William Wordsworth

Piano Sonata in D minor Op.13 (1938-9)

Three Pieces (1932-4)

Cheesecombe Suite Op.27 (1945)

Ballade Op.41 (1949)

Eight Pieces (all publ. 1952)

Valediction Op.82 (1967)

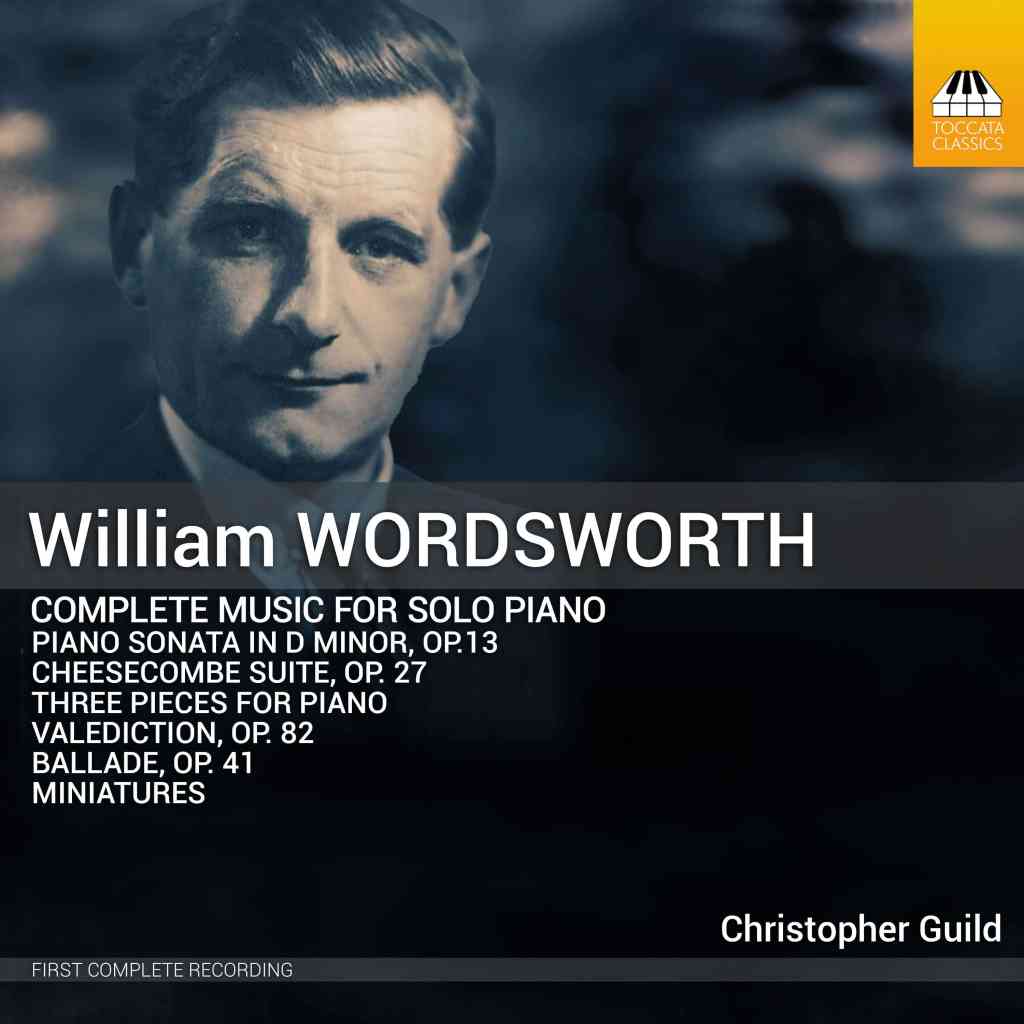

Christopher Guild (piano)

Toccata Classics TOCC0697 [81’08”]

Producer and Engineer Adaq Khan

Recorded 13 April, 29 May 2022 at Old Granary Studios, Beccles, 2 April 2023, Wyastone Hall, Monmouthshire (Three Pieces)

Reviewed by Richard Whitehouse

What’s the story?

Toccata Classics intersperses its continuing survey of William Wordsworth’s orchestral music with a release devoted to that for solo piano, including several works not otherwise recorded and all ably performed by Christopher Guild, who already features prominently on this label.

What’s the music like?

Although not a large part of his catalogue, piano music features prominently in Wordsworth’s earlier output – notably a Piano Sonata that ranks among the finest of the inter-war period. Its first movement is introduced by a Maestoso whose baleful tone informs the impetuous while expressively volatile Allegro. The central Largamente probes more equivocal and ambivalent emotion before leading into the final Allegro, its declamatory and martial character offset by the plangent recall of earlier material prior to a denouement of surging and inexorable power.

His status as conscientious objector found Wordsworth engaged in farm-work in wartime, the experience duly being commemorated in his Cheesecombe Suite whose pensive Prelude and dextrous Fughetta frame a quizzical Scherzo then a Nocturne of affecting pathos. Written for Clifford Curzon, Ballade is a methodical study in contrasts which makes an ideal encore; as, too, might Valediction – though here the emotions run deeper and more obliquely, as befits this inward memorial to a lifelong friend from comparatively late in its composer’s creativity.

This release rounds out our knowledge of Wordsworth’s piano music with two collections not previously recorded. Among his earliest surviving works, the Three Pieces comprise a taciturn Prelude, fleeting Scherzo then soulful Rhapsody which between them find the composer trying out whole-tone figuration with resourcefulness but also a self-consciousness that might have decided him against publishing. Published by Alfred Lengnick as part of its five-volume educational series Five by Ten, the eight miniatures wear their didactic intention lightly; only one of these exceeding two minutes, yet all evince a technical skill that is never facile along with a pertinent sense of evocation that should commend them to amateurs and professionals alike. Here, as often elsewhere, Wordsworth proves a ‘less is more’ composer of distinction.

Does it all work?

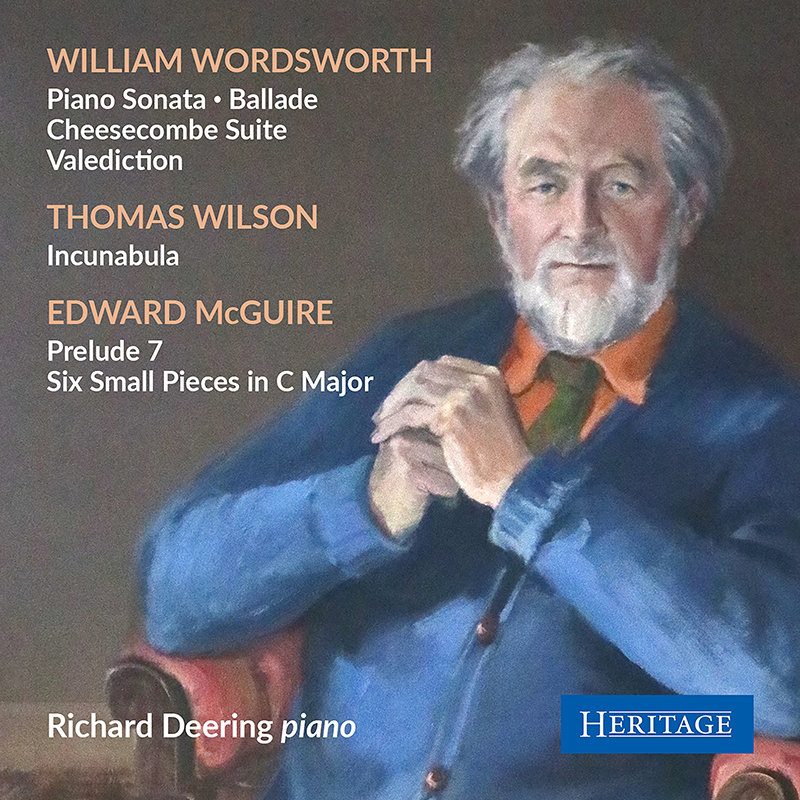

Very much so and Christopher Guild, with admirable surveys of Ronald Stevenson (Toccata) and Bernard Van Dieren (Piano Classics) to his credit, is a natural interpreter of often elusive yet always rewarding music. His charged and often impetuous take on the Sonata has more in common with the pioneering account by Margaret Kitchin (Lyrita) than the overtly rhetorical one by Richard Deering (Heritage). Similarly, his approach to the Cheesecombe Suite and the Ballade draws out their depths if occasionally at the expense of their expressive immediacy. Interestingly, Valediction is played from a copy by Stevenson that alters aspects of keyboard layout or pedalling if not the notes themselves; resulting in a greater emotional ambivalence and textural intricacy which Wordsworth, had he heard it, would most likely have endorsed.

Is it recommended?

Indeed, not least when the sound of both Steinway D’s are so faithfully conveyed and Guild’s annotations are so perceptive. Those who have the Deering release should consider acquiring this one also, while those new to this music need not hesitate in making this their first choice.

Listen & Buy

For purchase options, you can visit the Toccata Classics website. Click on the names to read more about pianist Christopher Guild and composer William Wordsworth.

Published post no.2,500 – Thursday 10 April 2025