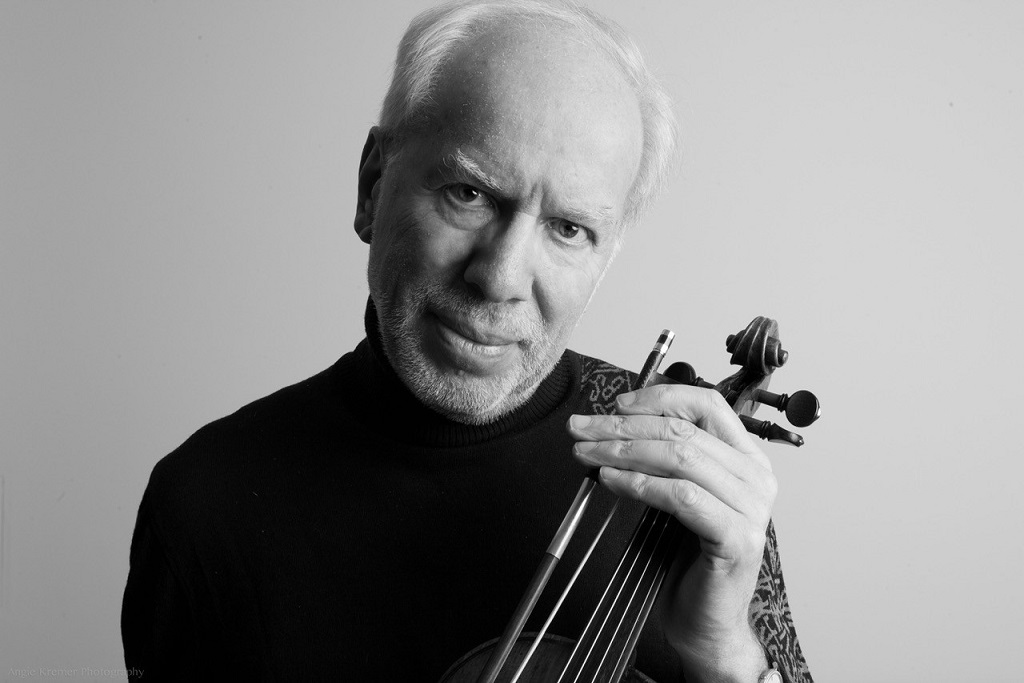

Freddie Jemison (treble), Maria Makeeva (soprano), Gidon Kremer (violin, above), Kremerata Baltica, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra / Mirga Grazinyte-Tyla

Symphony Hall, Birmingham

Saturday 24 November 2018, 11am

Weinberg Symphony no.21 op.152

Shostakovich Symphony no.15 in A major op.141

Written by Richard Whitehouse

The Weinberg Weekend being held in Birmingham reached its culmination tonight with this uncompromising yet rewarding symphonic double-bill. Those unfamiliar with the composer’s music may have been disconcerted by what they heard. Whereas the early Violin Concertino (heard at the previous concert) feels not so far removed from comparable works by Malcolm Arnold, the Symphony no.21 breathes an air of stark fatalism. Written at a time which witnessed the collapse of the Soviet Union and dedicated to the memory of those who died in the Warsaw Ghetto (the ‘Kaddish’ subtitle is found in his catalogue but not the actual score), it ranks among Weinberg’s deepest statements. At almost an hour it is also among his longest symphonies, so making its predominant sparseness and concentration the more remarkable.

The single movement falls into several continuous sections – an initial Largo’ introducing the plangent hymn that pervades the work then the chorale whose presence Weinberg traced back to his First Symphony, their alternation making way for the opening theme of Chopin’s First Ballade intoned somnolently on piano. An Allegro draws a theme from Weinberg’s Fourth Quartet into its reckless orbit, while a further Largo similarly utilizes one from his Double-Bass Sonata – the latter’s sepulchral tones sounding more bizarre given the ensuing klezmer-like passage with clarinet, which persists through a tensile Presto then plaintive Andantino that brings the principal climax. A final Lento unfolds with increasing introspection – violin, piano and harmonium adding their spectral sonorities until the music fades out of earshot.

The work went unheard in Weinberg’s lifetime, with its undoubted technical and emotional challenges having made revivals rare. Yet its formal cohesion and expressive consistency are undoubted – in the conveying of which, Mirga Grazinyte-Tyla took especial credit for rendering the epic structure as an inevitable yet cumulative entity whose febrile outbursts were held in check by that encroaching vastness which extends right across the whole. She was abetted by an assured response from the City of Birmingham Symphony, bolstered by members of Kremerata Baltica (Gidon Kremer taking the violin solos), and if dividing the vocalise between eloquent Maria Makeeva and plaintive Freddie Jemison slightly disrupted continuity in the closing stages, it hardly distracted from the stature of this reading overall.

Shostakovich‘s Symphony no.15 made a pertinent coupling, with Grazinyte-Tyla having its measure right from her purposeful take on the opening Allegretto. The Adagio’s ominous tread was finely sustained, its numerous solo passages having ample room to unfold prior to an anguished climax then desolate coda, while the brief scherzo fairly crackled with barbed irony. Nor was there any lack of focus in the finale, emerging from its miasma of allusions through to a spectral passacaglia whose seismic culmination never pre-empted the subdued recollection of earlier ideas or, above all, the transfigured conclusion with its evocation of ‘voices overheard’ over simmering percussion. It set the seal on an impressive performance and a memorable concert: one which certainly warrants the proposed commercial release.

Sunday morning saw a lecture in the Recital Hall at the recently-opened Royal Birmingham Conservatoire. As presented by Prof David Fanning (Manchester University) and Dr Michelle Assay (Huddersfield University), Exploring Weinberg offered a selective though consistently informative overview of the composer’s life and career: from his formative years in Warsaw, via his arrival in Moscow following periods in Minsk then Tashkent against the background of war; the dark years of the anti-formalism campaign then his incarceration during the final months of Stalin’s increasingly paranoid rule, then to the decades of growing acclaim from colleagues and public alike during the 1960s and ’70s, before a period of increasing neglect as a new generation of Soviet composers came to the fore and the Soviet Union neared its end.

The lecture was illustrated with numerous visual and musical examples, but it was archival recording of Weinberg playing and singing extracts from his opera The Passenger to the Moscow Union of Composers – in a futile attempt to secure its performance – that riveted attention. Hearing a composer’s actual voice is seldom less than revealing and so it proved here, setting the seal on an event which was certainly worth attending despite the absence of a selection of chamber works from Conservatoire students that was to have followed.

Summing up, the Weinberg Weekend fairly succeeded in terms of introducing Birmingham audiences to music by a composer whose importance continues to increase and as a prelude to what looks set to be a deluge of UK performances over the course of his centenary year.

Further information on the Weinberg Weekend can be found here