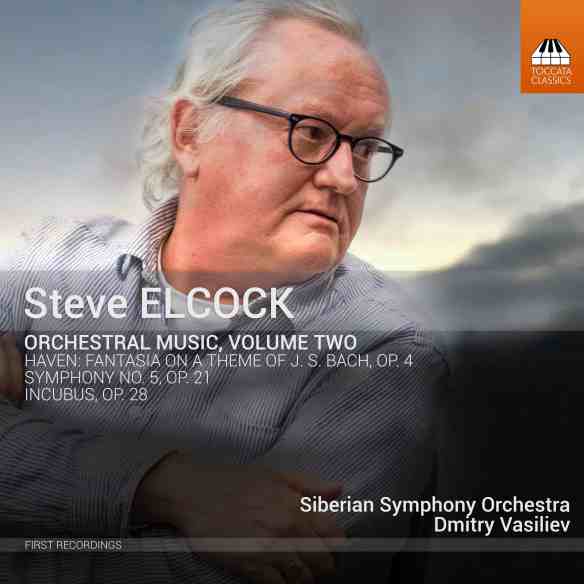

Steve Elcock

Incubus Op.28 (2017)

Haven: Fantasia on a Theme by J.S. Bach Op.4 (1995, rev. 2011-17)

Symphony no.5 Op.21 (2014)

Siberian Symphony Orchestra / Dmitry Vasiliev

Producer/Engineer Sergei Zhiganov

Recorded 8-12 July 2019, Philharmonic Hall, Omsk

Toccata Classics TOCC0445 [77’20”]

Reviewed by Richard Whitehouse

What’s the story?

Toccata Classics continues its coverage of Steve Elcock (b1957) with this second instalment of orchestral music – dominated by the Fifth Symphony with provocative allusions to its most famous predecessor, together with shorter yet distinctive pieces from either end of his output.

What’s the music like?

Although it marks a return to the four-movement format of his first two such works, the Fifth Symphony is hardly conventional in formal or expressive follow through. As with the almost contemporaneous Fifth by the late Christopher Rouse, the presence of that archetypal ‘No. 5’ feels undeniable – even more so given Elcock’s explicit referencing at the start of each outer movement; a head-on approach hardly less confrontational than that with Beethoven Nine in Tippett’s Third Symphony a half-century ago. In all other respects, Elcock goes entirely his own way: the visceral charge of that beginning quickly subsides into an opening movement whose restive searching seems becalmed emotionally while not tonally, as the music strives increasingly to regain its initial energy before relapsing into a mood of pervasive desolation.

The next two movements unfold without pause as a contrasting duality. As its title suggests, the Ostinato builds explosive impetus over a remorseless rhythmic motto that climactically implodes to leave a musing clarinet melody as expands into the ensuing Canzonetta. Less a slow movement than extended intermezzo, what might have brought a return to the earlier sombreness rather assumes a more compassionate aura that makes possible the final Allegro. Comparable to the first movement in its scale, this unfolds as a sonata design of unflagging dynamism whose twin themes are drawn into a process of continuous development on route to a peroration which, though it could hardly evince the triumph of Beethoven, is never less than affirmative in its bringing the work decisively and, moreover, demonstrably full circle.

A notable achievement, then – less ruggedly distinctive if ultimately more cohesive than the Third Symphony (recorded on TOCC0400), and evidently a statement with which to reckon. It is preceded here by two pieces that further attest to the consistency of Elcock’s underlying vision. Haven: Fantasia on a Theme by J.S. Bach takes the Sarabande from the First Violin Partita as basis for a series less of variations than of paraphrases such as pass from nostalgia, through militaristic brutality, to renewed concord with the theme newly explicit at the close. Derived from a recent string quartet, Incubus is a study in nocturnal imaginings – ostensibly the result of insomnia – which seems predictable only in its marshalling a disparate range of ideas into a taut ‘curtain raiser’ whose outcome is the more telling for being so unexpected.

Does it all work?

It does. Just occasionally taxed in those more demonstrative passages, the Siberian Symphony Orchestra otherwise yields little to the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic as to the conviction of its playing, with Dmitry Vasiliev demonstrating an absolute grasp of Elcock’s combative musical vision.

Is it recommended?

It is. Orchestral sound has commendable heft and perspective, while Francis Pott’s extensive annotations situate all three pieces within an appropriately wide context. Hopefully Elcock’s Fourth Symphony will feature on the next volume in what is an absorbing and valuable series.

Listen

Buy

For further information, audio clips and purchase information visit the Toccata Classics website. For more on Steve Elcock you can visit the composer’s website