adapted from the press release by Ben Hogwood

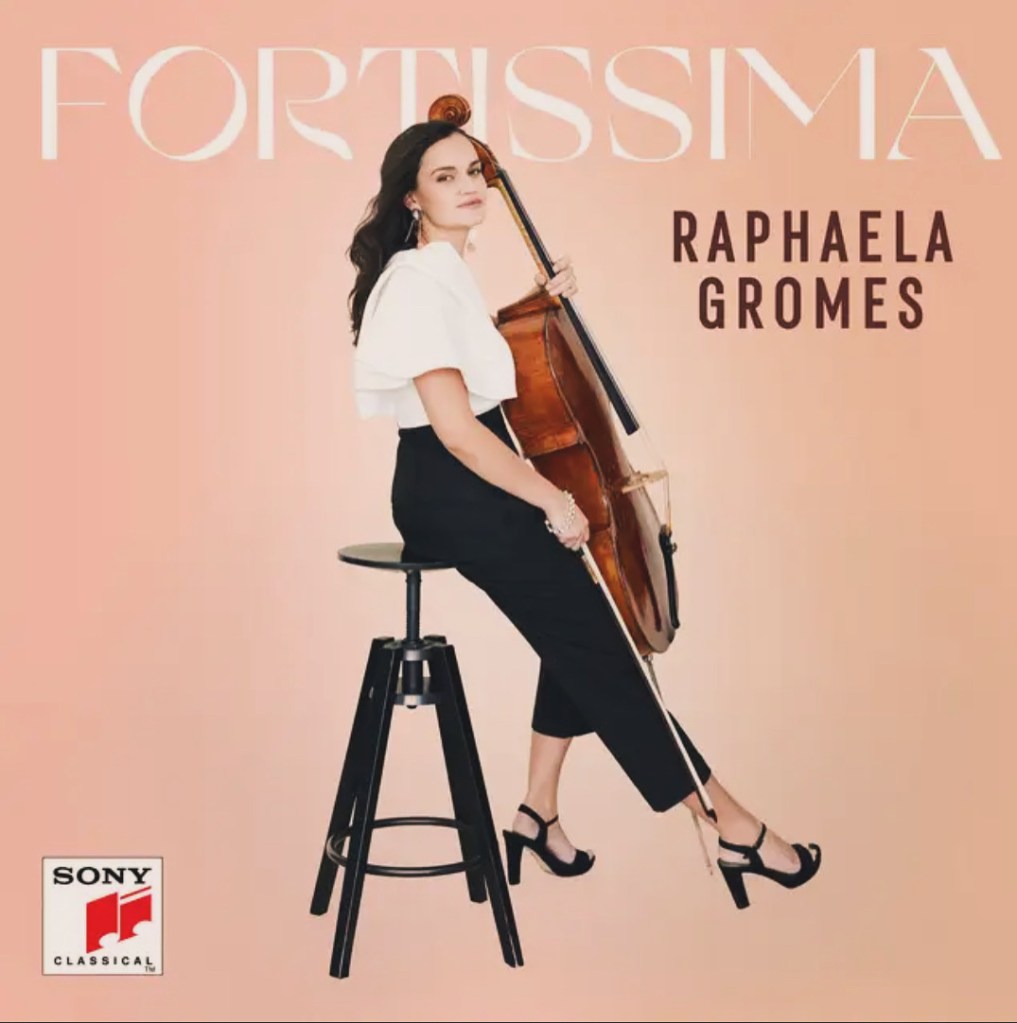

On September 12th, Sony Classical releases Fortissima, the new double album by cellist Raphaela Gromes with the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin (DSO), conducted by Anna Rakitina and featuring Julian Riem on piano:

The album is a compelling collection of numerous world premiere recordings featuring works by neglected women composers. Their remarkable life stories can also be discovered in the book by Raphaela Gromes and Susanne Wosnitzka, published simultaneously in German by Random House. Fortissima is an inspiring musical document celebrating strong women figures who pursued their dreams under adverse conditions and refused to be held back by prescribed societal roles.

“Fortissima is about role models, for everyone, but especially for young women,” states Raphaela Gromes. “The stories of these artists are about personal integrity, the longing for freedom, and irrepressible creativity. It’s not just about outstanding music, but deeply inspiring personalities.”

Raphaela Gromes has been researching the music of women composers for more than five years. Her successful 2023 album ‘Femmes’ was already a result of this work. “In my education and career, I hardly ever came into contact with the music of female composers, and yet there is so much extraordinary music to discover,” explains Raphaela Gromes. “I want to help make these works more widely known and hope they will one day become part of the standard repertoire.”

The first half of the double album is dedicated to compositions for cello and piano by Henriëtte Bosmans, Victoria Yagling, Emilie Mayer, Mélanie Bonis, and Luise Adolpha Le Beau, complemented by an arrangement of All I Ask by Adele. The second half features cello concertos by Maria Herz and Marie Jaëll, a ballade for cello and orchestra by Elisabeth Kuyper, two newly composed orchestral works Femmage I and Femmage II by Rebecca Dale plus an orchestral arrangement of P!NK’s Wild Hearts Can’t be Broken.

Raphaela Gromes was inspired to record Maria Herz’s cello concerto by the composer’s grandson, Albert Herz, who contacted her following a radio programme about her 2023 album ‘Femmes’, which placed women composers firmly in the spotlight. Maria Herz, born in Cologne in 1878 into the Jewish textile dynasty Bing, was forced to flee Nazi Germany and initially lived in England, later in the United States. She left her grandson a large box full of compositions, letters, and pictures, in which the forgotten cello concerto was found. Gromes was instantly captivated upon first browsing the score: the cello leads through an exciting movement with virtuosic solo cadenzas, dense harmonically complex passages, and a jubilant final stretta that evokes the Jewish dance ‘Freylekhs’. Herz began composing after the birth of her four children and, following the death of her husband, sometimes published under a male pseudonym.

The struggle to gain recognition as a female musician and composer was shared by contemporaries Marie Jaëll, born 1846 in Alsace as Marie Trautmann, and Elisabeth Kuyper, born 1877. Although Marie Jaëll was hailed as a musical prodigy and toured across Europe as a child piano virtuoso, a career as a composer largely eluded her. She received private tuition from César Franck and Camille Saint-Saëns and, as personal secretary to Franz Liszt, edited and completed several of his works. Liszt aptly summarised her situation: “A man’s name above her music, and it would be on every piano.” Her virtuosic and moving cello concerto is considered the first such work by a woman and is dedicated to her late husband. Elisabeth Kuyper became the first woman to win the Mendelssohn Scholarship (1905) and was appointed composition lecturer in 1908 in Berlin, another first. Yet a lasting career as a composer and, especially, conductor, was denied her. She subsequently founded several women’s orchestras – in Berlin, London and the USA – all of which eventually failed due to lack of funding. Kuyper died impoverished and forgotten in Ticino. Many of her works are considered lost, including her Ballade for Cello and Orchestra, which Julian Riem reconstructed from a surviving piano score.

Emilie Mayer, born in 1812, and Luise Adolpha Le Beau, born in 1850, were fortunate to gain recognition as composers during their lifetimes. Mayer’s works were performed at the Konzerthaus Berlin, including for King Friedrich III. She had to finance both the performances of her works and their publication herself, which was only possible thanks to an inheritance from her father. The Sonata in A major for Piano and Cello is one of ten surviving cello sonatas. Luise Adolpha Le Beau was supported early on as a pianist by her parents and received lessons from Clara Schumann. She was the first woman to study composition under Josef Rheinberger in Munich and first gained attention for her compositions in 1882 with her Five Pieces for Violoncello Op. 24. The cello sonata Op. 17, recorded by Raphaela Gromes, was even recommended by an all-male jury as a “publishable enrichment.” Henriëtte Bosmans, born in 1895, also received some recognition as a composer in her homeland of the Netherlands, although she was better known as a pianist and, after the war, as a music journalist. Due to her Jewish heritage, she was forced to go into hiding during the Nazi regime and succeeded in rescuing her mother, who had been deported to a concentration camp. Her cello sonata was originally commissioned for the cellist Marix Loevesohn and was composed after the First World War.

Many of the early female composers were initially instrumentalists – a description that particularly applies to Victoria Yagling, a true star cellist. Born in 1946 in the Soviet Union, she studied with Rostropovich and won major competitions. Censorship in the USSR hindered her creative work, and it was only in 1990 that she was able to emigrate to Finland, where she became a highly respected professor. In an era when, in some circles, working as a female musician was equated with prostitution, Mélanie Bonis, born in 1858 in Paris, had to fight even for piano lessons. Exceptionally talented, she was eventually admitted to the Paris Conservatoire at the age of twelve to study with César Franck. Oppressed by her parents and forced into marriage, she suffered from severe depression during the final 15 years of her life. Yet it was during this period that she composed the delicate piece Méditation, which her granddaughter discovered in 2018 in an attic.

Three contemporary works are included on ‘Fortissima’: Femmage I and II were composed especially for Raphaela Gromes by British composer Rebecca Dale (b. 1985). In the reflective, cinematic ‘She walks through History’, Dale places a sweeping melody at the centre to highlight the vocal expressiveness of Raphaela Gromes’ cello playing. In ‘Meditation’, Dale unfolds a harmonically fascinating sound spectrum, with the cello solo rising from its lowest register to extreme heights. The adaptation of Adele’s ‘All I Ask’ pays tribute to one of the greatest soul voices and songwriters of our time, while P!NK’s ‘Wild Hearts Can’t be Broken’ holds special personal significance for Raphaela Gromes. The lyric “My freedom is burning, this broken world keeps turning, I’ll never surrender, there’s nothing but a victory. This is my rally cry.” could also serve as a motto for the women composers featured on the album.

As part of the album’s production, three new sheet music editions were also created: Henriëtte Bosmans’ cello sonata will be published by the renowned Henle Verlag. Marie Jaëll’s cello concerto, now including a newly discovered second movement recorded for the first time on this album, will be published in an edition by Julian Riem at furore Verlag. Elisabeth Kuyper’s Ballade for Cello and Orchestra, whose original score is lost, has been newly orchestrated by Julian Riem and Raphaela Gromes from the surviving piano version and will be published by Boosey & Hawkes.

‘Fortissima’ is released on September 12th by Sony Classical.

TRACKLIST:

CD 1 (feat. Julian Riem, piano)

1. – 4. Henriëtte Bosmans: Cello Sonata in A Minor

5. Victoria Yagling: Larghetto

6. – 9. Emilie Mayer: Cello Sonata in A Major

10. Mélanie Bonis: Méditation

11. – 13. Luise Adolpha Le Beau: Cello Sonata in D Major, op. 17

14. Adele: All I ask

CD 2 (feat. Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, conductor: Anna Rakitina)

1. – 4. Marie Jaëll: Cello Concerto in F Major

5. – 11. Maria Herz: Cello Concerto Op. 10

12. Elisabeth Kuyper: Ballad for Cello and Orchestra, op. 11

13. Rebecca Dale: Femmage I – She Walks Through History

14. Rebecca Dale: Femmage II – Meditation for Cello & Orchestra

15. P!NK: “Wild Hearts Can’t Be Broken”

Published post no.2,644 – Thursday 4 September 2025