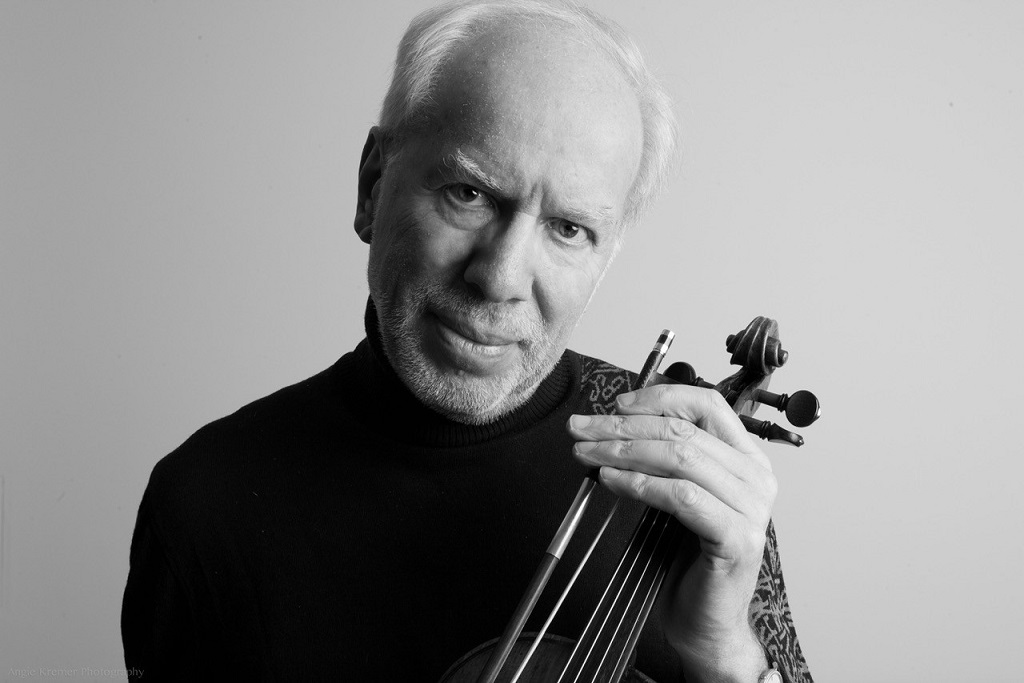

Philharmonia Chamber Players [Mark van de Wiel (clarinet, above), Eugene Lee, Fiona Cornall (violins), Scott Dickinson (viola), Karen Stephenson (cello)]

Gipps Rhapsody in E flat major (1942)

Weber Clarinet Quintet in B flat major Op.34 (1811-15)

Royal Festival Hall, London

Thursday 20 February 2025

Reviewed by Ben Hogwood Picture of Mark van de Wiel (c) Luca Migliore

This free concert in the Royal Festival Hall was a breath of fresh air. Bolstered by visitors, the auditorium was a heartening two-thirds full, the audience made up of families, tourists and workers seeking musical enlightenment. Yours truly fell into the latter category!

The Philharmonia Orchestra have played to this type of crowd for decades now, either by way of introduction to their evening concerts (like this one) or providing a standalone concert focusing on a particular composer (Music of Today) or instrument.

In this instance they covered all bases, with music for clarinet and string quartet introduced from the stage by principal clarinet Mark van de Wiel. The ensemble began with a relative rarity, Ruth Gipps’ Rhapsody in E flat major only coming in from the cold in recent years. Dedicated to her fellow RCM student and future husband, Robert Baker, it is an attractive piece with affection evident from its soft, pastorally inflected first statement. However Gipps’ folk-inspired variant on the opening theme steals the show, firstly heard on cello then subsequently joined by its companions, the clarinet finally singing eloquently over pizzicato strings.

In his talk Van de Wiel’s love of the piece was evident, before he introduced another sleeping giant, Weber’s Clarinet Quintet. Often sitting in the shade of its illustrious companions by Mozart and Brahms, this winsome piece – written for clarinettist Heinrich Baermann – demonstrates just how far the instrument had progressed in the two decades since Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto.

Van de Wiel demonstrated how his clarinet, with 17 keys, was at an advantage to that of Baermann’s ten, in theory reducing the difficulty. His modesty, however, was made clear in the virtuoso demands Weber still makes on the instrument, a fully-fledged soloist, with all manner of tricks up its sleeve.

To Weber’s credit this is not at the expense of musical quality or emotional impact, for although we enjoyed some flights of fancy in the first movement Allegro there was plenty of feeling in the dialogue between clarinet and string quartet. A tender, operatic second movement followed, then an airy and enjoyably mischievous Menuetto rather fast for dancing perhaps but charming all the same. Then came the brilliantly executed finale, living up to its Allegro giojoso marking as Van de Wiel mastered Weber’s increasingly athletic demands with flair and musicality.

Happily both pieces have been recorded as part of a new album forthcoming from the quintet on Signum Classics, where they will team this repertoire with Anna Clyne’s Strange Loops. If the performances match these live accounts, they will constitute a fine document from one of Britain’s very best clarinettists. As though to confirm this, the assembled throng left wreathed in smiles.

For details on the their 2024-25 season, head to the Philharmonia Orchestra website

Published post no.2,452 – Friday 21 February 2025