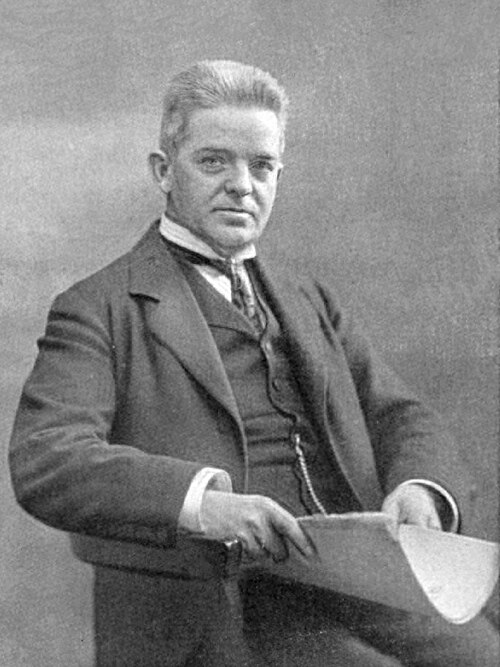

by Ben Hogwood. Image of Carl Nielsen in 1917 – unknown credit, used courtesy of Wikipedia

On this day 100 years ago – the first performance of Carl Nielsen’s Symphony no.6, the Sinfonia Semplice, took place in Copenhagen.

To mark the anniversary, Linn Records made a very intriguing release in September of a special version of the symphony. As the page for the album states, “conductor Ryan Wigglesworth joins Royal Academy of Music’s outstanding young musicians to revisit the composer’s later period. This recording showcases two works by Nielsen in two spellbinding arrangements by fellow-Dane Hans Abrahamsen. The No 6 ‘Sinfonia semplice’, written during a period of declining health, is viewed by some as a strongly ironic work. However, its lightness is also deeply sincere. With its crystalline weightlessness, Abrahamsen’s chamber arrangement reclaims both the quizzical spirit and sense of fragility in the original.

You can hear the album on Tidal by following the link below:

https://tidal.com/album/446995399/u

Published post no.2,745 – Thursday 11 December 2025