Caplet En regardant ces belles fleurs

Milhaud L’innocence Op. 10/3

Hahn À Chloris

Ravel arr. Stravinsky Trois poèmes de Stéphane Mallarmé M64

Auric Trois Interludes: Le pouf.

Ropartz La Route

Durey L’Offrande lyrique Op. 4

Saint-Saëns Petit main Op.146/9

Fauré Il m’est cher, Amour, le bandeau, Op. 106/7

Chaminade Je voudrais être une fleur

Debussy Trois poèmes de Stéphane Mallarmé L127

Satie ed. Dearden Trois Poèmes d’Amour

Lili Boulanger Clairières dans le Ciel: Vous m’avez regardé avec votre âme

Grovlez Guitares et mandolines

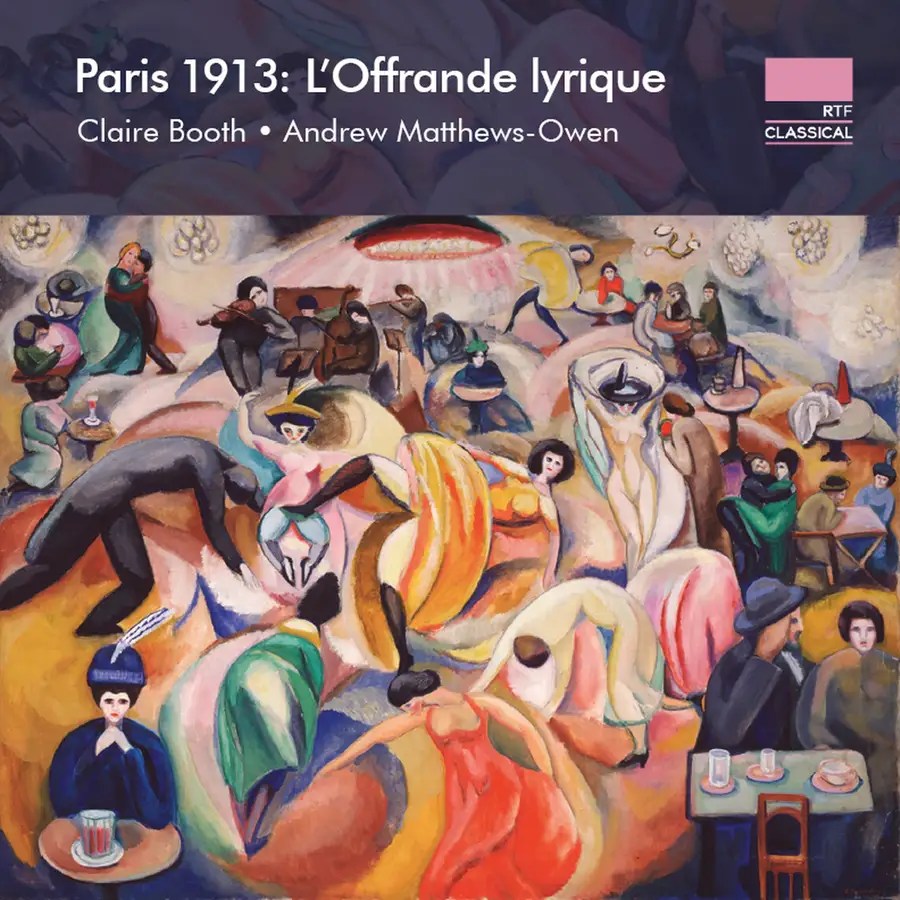

Claire Booth (soprano), Andrew Matthews-Owen (piano)

Nimbus RTF Classical NI6455 [66’23”] French texts included

Producer & Engineer Raphaël Mouterde

Recorded 11/12 March, 4-6 September 2023 at Wyastone Concert Hall, Monmouth

Reviewed by Richard Whitehouse

What’s the story?

Another enterprising song recital from Claire Booth and Andrew Matthews-Owen, this one focussing on songs that were either conceived, composed or premiered in Paris during 1913 and resulting in an absorbing collection best heard as a diverse while unpredictable totality.

What’s the music like?

Interleaving standalone songs and song-cycles, this recital opens with André Caplet’s take on Charles d’Orléans, its limpid modality highly appealing, then continues with an early song by Darius Milhaud as already demonstrates his distinctive and amusing approach to word-setting, while that by Reynaldo Hahn typifies the teasing charm familiar from his vocal music overall. Maurice Ravel’s triptych to texts by Mallarmé is performed in a version by Stravinsky with its accompanying nonet reduced to piano which, in preserving and maybe even accentuating the music’s questing introspection, represents no mean fete of transcription. Still relatively little known, this certainly deserves to be heard as at least an occasional alternative to the original.

Remembered best as a prolific writer of film scores, Georges Auric had shown a precocious talent for song as is evident in his sensuous setting of René Chalupt. A composer who often wrote on a symphonic scale, Guy Ropartz is heard in a setting of his own verse that amounts to a ‘scena’ in its wide expressive ambit. Interest understandably centres on the eponymous cycle by Louis Durey, a member of Les Six whose increasingly far-left conviction tended to marginalize his creativity yet, as these lucid and empathetic settings of Rabindranath Tagore (as translated by André Gide) confirm, had emerged as a protean talent by his mid-twenties. Hopefully these artists will be encouraged to investigate other of his songs from this period. By contrast, a late song by Camille Saint-Saëns exudes a touching poignancy, while that by Gabriel Fauré typifies the elusiveness of those in his last decade. As is evident here, Cécile Chaminade was a songwriter of style and elegance, then the Mallarmé triptych by Debussy (its first two texts identical to those of Ravel) finds this composer probing the inscrutability of these poems while drawing back from any more explicit intervention. The inscrutability conveyed by Erik Satie’s aphoristic settings (edited by Nathan James Dearden) of his own texts is altogether more playful – after which, the recital continues with a pensive offering by Lili Boulanger, with Gabriel Grovlez’s sultrily evocative setting of Saint-Saëns to finish.

Does it all work?

Yes, given the fascination of this collection taken as a whole and, moreover, the quality of these renditions. Booth is not a singer willing to take the easy option in her interpretations, and so it proves here with singing as fastidious as it is refined, while Matthews-Owen duly instils often deceptively spare accompaniments with understated insight. They contribute a succinctly informative note, but the booklet includes only the French texts with the English translations available at https://rtfn.eu/paris1913/: might it have best the other way round?

Is it recommended?

Very much so. There is much to fascinate even those who consider themselves afficionados of the ‘chanson’, and those who are unfamiliar with much of this repertoire could not have a better means of acquainting themselves with certain of its treasures – hidden or otherwise.

Listen & Buy

For purchase options, you can visit the Ulysees Arts website. For information on the performers, click on the names to read more about Claire Booth and Andrew Matthews-Owen

Published post no.2,466 – Friday 7 March 2025