Steven Kovacevich Photo: David Thompson/EMI Classics

If you were asked to name some of the world’s greatest living classical pianists, the chances are it would not be long at all until you got to the name Stephen Kovacevich.

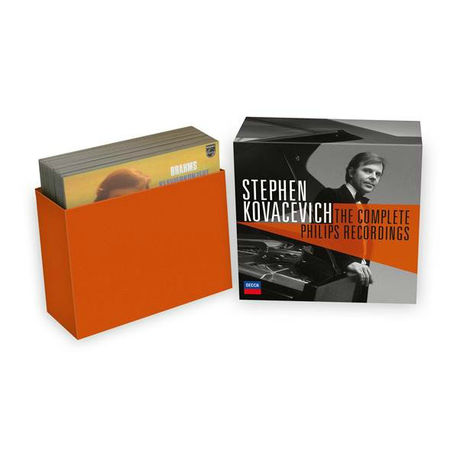

Kovacevich has just reached the age of 75, but despite some recent health problems it is clear when Arcana has the privilege of meeting him that he is in good physical, mental and musical shape. He is the perfect host, too, pouring coffee as we prepare to discuss aspects of his career to this point, based around the recent issue of a handsome box set with the collected recordings he has made for Philips. These include legendary performances of Bartók, Beethoven, Mozart and Brahms – all of which he will discuss over the course of the next half hour.

To begin with, however, it’s back to the start. What are his earliest memories of playing the piano? “I can’t remember the very first one”, he considers, “but I know that it was in San Pedro, about an hour and a half south of Los Angeles. My grandmother had an upright piano, and I probably tinkered with that but I just remember that it was there. I don’t remember much. Then I had at around the age of seven the local piano teacher, who was OK, then I had lessons with a very good teacher in San Francisco where my family moved to Berkeley. I remember thinking that I wasn’t very good, because I found it difficult at the age of eight or nine, but by the age of eleven I was playing quite well. I gave quite a good concert then, and looking back I probably wouldn’t be ashamed of it today – or maybe I would be! Then I studied in San Francisco until I came here to work with Myra Hess, a great artist.”

Myra Hess

“She was a profound artist”, he says of his teacher, “and I had a choice of going to Juilliard, with a scholarship at the college there, or coming to London. I chose London because of the repertoire, and Myra Hess’s repertoire interested me more. Juilliard is so competitive.”

What were the lasting things he learned from study with her? ““I was 18 or 19”, he recalls, “and I could play well, but I think it was rather monotonous in terms of variation of sound. I remember the first lesson was on the Brahms Variations on a theme of Handel.

The theme, which can be sight read, we worked 45 minutes just on that, trying to get a ‘trumpet sound’ that was perfect, a sound that was ‘dolce’. Just working on that started to provoke other areas of your imagination. She was a great teacher, with repertoire that interested me at that time. I hadn’t liked Beethoven very much until I heard her play it, and she really understood late period Beethoven. I was privileged and benefited greatly from that, because genuinely – if immodestly – it was the only music I was interested in.”

I mention to Stephen how I have been listening recently to his recording of Bartók’s Piano Concerto no.2, made with Sir Colin Davis and the London Symphony Orchestra for Philips:

“It’s one of the best I ever did!” he says emphatically. “Everything I could do musically, mechanistically, emotionally, is there, and I was lucky because when I first heard the piece I then went and bought the score. I’m not being coy, but I just didn’t think I could play it! I dropped in on Colin Davis and I wasn’t fishing but I simply said, “Colin, I’ve heard this incredible piece but I think it’s beyond my abilities”. He was in charge at the BBC Symphony Orchestra at the time, and he asked me to play it at a Prom nine months later.”

“I knew if I couldn’t do it that I could always cancel, but that I would never forgive myself for not trying! I had never played anything so difficult – and actually there isn’t anything more difficult! It was the making of me – in some ways a bit too much, because I developed muscles, and a sound which was on the cusp sometimes of being too …but I had it in my repertoire. It made a lot of things possible, but also psychologically, if you can play the third Rachmaninov concerto, the second Bartók, the second Brahms maybe, the Beethoven Hammerklavier Sonata, if you can do these things it gives you a certain pride. The Chopin Études, I can’t play them properly but I can play them alright. But Bartok’s Second I can play. So that gave me some confidence. It’s a frightening piece, you know!”

Kovacevich goes on to reminisce about his early experiences with the concerto. “The first performance I gave was at the Proms, and a very distinguished composer who learned with Myra Hess, he turned the pages for me. In the middle of the second movement he got lost, and just sat down! Thank God the passage is so difficult that I had memorised it. He just sat down and gave up, and this was a live Prom!”

And what about that recording session? Just listening to the results, the listener gets an idea of the sheer adrenalin generated by the performance. “Colin and I had performed it ten times – in New York, and on tour with the Scottish National Orchestra, and in several performances with the BBC. I knew the recording went well because the first performance at the Proms was OK but nothing special. Then the next performance I stopped in the studio recording, but the performance after that was the opening night of the Edinburgh Festival, a live broadcast. I was so terrified I couldn’t even do the BBC balance test. Can you believe it?! They did it cold. There is a passage which I had missed before and two of my friends, very famous and wonderful young players, they embraced each other when it was coming up, and I got through it! And when I did I went completely nuts and really played out of my skull. So I knew if I could survive a concert then I could do a recording. I just went for it, and I remember Colin knew it very well by then too, we knew how we did it together, so we did not have any problems. I think it took three sessions. One session we concentrated on the sound but then we did two and a half sessions on it.”

What was it about Stephen’s relationship with Sir Colin that worked so well? “Well it stopped, but when it worked I can only say there was similar passion and energy, and in those a similar sense of tempo. He then became more spacious, so it didn’t work because I didn’t do that – and both are perfectly valid journeys. At that time he was a firebrand, with the Beethovens and the Brahms and the Bartók. I think he loved the first and third, and that’s appropriate. At the time he was doing the Rite of Spring but interestingly enough he stopped becoming interested in doing it. I had to trust him on it but I didn’t understand it. I think he turned away from that kind of wild stuff. I never heard anyone conduct Berlioz the way he did; I heard two staged performances of The Trojans – just marvellous. Why he stopped, I don’t know, but it did. Thankfully we did more Mozart piano concertos, Schumann, Grieg, Bartók and both Brahms, Stravinsky and all the Beethovens.”

One of Kovacevich’s favourite stories is of his recording with Martha Argerich of Bartók’s Sonata for two pianos and percussion. One of the pianos had been dropped, and was unplayable – but somehow they found a replacement so that recording could take place at an unearthly hour. Was that the right time to record it after all?! “I think the second movement is definitely a late night piece”, he agrees, “but the rest is so difficult – almost as difficult as the Second Piano Concerto. Again it’s a piece of savagery. The first movement, if that’s not an onslaught I don’t know what is! As you know the piano was dropped, and they tried to say that nothing had happened, and then at about 8 at night they were trying to find another piano for the session. Steinway was closed, I don’t know how they found it, but at about two in the morning another piano arrived, and that’s when Martha starts working. I was gaga at that stage but the adrenalin kicked in, and we finished probably around 6:30 or 7:00. If you had said I was going to be recording at 2:30 then of course I wouldn’t have accepted it, but there was nothing else we could do!”

Kovacevich will give a concert at the Wigmore Hall in honour of his birthday, taking place on Monday 2 November. The first half consists of Debussy’s En blanc et noir and Rachmaninov’s Symphonic Dances, both with Argerich at the second piano. When did he last play these pieces? “I last played the Debussy with Martha at her festival in Lugano, about two months ago, so that is in our fingers.

The Rachmaninov is the first time I’ve ever played it, and I just came back from Brussels two or three days ago where we rehearsed. I think our rehearsing is done. My new love is Rachmaninov. I’ve always loved him but now I think I’ve completely fallen for him!” Is that in a sense that makes him want to play his music? “Yes. I’d like to learn some of the solo music, but it’s no joke at my age to learn this type of repertoire, especially when it’s not the kind of repertoire that is my home territory. Now my favourite Rachmaninov concerto is the second. I can’t play it, but I have a few months where I don’t have a concert. I have to learn the Bartók Second Violin Sonata, and I will try and do the Second Piano Concerto or some of the shorter pieces.”

Clearly he still has a keen spirit of discovery, and I ask what it is about Bartók that particularly appeals to him? “The rage, because you feel much of the music – rather similar to Beethoven – has protest, anger, rage at the brutality and suffering that people go through. When you feel it is not just an individual thing, but society is doing it – like the Second World War which was going on – that’s a feeling of oppression. I think he captures that sense of rage and I think Beethoven is the only one to my mind who does it in the same way. Stravinsky’s rage in The Rite of Spring is ferocious, but you don’t feel it is a negative piece. Whereas Bartók’s Duke Bluebeard’s Castle, the String Quartets, the Piano Concerto no.2, the Out of Doors suite – the music of the night and The Chase especially. The Chase (the last movement of Out of Doors) is about one animal chasing another, with a chomp at the end! That’s it, but it is not music for Blue Peter!”

I note that when listening to the Out of Doors Suite, it seems Bartók finds parts of the piano that no one else seems to find. Kovacevich nods. “The piano writing is magnificent, and the music of the night – Ravel or Debussy did not write more exquisite music and super sensitive sonorities, but the music of the night in the second piano concerto, that’s a dark atmosphere, and the chase is frightening.”

This is perhaps why some see Bartók’s music as containing roots of rock, and I suggest it may be why his music has been used in horror films. Stephen agrees, but has more to add. “Another fact that isn’t known about him, which I have read, is that he had the feeling of an isolated person. When he was very young he had a skin disease that was so unpleasant to observe that at that age, only his mother could touch him. It cleared up, and he had beautiful skin after, but there was a feeling that he was probably physically isolated. I’m guessing but I think it stayed with him.”

A love of dance also stayed with Bartók in his music. “Absolutely. You take the Mazurkas of Chopin, you push it a bit further and you get some of the dance rhythms in Bartók. Also a composer who is surprisingly dark sometimes in his dances, but where nobody plays them, is Grieg. He is not the boy next door! I love Grieg. He wrote so little, but Peer Gynt is wonderful. It is also terrifying, and I find Anitra’s Dance scares me! There is a shadow there.”

The Philips set includes Kovacevich’s recordings of the late Brahms piano works, providing a nice contrast to the concertos:

Does he find now that at the age of 75 he appreciates composer’s late works more than he used to? “No, I don’t think so. I have always had a weakness for composers’ third period works. Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert, Brahms as well. I was always intrigued, so I don’t think about that.” Can it go the other way, to exploring composers’ young works? “I enjoy early Beethoven much more now than I did in my twenties, for sure. But the late stuff, there is something about the third periods which is different.”

At the moment Schubert appears to be the one with whom he feels the strongest connection – and his last Piano Sonata, the famous B flat major work numbered as D960:

“This work means a lot to me and to many, many people,” he says. “In the late Beethoven sonatas, in Op.110 the aria speaks so personally about late thoughts, and I think that the B flat sonata in the slow movement is in that area. The sonata before has this amazing outburst in the slow movement, and where does that come from? If you just played that passage, you would never know it was Schubert! It could be Liszt, Rachmaninov, Musorgsky, but never would you think it was Schubert. And where does it come from? Woody Allen, in his film Crimes and Misdemeanors, in the murder scene, he chooses that String Quartet of Schubert with the eerie tremolos at the beginning, they are like a slap in the face. Woody Allen, who knows music upside down, chooses Schubert for moments when the centre does not hold:

Does it feel with the Schubert piano music that he is playing songs sometimes? “I wouldn’t say so. Maybe with some of the Impromptus, but I think when he writes piano sonatas it’s not just melody with accompaniment, there are more ingredients than that.” I comment how in late Schubert it feels like time has stopped sometimes. “Well the late String Quintet is a good example of that, but it is inexplicable. I mean, I love it but I have no idea what it’s all about! There is something there, where the imagination is supercharged from him. And also the lyricism, it defies analysis, you don’t know why it is so beautiful – it just is.”

Given the story of the Bartók session above, I wonder if he has any other unusual stories of recording sessions or performances? “I was doing a Prom once, where I was playing the world premiere of the Piano Concerto by Richard Rodney Bennett, and they had forgotten to lock the wheels of the piano! It was a live broadcast, and as I played the piano started to move away from me, and it went straight into the cello section! So these guys were playing cello and they saw this massive beast heading towards them. The piece begins quite quietly and there is about a ten second break just after you start, so in those ten seconds I reached into the piano, pulled it back to me.

Of course the audience laughed, and this time it didn’t move. That was quite scary! Yet even as I was bowing, the phone rang backstage and the Beeb said, “It’s the Daily Express. Did your piano start to go into the cello section?!” Unlike me I just calmly pulled the piano back. And of course the audience loved it.”

Kovacevich has conducted more recently, and enjoyed a series with the London Mozart Players at the Cadogan Hall, performing all the composer’s symphonies and piano concertos. Did it give him extra insight into the music in any way? “Not into the music, but with conducting it is different to the piano. No matter how anxious you might be you don’t have to play the notes, so when you’re on stage conducting, and you know the piece very well, you can actually concentrate on the music, to a degree more than when you are playing. So I was walking on stage and looking forward to the concert. The first time I performed the Ninth Symphony I was looking forward to it! The first time I played the Emperor Concerto I wasn’t looking forward to it!”

“I loved conducting”, he says. “I’ve conducted the Beethoven Symphonies, the Brahms, Sibelius‘ Fourth, the Tchaikovsky Pathétique. I wanted to do those pieces. I’ve lost interest, I don’t know why exactly – I think because when I am conducting I have to concentrate so much that part of my concentration is actually on playing the piano. I have done all the Beethoven concertos from the keyboard, and I find it easier to play them when I’m conducting too – I think the Emperor paradoxically is easier to play! The Fourth is harder to coordinate, as it has more flexibility, and when we performed we placed the piano in the middle of the orchestra so that the winds and I could hear each other. I loved doing those concerts at the Cadogan Hall where we did the concertos and symphonies.”

What role has music played in Stephen’s life outside of performing? “It has been a source of consolation, which is one of the things that music is for. Late Beethoven when I was younger was a source of consolation. I remember being very blue and Wagner‘s Die Meistersinger getting me out of it night after night. Also Brahms – it’s like someone consoling you.”

And does he listen to any music besides classical? “I like the ‘black jazz’ from America in the 1930s and 1940s and I love the American musicals, I think they are phenomenal. I love Gershwin, I think he’s phenomenal, and he has a lyrical gift which is fabulous, really inspiring. The fact he and Schoenberg used to play tennis in Los Angeles – can you imagine?!”

Talk turns to audiences, and more specifically how classical music could boost its own. “How often, especially in the days when I dressed in tails to go to a concert – you would get into a taxi and the driver would say what you are doing? I would say I’m playing a concert – do you ever go? “No”, would be the response. Do you enjoy it? “Yes”. Why don’t you go? I don’t know how many times but the response is “I’m embarrassed – I wouldn’t know how to behave”. I know the same thing. I would love to go more jazz, but I’m shy to go to a jazz club because I think I would not know how to behave. The feeling of sticking out – if classical music could get rid of that it would be good. It’s an uphill battle.”

Does he think classical music can portray itself as being slightly removed? “I would think only a small percentage of musicians would want to exclude anybody. This whole idea of clapping between the movements, I find it fine – but some people are horrified by it, and I think that’s ridiculous.” So is it less the musicians but more the audiences? “You could say it destroys continuity, but Mozart and Beethoven had plenty of breaks between movements. I think most musicians would welcome it. I don’t stand up when it happens but I acknowledge it with a nod of the head and a smile, for sure. When I was young I went to some Indian concerts with Ravi Shankar, and during the concert people were shouting but not loudly. I asked for the translation and they were saying, “to this there is no answer”. That is such a wonderful response to a turn of phrase!”

The Complete Philips Recordings by Stephen Kovacevich is out now as a box set – and is available to buy from the Universal music store here