Nielsen Helios Overture FS32 (1903)

Grieg Piano Concerto in A minor Op. 16 (1868)

Sibelius Symphony No. 1 in E minor Op. 39 (1898-9)

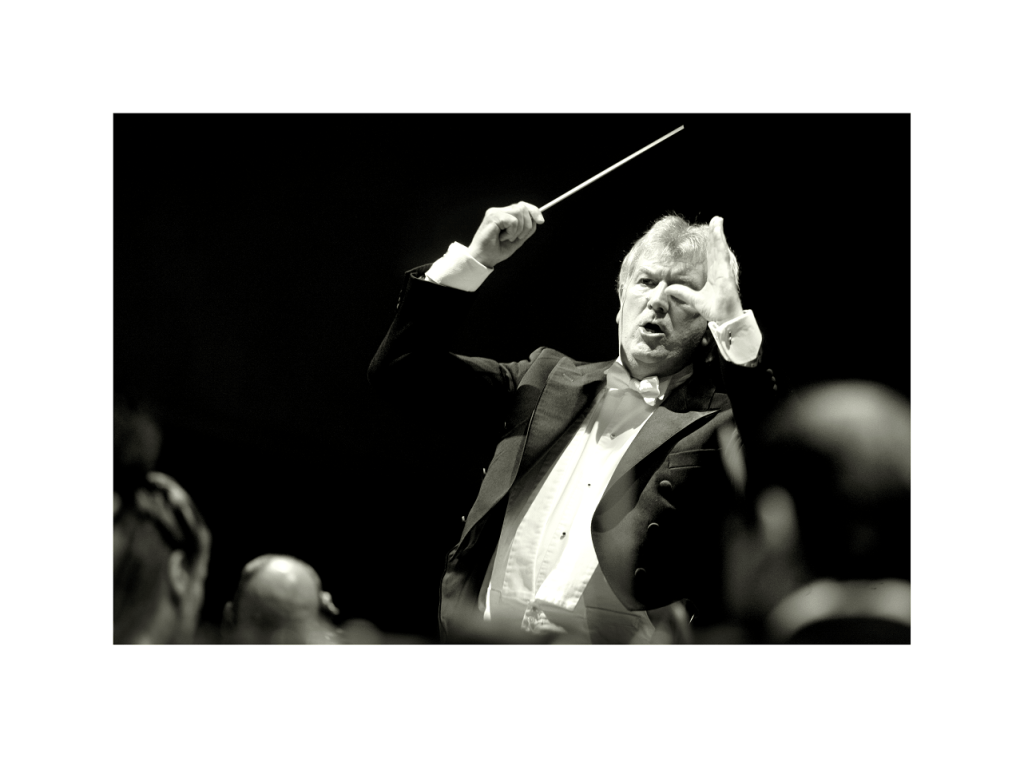

Clare Hammond (piano, above), City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra / Michael Seal

Symphony Hall, Birmingham

Wednesday 9 March 2022 (2.15pm)

Written by Richard Whitehouse

A Scandinavian programme this afternoon from the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, featuring music by the three most famous of this region’s composers (so no representation for Sweden), and presided over with his customary authority by CBSO’s associate conductor Michael Seal.

Unusual nowadays to have a programme consisting of overture, concerto and symphony – but Nielsen’s Helios is as fine a curtain-raiser as any, its ‘sunrise to sunset’ scenario captured with one of the most graphic crescendos and diminuendos in the literature. Seal ensured this gradual emergence, and its faster evanescence, were unerringly paced – the horns’ echoing sonorities enfolded into the orchestral texture; and if the intervening intermezzo and fugato rather tread water by comparison, their role within the formal scheme made for a cohesive overall entity.

Whether or not Grieg tired of hearing or at least playing his Piano Concerto, he would surely have appreciated Clare Hammond’s take on its solo part. The inedible opening gesture might have been less than usually arresting, but the opening movement proceeded methodically and often poetically so its structural seams were barely in evidence – culminating in a resourceful account of the cadenza with the composer’s motivic ingenuity much in evidence. Easy to pass off as a bland interlude, the Adagio had an appealing poise that opened into keen pathos at its height. Trenchant rather than impetuous, the outer sections of the finale were rarely less than engaging but it was the warm soulfulness at the centre that really struck home; its return for a triumphal apotheosis did not quite avoid portentousness, but it ensured a decisive conclusion.

A distinctive and, for the most part, convincing performance which Hammond followed with the caressing harmony of the eleventh from Szymanowski’s Op. 33 Etudes – music in marked contrast to the existential drama of Sibelius’s First Symphony which came after the interval.

The latter work’s emergence against a background of fraught self-determination has inevitably taken on far greater resonance during recent weeks, and it was to Seal’s credit that he played down any tendency to overt sentiment – rendering the first movement, its sombre introduction limpidly realized by Oliver Janes, as the striking and frequently innovative study in expressive contrasts it should be. Nor was there any lack of Tchaikovskian pathos in the Andante, whose whimsical passages were as vividly delineated as those eruptive outbursts towards its climax.

The ensuing Scherzo had the right rhythmic tensility and, in its central trio, enticing whimsy – but it was the Finale as set the seal on this performance. The ‘Quasi una fantasia’ marking can result in emotional overkill but Seal kept its prolix follow-through in focus at all times – whether with the anguished recall of the work’s initial theme, surging impetus of its swifter sections, or the heart-on-sleeve immediacy of its ‘big tune’; pervaded by an ambivalence to the fore in a peroration which (almost) avoided histrionics on the way to its fatalistic close.

A fine response from the CBSO, playing here with burnished eloquence and Matthew Hardy making the most of a timpani part that has structural as well as expressive significance. Few having heard it are likely to underestimate this work’s status in Sibelius’s symphonic output.

For more information on the CBSO’s current season, visit their website. Meanwhile for more information on the artists, click on the names to access the websites of Clare Hammond and Michael Seal