Published post no.2,507 – Friday 18 April 2025

Tag Archives: Johann Sebastian Bach

New music – Francesco Tristano: Bach – English Suite no.2 in A minor: Prelude (naïve)

adapted slightly from a press release received earlier today:

After a special release in Japan, Bach: The 6 English Suites by Francesco Tristano will be released globally on May 23rd on naïve, a label of Believe Group, under his imprint intothefuture. As a first glimpse into this highly anticipated album, the Prelude from the English Suite no.2 is released today.

Following Bach: The 6 Partitas, the new recording continues Tristano’s deep exploration of J.S. Bach’s keyboard works. With his distinctive style, he brings a dynamic and immersive interpretation, capturing the rhythmic vitality and expressive depth of these suites, composed in the 1710s. Listen here:

Published post no.2,478 – Wednesday 19 March 2025

In appreciation – György Kurtág at 99

by Ben Hogwood Picture of György Kurtág (c) Filarmonia Hungaria

This is a post in honour of the remarkable composer György Kurtág, celebrating his 99th birthday today.

You can read about his work with baritone Benjamin Appl in an interview published on Arcana last week, but to get some appreciation of Kurtág’s remarkable music, here are a few pointers:

It is perhaps a bit restrictive trying to listen to Kurtág’s music via a YouTube link, so if you can find a widescreen system to play Grabstein für Stephan on then I fully recommend it. Following the score will show just how imaginative his orchestration is, and how compressed and concentrated the music becomes.

Meanwhile the Microludes, for string quartet, encapsulate Kurtág’s economical and pinpoint style, pieces whose every move and aside is critical to the whole.

One of my favourite live experiences was watching Kurtág and his now late wife Márta play exquisite duets at the Wigmore Hall for the composer’s 80th birthday. It was like eavesdropping on a private conversation between two intimately connected souls, no more so than when they were playing Kurtág’s own arrangements of J.S. Bach:

Published post no.2,450 – Wednesday 19 February 2025

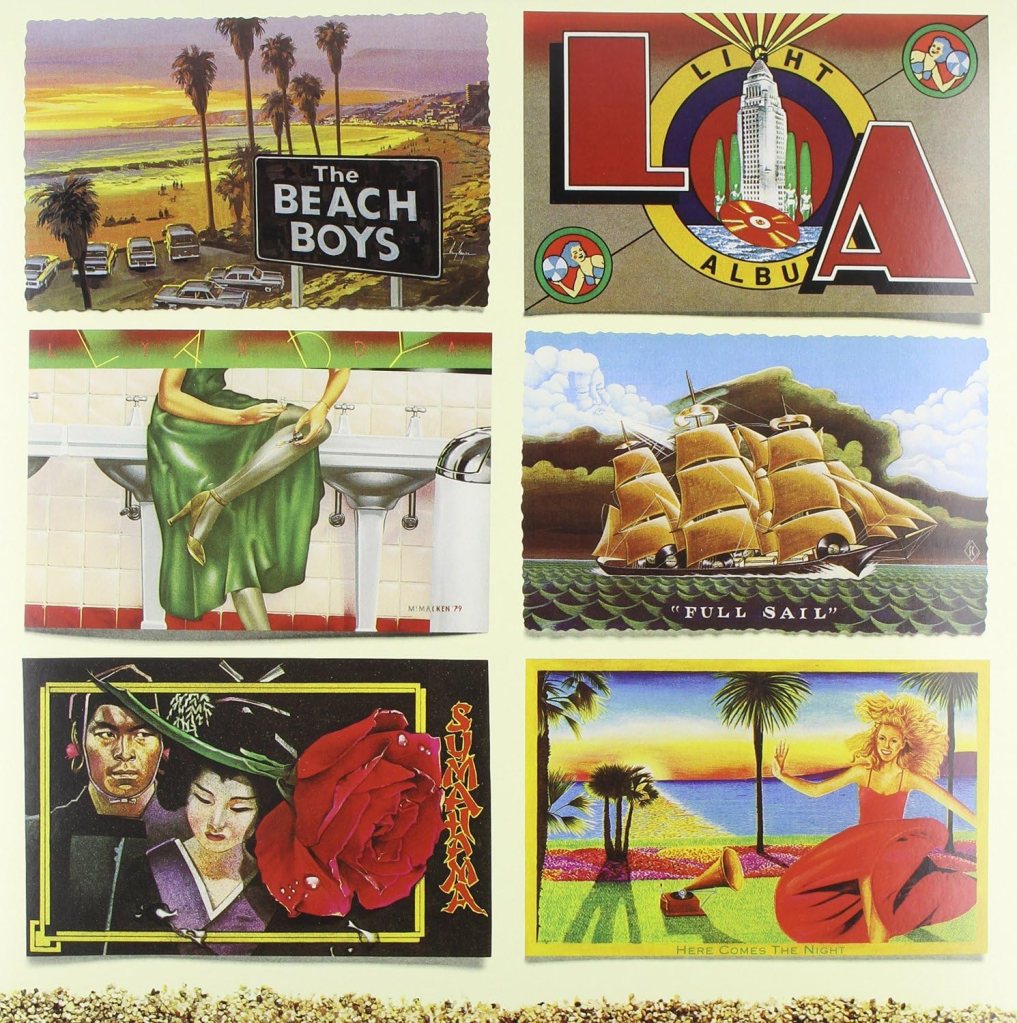

The Borrowers – The Beach Boys: Lady Lynda

by Ben Hogwood

What tune does it use?

A choral piece by Johann Sebastian Bach, called Jesu Bleibet Meine Freude (Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring). It is the tenth movement of his cantata Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben (Heart and mouth and deed and life), written early in Bach’s time in Leipzig, thought to have been in 1723. The melody, however, is understood to have been written by Johann Schop, with Bach providing the harmonisation.

The song itself was written by Beach Boys co-founder Al Jardine, paying tribute to his wife Lynda – with a co-credit also given to keyboard player Ron Altbach. Jardine sings the main vocals, with a large ensemble of session musicians given credit at the song’s Wikipedia page.

How does it work?

The song begins with a note-for-note reproduction of the Bach / Schop melody, with the harpsichord adding a metallic brightness to the thick string sound. Then Jardine starts to play around with the speed of Bach’s work, making the transition to the full-blown Beach Boys sound reasonably seamless, with the addition of some woozy syncopations.

The song has the Beach Boys’ characteristically sunny sound, but there is a certain flatness to its delivery, perhaps belying the band’s fraught relationship at the time and even foretelling the fate of Al and Lynda’s marriage.

That said, it is a bright and relatively positive song, its dappled textures and syncopations presenting Bach’s work in a new and imaginative light.

What else is new?

Lady Lynda was the third single from the Beach Boys’ relatively unsuccessful album L.A. (Light Album), released in the spring of 1979. In a streamlined radio edit, with the introduction removed, it reached no.6 in the UK singles chart.

It was however recast when Jardine and his wife divorced, pointing towards a different Lady (the Statue of Liberty) and becoming Lady Liberty instead.

Published post no.2,406 – Thursday 9 January 2025

In concert – Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment: Bach Brandenburg Concertos @ Queen Elizabeth Hall

Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment

J.S. Bach

Brandenburg Concertos:

no.1 in F major BWV1046 (dir. Huw Daniel)

no.3 in G major BWV1048 (dir. Margaret Faultless)

no.5 in D major BWV1050 (dir. Margaret Faultless)

no.4 in G major BWV1049 (dir. Huw Daniel)

no.6 in B flat major BWV1051 (dir. Oliver Wilson)

no.2 in F major BWV1047 (dir. Rodolfo Richter)

Queen Elizabeth Hall, London

Wednesday 13 November 2024

Reviewed by Ben Hogwood Pictures (c) Mark Allan

The music of Bach proves a great source of consolation for many in uncertain times, and the underlining feeling from this packed concert was that the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment had offered just that, deep into their tour of the great master’s complete Brandenburg Concertos.

The six concertos, written for a variety of instrumental ensembles, were published just over 300 years ago in 1721 and sent to Christian Ludwig, Margrave of Brandenburg. In a crowded field, they have become one of Bach’s best-loved groups of works, and although they were not designed to be played together they respond extremely well to a concert such as this.

It is difficult to imagine a better set of performances than those given by the OAE, playing without a conductor in the spirit of the compositions, assigning the direction of each concerto to the uppermost string player. The program was introduced with a spark by violinist Margaret Faultless, whose enthusiastic demeanour set the tone for the evening. As the notes of the Brandenburg Concerto no.1 in F major lifted off the page Bach’s inspiration was immediately apparent, like walking into a room of animated conversation. The horns of Ursula Paludan Monberg and Martin Lawrence were front and centre, pointed aloft in a necessary but striking pose. The balance between the 13 players was ideal, not just in the busy first movement but in the emotive Adagio, led by the beautiful tones of oboe trio Clara Espinosa Encinas, Sarah Humphrys and Grace Scott Deuchar. Yet the horns took centre stage, powering the bright Allegro, before a perky series of Menuetto dances were bisected by a bracing second trio.

One of the many joys of the concert was the different sonorities of each piece, which changed to nine string instruments for the Brandenburg Concerto no.3 in G major. This had the requisite spring in its step for the quicker outer movements, especially the jovial dialogue of the third. Meanwhile the ensemble elaborated on Bach’s two written chords that make up the slow movement, where the focus was on violin (Faultless) and harpsichord (Steven Devine) Their tasteful improvisations were an ideal foil.

Completing the first half was the Brandenburg Concerto no.5 in D major, in effect an early keyboard concerto. The seven players were positioned closer to the audience, allowing greater intimacy and the chance to appreciate some of the wondrous sequences in the first movement. Taking the lead here were flautist Lisa Beznosiuk, who recorded the concertos with the orchestra back in 1987, alongside Faultless and Devine. They delivered a sublime Affettuoso second movement, a moment of reflection from the fast movements where Devine was a revelation, his virtuosic brilliance never too showy even in the trickiest of cadenzas.

To begin the second half of the concert the mellow sonorities of the recorders took the lead in the Brandenburg Concerto no.4 in G major, with beautiful clarity achieved by Rachel Beckett and Catherine Latham. Violinist Huw Daniel mastered the busy figuration of his part with considerable flair, while the poise of the accompanying ensemble was consistently satisfying. This concerto is deceptively forward looking, with pointers towards Beethoven in the slow movement, which here benefited from the weighty support of viola da gamba (Richard Tunnicliffe) and double bass (Cecilia Bruggemeyer), both ever presents through the evening. The pugnacious finale, with one of Bach’s many earworms, was great fun in the hands of these nine players.

The colours darkened appreciably for the Brandenburg Concerto no.6 in B flat major, whose highest instrument is the viola. Bach’s scoring here is remarkably inventive, and was brought to life as Oliver Wilson led a fluent account of the first movement. The violas showed their versatility as melody instruments in the reduced scoring of the Adagio, reduced from seven to four players and enjoying its elegant dance-like figurations, before the syncopations of the Allegro were winningly delivered.

Finally the Brandenburg Concerto no.2 in F major was a suitably upbeat piece on which to finish, with soloist David Blackadder – having waited an hour and a half to play – enjoying his moment on stage. He made the trumpet line look – and sound – straightforward, when with this instrument it is anything but! Again the balance was carefully wrought, so that the intricate violin contributions of director Rodolfo Richter could be clearly heard. A lightness of touch from the 11 players brought the phrasing of the Andante to life, with some typically spicy harmonies stressed, before the brilliant colours of the closing Allegro assai, and a celebratory closing statement.

It was a treat to hear the six Brandenburg Concertos presented in this way, a reminder that – in the words of Huw Daniel – these concertos deserve to be the centre of attention. The humming of the audience afterwards was testament to their lasting appeal, 300 years on.

You can listen to the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment’s recordings of the Brandenburg Concertos from 1987-88 for Virgin Classics below:

Published post no.2,362 – Thursday 14 November 2024