 2025 whilst writing the book. One can only imagine what difference it might have made. Nonetheless, his book is a welcome and original contribution to a less explored period in Bowie’s career and its significance.

John Earls is Director of Research at Unite the Union and posts at @johnearls.bsky.socialon Bluesky and @john_earls on X. You can subscribe (free) to his Hanging Out a Window Substack column here: https://johnearls.substack.com/

Published post no.2,800 – Monday 16 February 2026

Friendly Fire – Natalia Gutman (above), London Philharmonic Orchestra / Vladimir Jurowski

Friendly Fire – Natalia Gutman (above), London Philharmonic Orchestra / Vladimir Jurowski