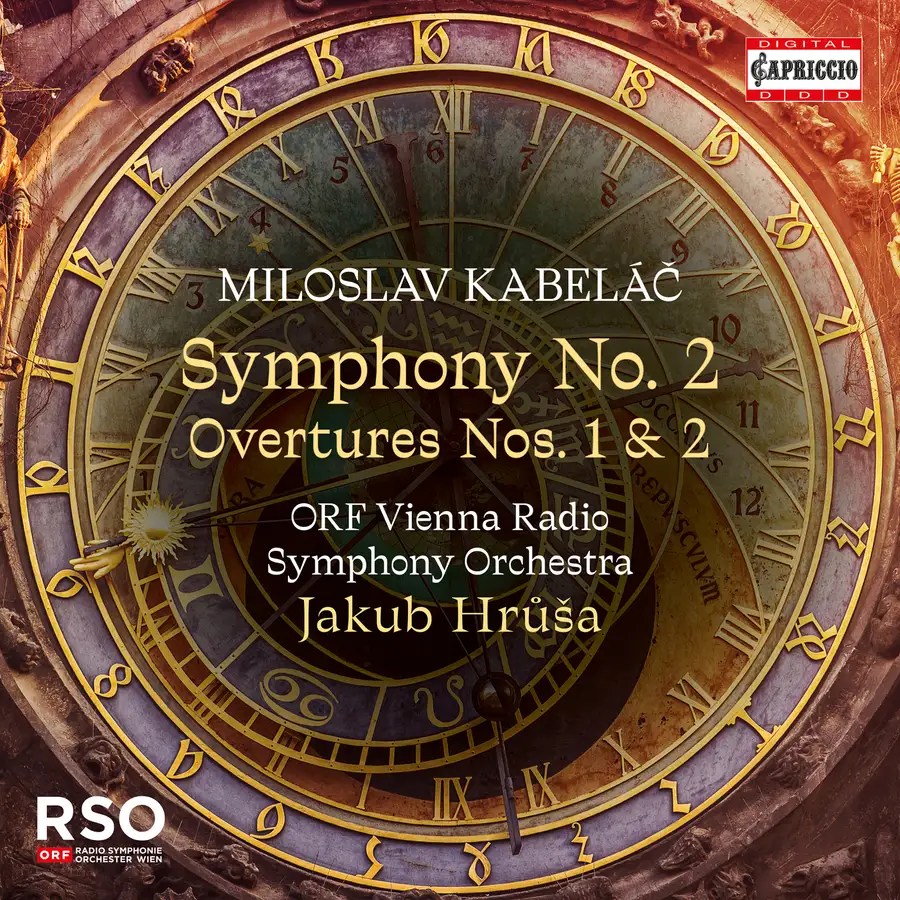

ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra / Jakub Hrůša

Kabeláč

Symphony no.2 in C major Op.15 (1942-6)

Overture no.1 Op. 6 (1939)

Overture no.2 Op.17 (1947)

Capriccio C5546 [54’51’’]

Producer Erich Hofmann Engineer Freidrich Trondl

Recorded 14-16 June 2023 (Symphony), 17 June 2024 (Overtures) at Konzerthus, Radio Kulturhaus, Vienna

Reviewed by Richard Whitehouse

What’s the story?

Capriccio continues its exploration of paths less travelled with a collection of early orchestral works from the Prague-based composer Miloslav Kabeláč (1908-79), all persuasively realized by the ORF Symphony Orchestra of Vienna while authoritatively conducted by Jakub Hrůša.

What’s the music like?

Although his output made little headway outside his native Czechoslovakia over his lifetime, with its dissemination subject to considerable restrictions imposed by those authorities either side of the Dubček era, Kabeláč has belatedly been recognized as a major figure from among the European composers of his generation. The three pieces featured here give only a limited idea of those radical directions that his music subsequently took, though a distinct personality is already evident such that they afford a worthwhile and rewarding listen in their own right.

His first such work for full orchestra, the Second Symphony occupied Kabeláč throughout the latter years of war and into a peace whose promise proved but fleeting. Uncompromising as a statement of intent, the first of its three movements unfolds from an imposing introduction to a sonata design as powerfully sustained as it is intensively argued. Beginning then ending in elegiac inwardness, while characterized by an eloquent theme for alto saxophone, the central Lento builds to a culmination of acute plangency. It remains for the lengthy finale to afford a sense of completion, which it duly does with its methodical yet impulsive course towards an apotheosis whose triumph never feels contrived or overbearing. Successfully heard in Prague then at the ISCM Festival in Palermo, the piece endures as a testament to human aspiration.

This recording is neatly and appositely rounded out with the brace of overtures Kabeláč wrote on either side of the symphony (neither of which appears to have been commercially recorded hitherto). Written in the wake of the Nazi’s invasion of Czechoslovakia, the First Overture is a taut study in martial rhythms whose provocation could hardly have been doubted at its 1940 premiere. Eight years on and the Second Overture is no less concise in its form or economical in its thematic discourse, while exuding an emotional impact which doubtless left its mark on those who attended its 1947 premiere and seems the more poignant in the light of subsequent events. Kabeláč was to write more searching orchestral pieces in those decades that followed, yet the immediacy and appeal of his earlier efforts is still undimmed with the passage of time.

Does it all work?

Yes, owing not least to the excellence of these accounts. While he has not previously recorded the composer, Hrůša directed a memorable performance of Kabeláč’s masterly orchestral work Mystery of Time in London some years ago and he conveys a tangible identity with his music. Those who have the excellent Supraphon set of Kabeláč symphonies (SU42022) need not feel compelled to acquire this release, but those who do will hear readings of this uncompromising music which are likely to remain unsurpassed in their authoritative playing and interpretation.

Is it recommended?

Very much so. Recorded sound could hardly be bettered for elucidating the frequently dense but never opaque orchestral textures, and Miloš Haase pens an insightful booklet note. Those yet to acquire Capriccio’s overview of Kabeláč’s chamber music (C5522) are urged to do so.

Listen / Buy

You can hear excerpts from the album and explore purchase options at the Presto website, or you can listen to the album on Tidal. Click to read more about the ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra and conductor Jakub Hrůša – and for more on composer Miloslav Kabeláč.

Published post no.2,793 – Monday 9 February 2026