Stephen Waarts (violin), City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra / Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla

Brahms Violin Concerto in D major Op.77 (1878)

Weinberg Symphony no.5 in F minor Op.76 (1962)

Symphony Hall, Birmingham

Wednesday 11 June 2025

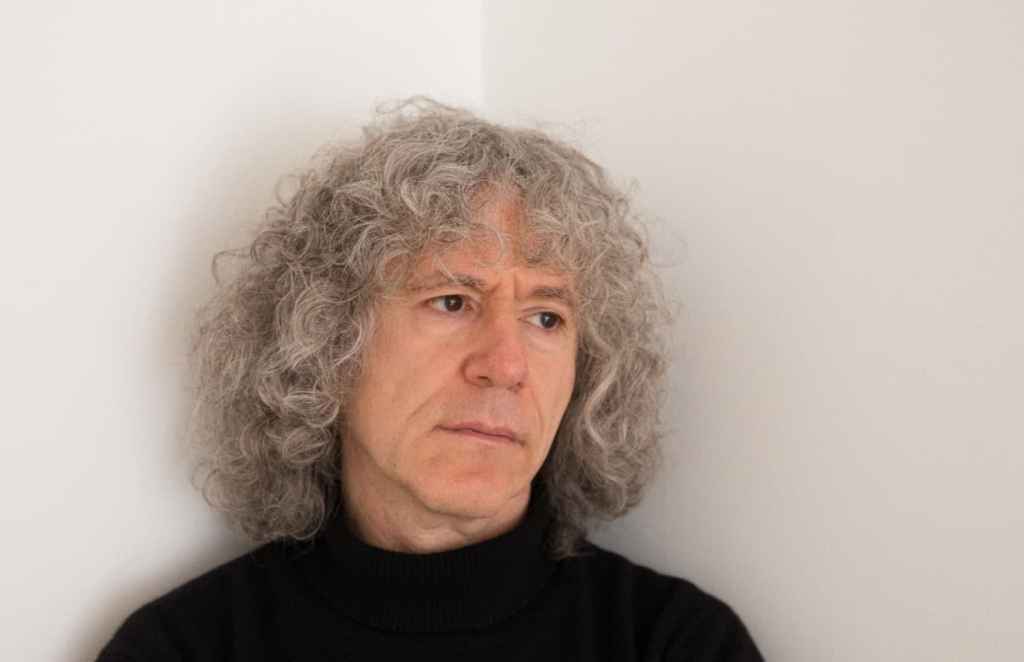

Reviewed by Richard Whitehouse Picture of Stephen Waarts (c) Maarten Kools

Seriously disrupted as it was by the pandemic and attendant lockdowns, the period of Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla as music director of the City of the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra (2016-22) was a successful one, especially in terms of bringing unfamiliar music to the orchestra’s repertoire.

Not least that by Mieczysław Weinberg, his Fifth Symphony tonight receiving only its second UK hearing, almost 63 years after Kiril Kondrashin and the Moscow Philharmonic had given it at the Royal Festival Hall while on tour. Weinberg was unable to attend and the performance attracted minimal comment, but the Fifth is arguably the greatest among his purely orchestral symphonies – a work whose size and scope had merely been hinted at by its predecessors. Six decades on and those qualities confirming its significance then still ensure its relevance today.

The influence of Shostakovich’s Fourth Symphony, written over a quarter century earlier but premiered just months before, has often been noted but whereas this piece is inclusive to the point of overkill, Weinberg’s Fifth has a formal rigour and expressive focus as could only be that of full maturity. Not least in the moderately-paced opening Allegro, its content deriving from the pithy motifs on lower strings and trumpet heard against oscillating chords on upper strings at the outset, and which builds to a febrile culmination before retreating into agitated uncertainty. MGT has its measure as surely as that of the ensuing Adagio, its threnodic string writing palpably sustained prior to a heartfelt climax; either side of which, woodwind comes into its own in a slow movement comparable to that of Shostakovich’s own Fifth Symphony.

Playing without a pause, the latter two movements consolidate the overall design accordingly. Thus, the scherzo-like Allegro alternates furtive anticipation and barbed anger with a dextrous virtuosity that found the CBSO at its collective best – subsiding into a finale whose Andantino marking rather belies the purposefulness with which it elaborates on earlier ideas as it builds towards a searingly emotional apex. Once again, however, the music winds down into a coda whose rhythmic pulsing underpins resigned solo gestures at the close of this eventful journey.

Whether or not Brahms’s Violin Concerto was an ideal coupling, it certainly received a most impressive reading by Stephen Waarts (above). Winner of the 2014 Yehudi Menuhin International and 2015 Queen Elizabeth competitions, this was his debut with the CBSO but there was no lack of rapport – not least an imposing first movement whose technical challenges were assuredly negotiated and with a rendering of the Joachim cadenza that integrated it seamlessly into the overall design. Waarts’ interplay with woodwind in the Adagio was never less than felicitous, then the finale pivoted deftly between panache and insouciance on its way to a decisive close. MGT was as perceptive an accompanist as always, with an encore of the opening ‘L’Aurore’ movement from Eugène Ysaÿe’s Fifth Solo Sonata an appropriate entrée into the second half.

Ultimately, though, this concert was about MGT’s continued advocacy of Weinberg as of her association with the CBSO. Good news that the Fifth Symphony has been recorded for future release by Deutsche Grammophon, so enabling this fine performance to be savoured at length.

For details on the 2025-26 season, Orchestral music that’s right up your street!, head to the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra website. Click on the names to read more about soloist Stephen Waarts and conductor Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla, or composer Mieczysław Weinberg

Published post no.2,564 – Saturday 14 June 2025