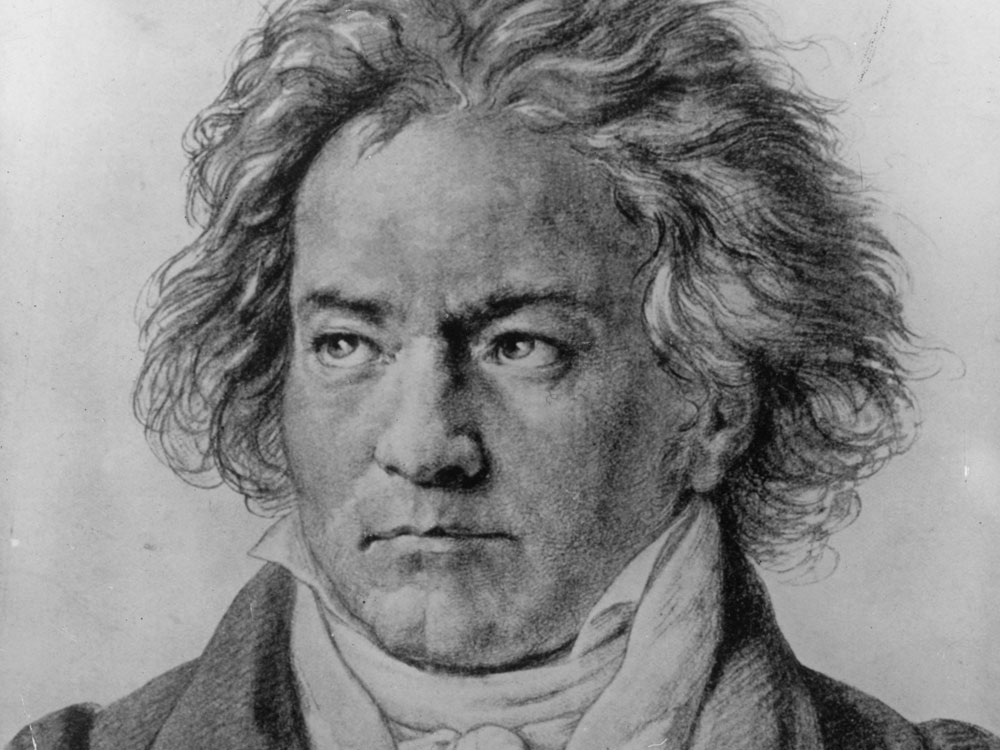

The Hostile Powers. Far wall, detail from the Beethoven-Frieze (1902) by Gustav Klimt

Symphony no.3 in E flat major Op.55 ‘Eroica’ for orchestra (1800-1802, Beethoven aged 31)

Dedication Prince Joseph Franz Maximilian Lobkowitz

Duration 48′

1. Allegro con brio

2. Marcia funebre: Adagio assai

3. Scherzo: Allegro vivace

4. Finale: Allegro molto

Listen

Background and Critical Reception

In October 1803, when Beethoven had completed his third symphony, his world was about to change. His friend, the composer Ferdinand Ries, declared, “In his own opinion, it is the greatest work he has yet written. Beethoven played it to me recently, and I believe that heaven and earth will tremble when it is performed.”

Jan Swafford dedicates a compelling chapter to this work, which was to be one of the very first ‘program’ symphonies. Its dedicatee was to be Napoleon Bonaparte, but in a daring step his heroic character and achievements were to be the subject of Beethoven’s symphonic thoughts, built as they were on thematic cells from music previously written to celebrate Prometheus. Rather than be called Bonaparte, however, the Third took the term Eroica, for Beethoven was horrified by Napoleon’s proclamation as Emperor in May 1804. This was the nickname applied when the symphony was published in October 1806, with the dedication changed to Prince Lobkowitz.

Swafford presents a thoroughly absorbing dissection of the piece in his book, showing how Beethoven’s seemingly innocent sketches and musical cells take wing, blossoming into seamless 20-minute sections of music. The fourth movement, a theme and variations, takes its lead from a melody already used in Die Geschöpfe des Prometheus, completed in 1801, and also from the Eroica Variations for piano.

As Swafford writes, Beethoven “is more interested in flow than in eighteenth-century formal clarity”. At the end of the Eroica’s first movement, “the hero has come into his own, but his task is unfinished”. The symphony is now telling its story about an explicit subject, not just looking to impress on musical terms.

This first movement has a scale and ambition not seen before, as does the second movement funeral march. Berlioz, writing of the whole work, surely had this movement in mind when he declared, “I know few examples in music of a style in which grief has been so consistently able to retain such pure form and such nobility of expression.” The third movement continues Beethoven’s move away from the classical minuet towards the full-blown symphonic scherzo of the 19th century, but it is the finale where all Beethoven’s thoughts are clearly headed.

Swafford explains how Beethoven’s thoughts always had this movement at the head of proceedings, with finale-weighted works still relatively rare at the time. He applauds Beethoven’s innovations for the orchestra, with writing for horns and cellos of a standing not previously experienced. Barry Cooper declares this movement “an extraordinary fusion of musical arts, including variation, fugue, march and slow procession, in a symphonic finale of unprecedented formal complexity despite the apparent simplicity and regularity of its main theme. No wonder Beethoven’s admirers were so thrilled by the work, and the general public so perplexed.”

They were indeed, as Alexander Thayer recounts the puzzlement of an early appraisal. “The reviewer belongs to Herr van Beethoven’s sincerest admirers, but in this composition he must confess that he finds too much that is glaring and bizarre, which hinders greatly one’s grasp of the whole, and a sense of unity is almost completely lost.” Swafford has its measure, however. “The final pages are what the unfulfilled end of the first movement was waiting for, the true victory, the completion of the Hero’s task.”

Thoughts

It is rare indeed to be able to pinpoint an exact moment where art moves from one chapter to the next. Beethoven’s Eroica symphony gives us one such moment, a pivot where the whole notion of the symphony changes for ever and the composer strides forward to a new plain.

So many things about this work are new, exciting, and – for the time – dangerous. The first change is length, for this work often clocks in at near to 50 minutes if the repeats are used, twice the length of a Haydn or Mozart symphony. The first two movements alone are half an hour, making Beethoven’s first two symphonies feel like mere warm-ups in comparison. We also have an increasingly large orchestra to go with the bigger structures, and instruments such as the horn, oboe and cello take on an unprecedented status for their time.

Something is up right from the two brisk chords at the start, a call to attention before the main theme itself. The cellos get their moment, setting the heroic nature of the music in E flat major – which is, as we have seen, one of Beethoven’s key centres for power and positivity. As the massive first movement progresses, the composer goes through intricate yet wholly logical forms of developing his material. There is a new level of emotion here too, for this is a symphony from the heart. Its resolve gives the listener a mental picture of Beethoven beating his chest, giving himself a motivational call to arms as part of an emergence from the terrible days and morale of the Heiligenstadt testament.

The second movement, a funeral march, is one of the most profound utterances we have yet heard from Beethoven. This is the first time he has used the orchestra for such sombre means, other than a few isolated passages in the early cantatas, and the depth of feeling is well beyond previous symphonic thought, bringing closely guarded emotions from the intimacy of the piano to the wide open canvas of the orchestra. This is also a long movement, but the tension is sustained throughout. We feel Beethoven’s grief, his wounds, and also, in the C major ending, a semblance of hope.

The Scherzo picks up on this, easing the tension with its initial subject. It packs a punch recalling the heroism of the first movement, especially with the no-nonsense syncopations. No notes are here for the sake of it, all are fulfilling what feels like an inevitable destiny.

The finale, as Jan Swafford observes, brings everything to a head in a climactic fourth movement not experienced since Mozart’s Jupiter symphony. Few symphonic finales are as thrilling, as Beethoven assembles his melodic material and the music grows in stature at every turn, coming to a peak with a triumphant horn theme. The theme ends with a cadence that shows how Beethoven’s harmonic thinking is advancing with every piece – and indeed caps the sharp dissonance experienced near the start of the first movement. With this and many other elements, you can only imagine what the first audience would have thought, having grappled with the sheer scope of the first three movements. Where was this composer going with his music? Can we take the plunge with him? We will soon find out!

Spotify playlist and Recordings used

NBC Symphony Orchestra / Arturo Toscanini (RCA)

Cleveland Orchestra / George Szell (Sony Classical)

Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century / Frans Brüggen (Philips)

Berliner Philharmoniker / Herbert von Karajan (Deutsche Grammophon)

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra / Claudio Abbado (Deutsche Grammophon)

Danish Chamber Orchestra / Ádám Fischer (Naxos)

Minnesota Orchestra / Osmo Vänskä (BIS)

Berliner Philharmoniker / Rafael Kubelik (Deutsche Grammophon)

Anime Eterna Brugge / Jos Van Immerseel (ZigZag Territories)

The recorded history of the Eroica deserves a much longer article, but safe to say the versions included here represent part of the vast array of available recordings. The smaller scale takes, such as Dausgaard, have plenty to say, as do the lavish accounts from Karajan and dfgd, where the score’s latent power is always in evidence. Accounts from Vänska and dfgd forge a middle ground, while the ‘period instrument’ versions from Brüggen and Jos van Immerseel give us a sense of what the first audience might have experienced, with thrillingly rough edges to the sound and the melodies.

To listen to clips from the recording from the Scottish Chamber Orchestra conducted by Sir Charles Mackerras on Hyperion, head to their website

You can chart the Arcana Beethoven playlist as it grows, with one recommended version of each piece we listen to. Catch up here!

Also written in 1803 Haydn String Quartet in D minor Op.103 (unfinished)

Next up Notturno for viola and piano in D major, Op.42