Here is a nod in the direction of the English Music Festival, returning next month for 2024. For the first time, all festival events will be held in Dorchester-on-Thames. The concerts will take place in Dorchester Abbey, while the talks will be held in the historic Village Hall. The details, copied from the press release, are below:

The seventeenth annual English Music Festival (EMF) returns to Dorchester Abbey, Oxfordshire from Friday 24 May until Bank Holiday Monday 27 May 2024. Celebrating anniversaries of two of Britain’s greatest composers across the event, the opening concert, given by the BBC Concert Orchestra and conductor Martin Yates, features Stanford‘s Clarinet Concerto with soloist Michael Collins, and Holst‘s ‘Cotswold’ Symphony. Vaughan Williams’s ‘Richard II’ Concert Fantasy is given a World Premiere, alongside works by Doreen Carwithen and Frederick Delius. Orchestral, chamber and choral concerts continue throughout the weekend.

The English Music Festival celebrates the brilliance, innovation, beauty and richmusical heritage of Britain with a strong focus on unearthing overlooked or forgottenmasterpieces of the late-nineteenth to mid-twentieth century.

“Each year audience feedback proclaims the latest EMF the best yet and we are delighted to be able to continue developing and improving our now much-loved Festival”, says Em Marshall-Luck, Festival Founder-Director. “This year’s is typical EMF programming, in the range from solo piano recitals to full orchestra and choral concerts, and from early music through to contemporary, while we retain our focus on the EMF’s raison d’etre, those overlooked and forgotten works by British composers of the Golden Renaissance.

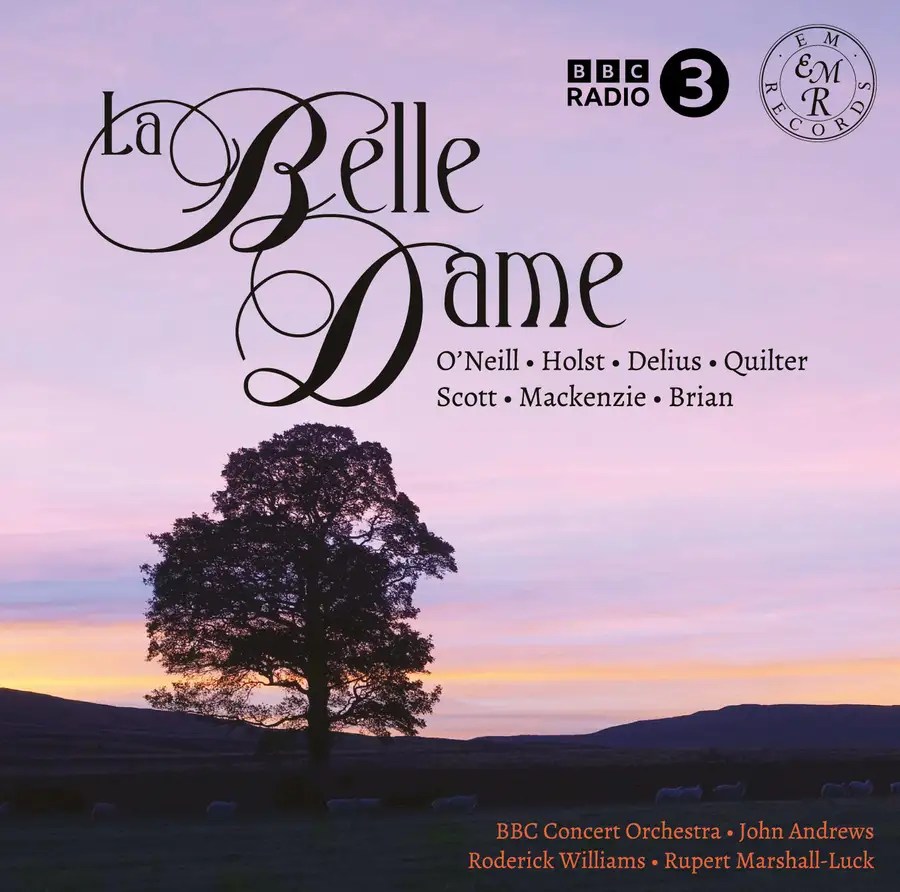

“We are delighted to have been able to attract top performers from abroad, with musicologist, tenor and English-music expert Brian Thorsett joining us from the USA and brilliant pianist Peter Cartwright from South Africa, where the EMF has a collaboration with the University of Witswatersrand in Johannesburg. I am particularly looking forward to their concerts, as well as-in particular-the Vaughan Williams premiere with the BBC Concert Orchestra, and the first modern performance of a gorgeous work by Sir Thomas Armstrong, as well as pianist and Radio 3 presenter, Paul Guinery‘s late-night recital, which celebrates the release of his third disc of Light Piano Music for the Festival’s own record label, EM Records.” The works of Gustav Holst (1874-1934) have been at the heart of Founder-Director Em Marshall-Luck’s programming at the EMF and remain a perennial favourite amongst audiences, with many memorable performances of the composer’s often overlooked major works having been given, as well as recorded by the Festival’s independent recording arm, E M Records. This year, the composer’s early Symphony, ‘The Cotswolds’, takes centre stage.

One of the leading musicians of his generation – as performer, conductor, composer, teacher and writer, Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924) had a profound effect on the development and history of English music. In addition to the Directorship of the Royal College of Music, amongst other august musical establishments, and his influence on several generations of composition students who went on to became household names, Stanford was a prolific composer, completing seven symphonies, eight string quartets, nine operas, more than 300 songs, 30 large scale choral works and a large body of chamber music.

The centenary of his death this year provides an opportunity for evaluation of some works from the large canon that have fallen under the radar. For the EMF’s opening concert, there will be a rare performance of Stanford’s Clarinet Concerto featuring one of today’s leading exponents of the instrument, Michael Collins.

WORLD PREMIERES

First performances include the World Premiere of Ralph Vaughan Williams’s ‘Richard II’ Concert Fantasy; the complete incidental music the composer was commissioned to write for Frank Benson’s 1912-13 production at Stratford, which will be performed by the BBC Concert Orchestra under Conductor, Martin Yates.

Vaughan Williams first discovered Shakespeare as a child when he was given the complete edition by his relative, Caroline Darwin, and ‘Richard II’ become a favourite. The composer took Shakespeare’s many references to English folk-ballads as supporting his own ‘national’ approach to music, saying “Shakespeare makes an international appeal for the very reason that he is so national and English in his outlook.” He went on to set and write over 20 Shakespeare texts and incidental music, often using folk-songs and ballads, and the well-known ‘Greensleeves’ appears in ‘Richard II’.

CHORAL CELEBRATIONS

The EMF regularly showcase live choral music. This year The Godwine Choir and Holst Orchestra conducted by Hilary Davan Wetton bring a programme of popular favourites to Dorchester Abbey, including a first modern performance of Edward Elgar’s ‘Give Unto the Lord’, and Excalibur Voices perform works by Coleridge-Taylor, Milford, Dyson, Bainton, Walford Davies and others.

INTERNATIONAL APPEAL

Returning to the EMF is South African pianist Peter Cartwright, who joins violinist Rupert Marshall-Luck in recital to perform works by Holst, Farrar, Stanford, Bliss and Howells.

American tenor Brian Thorsett and pianist Richard Masters, who enjoy a particular association with British music, are making their first appearance at the EMF with a programme of Finzi, Ireland, Frank Tours and Somervell.

RELAXED LISTENING

John Andrews raises the baton for the English Symphony Orchestra in a programme of works by Finzi, Delius, Howells, Milford, Dyson and Warlock, while Piano Trio, Ensemble Kopernikus, performs Delius, Holst, Rebecca Clarke, John Ireland and Percy Hilder Miles. Pianist and British music specialist, Phillip Leslie, performs works by Rawsthorne, Bowen, Dyson, Leighton, and John Ireland’s masterpiece, ‘Sarnia’.

Rosalind Ventris and Richard Uttley will be performing works for viola and piano including Rebecca Clarke’s Viola Sonata. Rosalind’s album ‘Sola’ is currently nominated for a BBC Music Magazine award in the 2024 ‘Premiere’ category.

Always a popular fixture, late-evening recitals are a special feature of the EMF, with the ancient warmth of Dorchester Abbey providing the perfect setting for audiences to relax in and enjoy a performance from The Flutes & Frets Duo – Beth Stone (historical flutes) and Daniel Murphy (lute; theorbo and guitar), and for a discovery of the lighter side of British composers when pianist Paul Guinery returns to the keyboard. Informative talks include those on anniversary composers, Stanford and Holst, as well as Farrar and Bliss.

This year, the Festival is remaining in Dorchester-on-Thames for the duration of the long weekend.

FURTHER INFORMATION

Further information including the full programme is available on the EMF’s website

Tickets go on sale via the website from 22 March (8 March to Festival Friends) and by means of a postal booking form. Full Festival and Day Passes are also available. Tickets for individual concerts will be available on the door, subject to availability