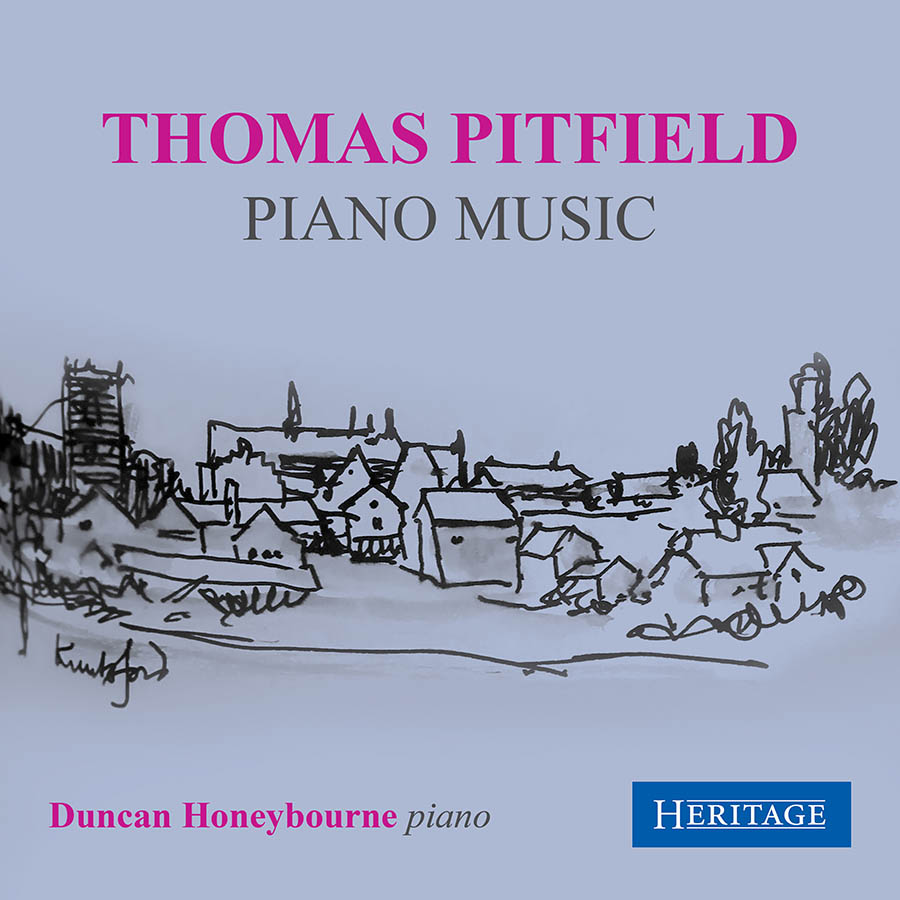

Thomas Pitfield

Toccata (1953)

Solemn Pavane in F minor (1940)

Circle Suite (1938)

Capriccio (1932)

Diversions on a Russian Air (1959)

Novelette no.1 in F major (1953)

Bagatelles – no.1 in E flat major (1950); no.2 in C major (1952); no.3 in F major (c1995)

Impromptu on a Tyrolean Tune (1957)

Two Russian Tunes (1948)

Sonatina no.2 (c1990)

Five Short Pieces (1932)

Prelude, Minuet and Reel (1932)

Little Nocturne (c1985)

Humoresque (1957)

Homage to Percy Grainger (1978)

Cameo and Variant (1993)

Duncan Honeybourne

Heritage Records HTGCD132 [68’40”]

Producer / Engineer Paul Arden-Taylor

Recorded 7-8 September 2024 at Wyastone Concert Hall, Wyastone Leys, Monmouth

Reviewed by Richard Whitehouse

What’s the story?

Heritage continues its coverage of Thomas Pitfield (1903-99), following a reissued volume of chamber music (HTGCD210)) with this well-rounded and representative overview of his piano output, performed with his customary flair and conviction by Duncan Honeybourne.

What’s the music like?

The programme launches in fine style with a Toccata whose sheer rhythmic incisiveness and unforced joie de vivre makes it an ideal encore, and to which the pensive understatement of Solemn Pavan affords pertinent contrast. Written as homages to (and likely evocations of) a close-knit group of musical colleagues, The Circle Suite draws on Baroque dance forms in characterful and always personable terms; while the Capriccio underlines that, throughout his composing, Pitfield allied a deft pianistic technique to a highly appealing musical voice.

Centred on a Russian folksong ‘The Blacksmith’, no doubt conveyed to the composer by his Russian wife, Diversions on a Russian Air packs a diverse range of variants into its modest duration, while the Novelette (at 4’36’’ the longest single item here) unfolds as a rumination audibly in the English ‘pastoral’ tradition. Although they were not written concurrently, the Three Bagatelles amount to an effective sequence – their respectively nonchalant, capering then genial demeanours evoking more than a touch of early 20th century French influence.

The Central European-ness of Impromptu on a Tyrolean Tune makes it surprising this lively tune was encountered in a collection housed at a stately home in Chesire, while Two Russian Tunes comprise a playful ‘Nursery Song’ and plaintive ‘Cossack Cradle Song’. Actually, the third of three such works, the Second Sonatina separates its lively Allegro and rumbustious Finale with a ‘Threnody’ as finds the composer at his most confiding, whereas the engaging Five Short Pieces are pithy miniatures whose pedagogical function is anything but didactic.

Prelude, Minuet and Reel was Pitfield’s earliest success and has (rightly) retained a degree of popularity through its melodic insouciance and rhythmic verve. From among the remaining four pieces, Little Nocturne is most likely an intimate reflection from its composer’s old age, while Humoresque contrasts its expected levity with a surprisingly plangent middle section. Homage to Percy Grainger is a ‘take off’ idiomatic and engaging, while the alternate poise then suavity of Cameo and Variant rounds off this collection in the most disarming fashion.

Does it all work?

It does, accepting those formal and expressive limits within which Pitfield operated. For all that his performers comprised a significant roster of pianists (among them John Ogdon and John McCabe), this is music written for the composer’s pleasure and it eschews profundity without thereby lacking in depth. That he was invited to record this selection by the Pitfield Trust and researched the manuscripts at Manchester’s RNCM says much for Honeybourne’s dedication to the Pitfield cause, reinforced with playing of unfailing perception and finesse.

Is it recommended?

It is and not least as these pieces, few of them previously recorded, offer much of interest to performers and listeners alike. John Turner contributes extensive notes while Honeybourne adds his own observations, enhancing a release that warrants the warmest recommendation.

Listen / Buy

You can read more about this release and explore purchase options at the Heritage Records website

Published post no.2,577 – Friday 27 June 2025