Emmanuel Despax (piano)

Ravel Miroirs (1905)

Despax Sounds of Music – Concert Paraphrase on The Sound of Music by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein (unknown)

Fauré arr. Despax Après un rêve Op.7/1 (1877)

Debussy Clair de lune (1905)

Ravel Gaspard de la nuit (1908)

Bechstein Hall, London, 7 March 2025

by John Earls. Photo credit (c) John Earls

The most recognised piece of music by French composer Maurice Ravel is his 1928 large orchestral work Boléro, famously used in the film 10 and by Torvill and Dean when ice dancing their way to a 1984 Winter Olympics gold medal.

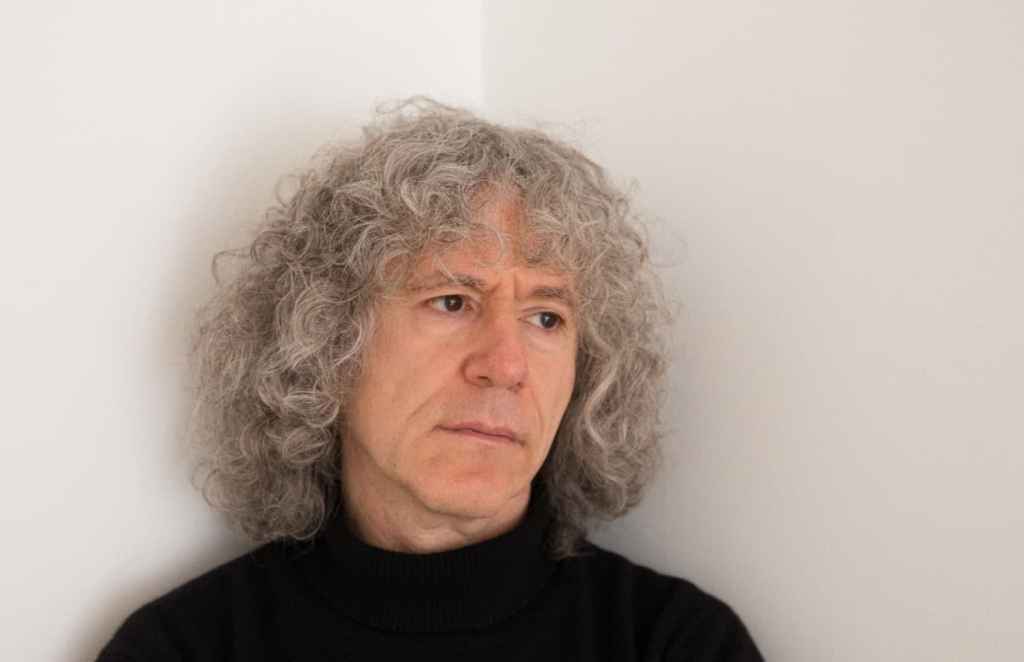

But there is also a magnificent repertoire of piano music including for solo piano and this provided the main feature of this recital by Emmanuel Despax, marking the 150th anniversary of Ravel’s birth.

The first set opened with Miroirs (Mirrors), a suite of five short movements Ravel dedicated to his fellow members of the French avant-garde artist group Les Apaches.

Noctuelles (Night Moths) had twinkling moments of calm surfacing through its dark undertones, contemplative birdsong is evoked in Oiseaux tristes (Sad Birds), Une barque sur l’océan (A Boat on the Ocean) captured both the flow and ripple of the waves, Alborada del gracioso (The Jester’s Aubade) had a jittery, Spanish aspect, and the bells of La vallée des cloches (The Valley of Bells) are not peals so much as melancholic, dark flashes.

The set ended with Despax’s Sounds of Music, a ‘Concert Paraphrase’ on Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The Sound of Music. I enjoyed its dark humour and nods to other classical piano composers – “If you hear something you recognise it’s not plagiarism, it’s on purpose” Despax forewarned us.

The second set opened with Despax’s arrangement of Faure’s Après un rêve (After a Dream) which was serious and majestic followed by Debussy’s Clair de lune (Moonlight) which whilst thoughtful and considered was also beautifully delicate and expressive.

But the evening was Ravel’s and it concluded with his epic three part masterpiece Gaspard de la nuit (Gaspard of the Night) derived from the prose poems by Aloysius Bertrand. Described by Despax as a “symphonic work for solo piano” it is notoriously difficult to play.

Ondine’s hypnotic trills are shaken by a short powerful blast towards the end and Despax displayed his virtuosity throughout. Le Gibet presents bells of a different kind to those featured in the earlier set, more disturbing and ominous as the repeating tolls maintained throughout evoke the lone hanged man of its inspiration. The way Despax leaned into his keyboard in rapt concentration reminded me of jazz pianist Brad Mehldau at his most intense. The final piece, Scarbo, depicts a mischievous goblin and was spritely before its dramatic long pause towards the end and a forceful energetic finish. It was as captivating to watch as it was to listen to.

What was clear from this performance is the attachment and affinity that Emmanuel Despax has for the music of Maurice Ravel. This was confirmed by an encore of Pavane pour une infante défunte (Pavane for a Dead Princess) which provided a moving and tender conclusion to the evening.

John Earls is Director of Research at Unite the Union. He posts on Bluesky and tweets / updates his ‘X’ content at @john_earls

Published post no.2,468 – Sunday 9 March 2025