Beethoven’s Leonore as designed for the Wiener Staatsoper, 2020

Leonore, opera in three acts (1804-05, Beethoven aged 34)

Libretto Jean Nicolas Bouilly, trans. Joseph Sonnleithner

Duration 138′

by Ben Hogwood

Background, Synopsis and Critical Reception

“Probably nothing has caused Beethoven so much grief as this work, whose value will be fully appreciated only in the future”.

The words of Stephan von Breuning to Franz Wegeler in Bonn, talking about Beethoven’s first opera Leonore, which did indeed bring a great deal of strife for its composer in the lead-up to the premiere in November 1805.

The libretto was relatively new, written in the late 1790s by Jean Nicolas Bouilly, the administrator of a French department near Tours during the Reign of Terror. Lewis Lockwood gives an excellent back story to Leonore’s construction. He writes that ‘it was widely accepted that during Bouilly’s governance an episode resembling that of the opera plot had actually taken place’…where ‘a woman disguised as a young man had worked her way into her husband’s prison and freed him from his unjust captivity. Thus, if the take were true, Bouilly himself would have been the minister who liberated the prisoner, and so the libretto seemed to commemorate not only actual heroism but the author’s own benevolence amid the frightening atmosphere of France in those years.’

The opera is set in the prison. The first act is conducted at ground level, where the prisoners take in the rarified air on their rare visits above ground, and where Leonore, disguised as Fidelio, has arrived to try and rescue her beloved Florestan. Immediately she becomes the object of Marcellina’s affections, which she eventually repels. In this process we are introduced to Rocco, a peasant voiced by a fulsome baritone who helps Leonore greatly.

The two levels below ground are reserved for the prisoners, The second act brings them to the fore, as Leonore gets closer to freeing her beloved, with memorable moments including the quartet Mir ist so wunderbar and the Prisoners’ Chorus. The third and final act begins in the dungeon where Florestan has been chained to the wall for two years, freezing and starving. He takes centre stage at the start, his pain all too evident for the audience in the aria Gott, welch Dunkel hier. Liberation is at hand, however – Florestan seeing Leonore as an angel sent to rescue him. The finale celebrates her bravery.

Rather confusingly, Beethoven wrote four overtures for Leonore / Fidelio. The first one to be used was Leonore no.2, which was used for this version of Leonore. The subsequent three versions work in different introductions for Florestan’s aria, while the Fidelio overture itself – written for the 1814 staging – is wholly different.

Two composers had already set the libretto to music. The second, Ferdinando Paer, aroused Beethoven’s interest and competitive edge. Because Paer had already named his version Leonore, Beethoven titled his Fidelio, or Conjugal Love. He hooked up with Joseph Sonnleithner, a prominent musical figure in Vienna, who translated the libretto – on which Beethoven began work in January 1804. At that point he only wanted the ‘poetical part’ of the libretto to be translated, and an exchange between the two reveals that his plans were already in place to stage the work in June 1804. leading up to the premiere in November 1805, which took place under the shadow of Napoleon’s anticipated invasion of Vienna – and was indeed attended by a large number of French army officers. Further attempts at staging in Berlin and Prague were unsuccessful, before Beethoven revised the opera for a production in Vienna in 1814, renaming it Fidelio.

As Jan Swafford explains in an absorbing biography chapter about Leonore, writing vocal music could be a struggle for Beethoven. “He always had more trouble writing vocal music than instrumental”, Swafford writes, referring to the sketchbook for Leonore where there are 18 different beginnings to Florestan’s aria In des Lebens Frühlingstagen and a mere ten for the chorus Wer ein holdes Weib. That didn’t mean Beethoven wasn’t any good at it, but the process of getting the right notes on the page was a painful experience.

The results, however, have been revelatory. Lewis Lockwood describes a work that “has resonated through two centuries as a celebration of female heroism”. In a candid booklet note for his recording of Leonore on Deutsche Grammophon, John Eliot Gardiner notes how “for sheer simplicity and directness of utterance, and for the way he imbues his orchestral set-pieces and accompaniments with dramatic life and emotional intensity, Beethoven has no peer. His single opera has a unique appeal, and a magic very much of its own – especially in its first version, the Leonore of 1804-05, where his ideas, while sometimes crude, are at their most radical.” Later, he declares that “while as a musician I can easily succumb to the sheer beauty of the new music written for Fidelio, nothing, I find, can compare with Beethoven’s original response to his material in 1805.”

Thoughts

In spite of Beethoven’s difficulties, and a compositional practice where he had to grind out many of the results, Leonore is a thoroughly absorbing drama from start to finish. Right from the call to arms of the overture the listener is gripped, the stark outlines immediately setting a tense atmosphere which only occasionally lets up when more tender love is expressed.

The use of a narrator between scenes does not check the flow of the drama – if anything it provides helpful points of context. Without the information provided by Beethoven scholars, would we have known of the difficulties he experienced in composing? As John Eliot Gardiner says, the ‘dramatic life and emotional intensity’ are always there, with relatively little padding in the plot.

What helps, too, is how easily Beethoven moves between solo arias, duets, trios and quartets – and even in the latter the use of many voices does not stop him from getting clarity. The first quartet in Act 1, Mir ist so wunderbar, is beautifully woven in together – while on the solo front, Ha! Welch is a brisk aria, led from the front by Pizarro who is in jubilant mood. Beethoven is certainly not afraid of putting his foot on the accelerator when needed.

Interestingly the operatic influences – to this ear at least – are less from his vocal training with Salieri but more from study of Handel. This is the case especially where recitatives and arias are paired, as in the finale to Act 2.

There are some genuinely thrilling moments in Leonore. The flurry of activity through the Act 2 duet between Pizarro and Rocco (Jetzt, Alter, hat es Eile!) shows the urgency of which Beethoven is capable. Auf Euch nur will ich bauen, led by Pizarro is an exhilarating trio, punchy and red blooded with a shiny brass coating. Countering this is the bleak, vivid word painting at the start of Gott! Welch dunkel, the extended scene where Florestan is down in the dungeon. It is a stark piece of writing and incredibly affecting with orchestra and emotion stripped bare, Florestan’s pain revealed for all to hear in F minor, one of Beethoven’s ‘tragic’ keys. Consolation, however, is found in the love for Leonora, expressed in a tender theme whose radiance is all the more revealing in this setting. High drama follows in the quartet, the exclamations brilliantly managed, and the top ‘C’ soprano near end of Ich Kann mich noch nicht fassen carries maximum impact.

The opera flows very naturally from one section to the next. Although this is an opera with a female hero there are a lot of steely lines for men at the start of Act 2 – none more so than the explosive arrival of Pizarro with his declamation that Ha! Welch ein Augenblück (Ha, the moment has come when I can wreak my vengeance!) Marcellina and Leonora arrive to redress the balance in a brightly cast C major. Ach brich noch is a standout aria, with sonorous horns for company, written in a higher register that looks forward to Weber and beyond. While Act 1 is described as more ‘domestic’ is it nonetheless a satisfying experience, with the arias for Marcellina and Rocco hardly throwaway. The latter’s first aria, where “if you haven’t gold as well, happiness is hard to find” is memorable.

Yet while these moments are high points, nothing quite carries the impact of The Prisoners’ Chorus. This is the dramatic apex of the work, wide-eyed wonder spreading from the jailed forces as their strength comes to the fore. Then, as Leonore learns of the likelihood of marriage, there is a breathless joy. The other many high points are the prisoners, ‘filled with loyalty and courage’ at the rousing end to Act 2, and the reveal of Leonore to Florestan, with the oboe’s involvement especially poignant. The finale is full of incident, the music eventually shifting to a pumped-up C major for a triumphant finish.

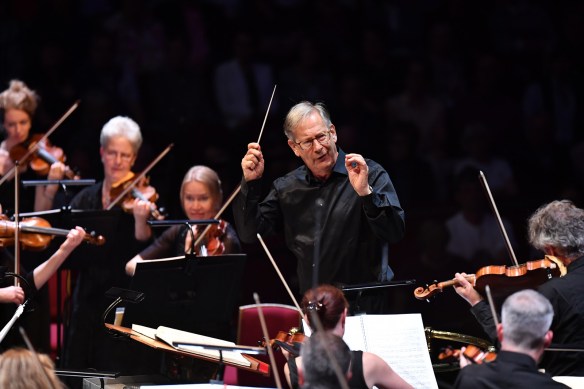

Beethoven experienced a great deal of bad fortune in the realisation of Leonore, and the opera has since proceeded under a cloud. In fact, it is only in the last 30 years or so that it has regained anything of its stature, thanks to notable recordings from John Eliot Gardiner and René Jacobs. Both these esteemed conductors have seen the qualities in the music, and how Beethoven – contrary to the opinion of some – has proved to be a great opera composer.

Recordings used

Hillevi Martinpelto (Leonore), Kim Begley (Florestan), Franz Hawlata (Rocco), Matthew Best (Don Pizarro), Christian Oelze (Marzelline), The Monteverdi Choir, Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique / John Eliot Gardiner (DG Archiv)

Marlis Petersen (Leonore), Maximilian Schmitt (Florestan), Dimitry Ivashchenko (Rocco), Johannes Weisser (Pizarro), Robin Johannsen (Marzelline), Freiburg Baroque Orchestra / René Jacobs (Harmonia Mundi)

Those two recordings I mentioned are both cut and thrust experiences. René Jacobs provides a leaner orchestra and much faster tempo choices, which plays to the speed of Beethoven’s creativity. For John Eliot Gardiner Matthew Best is a superbly malevolent Pizarro. Both have superb soloists – and rather than choose a favourite I would merely opt for both! You can listen on the links below:

Also written in 1805 Cherubini Faniska

Next up Leonore Overture no.2 Op.72a

Inevitably it is the orchestra which so often steals the limelight in a work by Berlioz, and the Orchestre Revolutionnaire et Romantique accordingly rose to the challenge. Of course, any performance of this music on ‘authentic’ instruments must contend with his assertions that the development of instrument-making and instrumental practice (notably within Germanic territories) was a necessary one. That said, he may have been reconciled to those limitations had his work been rendered with such timbral brilliance and intonational accuracy as here.

Inevitably it is the orchestra which so often steals the limelight in a work by Berlioz, and the Orchestre Revolutionnaire et Romantique accordingly rose to the challenge. Of course, any performance of this music on ‘authentic’ instruments must contend with his assertions that the development of instrument-making and instrumental practice (notably within Germanic territories) was a necessary one. That said, he may have been reconciled to those limitations had his work been rendered with such timbral brilliance and intonational accuracy as here.