BBC Singers (What Man Is He?, Festival Anthem), BBC Concert Orchestra / Alice Farnham

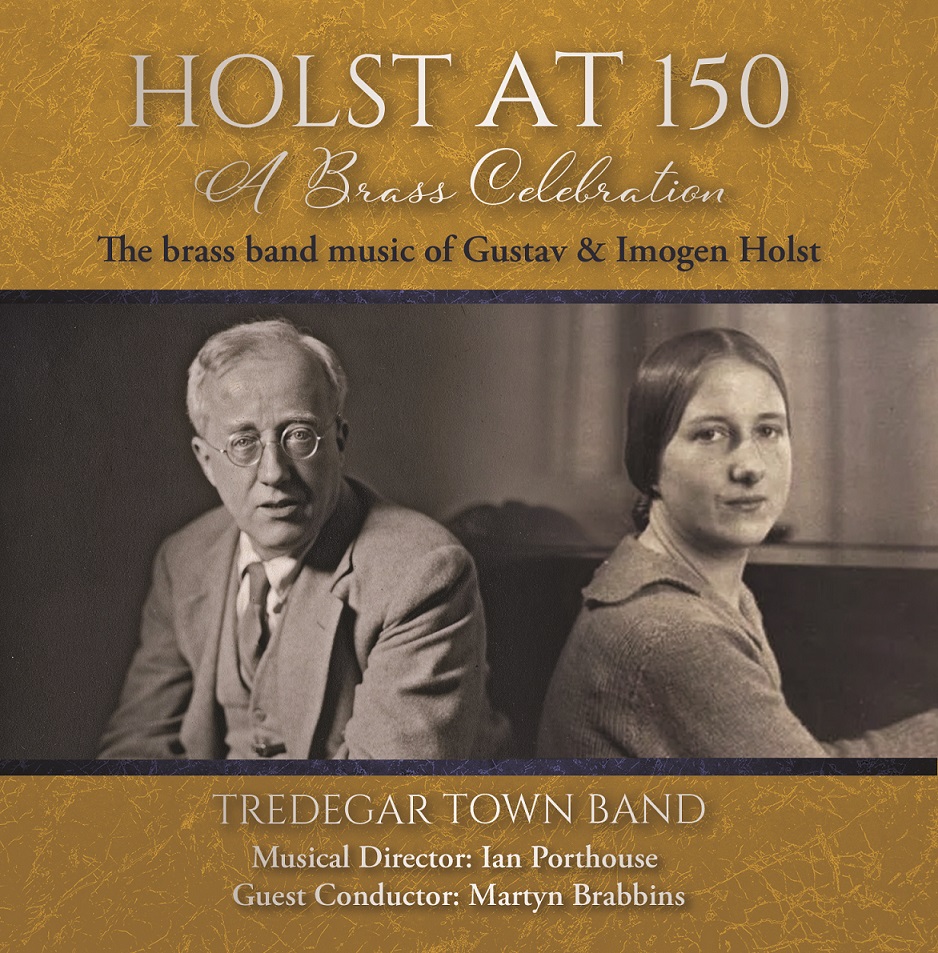

Imogen Holst

Persephone (1929)

Variations on ‘Lorth to Depart’ (1962)

What Man is He? (c1940)

Allegro Assai (1927)

On Westhall Hill (1935)

Suite for String Orchestra (1943)

Festival Anthem (1946)

NMC Recordings NMCD280 [75’01”] English texts included

Producer Colin Matthews Engineers Marvin Ware, Robert Winter, Callum Lawrence

Recorded 27-29 January 2024 at Maida Vale Studio One, London

Reviewed by Richard Whitehouse

What’s the story?

As its executive producer Colin Matthews notes in his introduction, NMC would likely not exist had it not been for Imogen Holst (1907-84) setting up the Holst Foundation prior to her death – so making this release of her larger-scale works the more appropriate, and welcome.

What’s the music like?

The present anthology affords what seems a plausible overview of its composer’s output. The earliest piece here is Allegro Assai, evidently planned as the opening movement of a suite for strings that progressed no further, but which proves characterful and assured on its own terms. Such potential feels well on the way to being realized in Persephone, an overture (albeit more akin to a tone poem) given in rehearsal by Malcolm Sargent, with the influence of Ravel (and indirectly of Vaughan Williams) balanced by the dextrous handling of motifs across a formal evolution such as relates the myth in immediate and individual terms. That this went unheard until the present recording was likely as much a loss to the musical public as to Holst herself.

Underlining its composer’s skill in writing for amateurs, On Westhall Hill is an atmospheric piece the more appealing through its brevity and modesty of scoring. Deriving its text from the Book of Wisdom, What Man Is He? traverses a range of emotions from the sombre, via the introspective, to the affirmative in a setting as searching as it is fervent. Most impressive, however, is the Suite for String Orchestra composed for a ‘portrait’ concert at Wigmore Hall. The four movements unfold from a diaphanous Prelude, via a fluid and astringent Fugue then an Intermezzo whose ruminative warmth hints at qualities rather more fatalistic, to a Jig which convincingly rounds off the whole work with its mounting energy and resolve.

Written in the wake of the Second World War, Festival Anthem went unheard at this time but could be thought a ‘song of thanksgiving’. Adapted from Psalm 104 (‘Praise the Lord, O my soul’), it seamlessly integrates soloistic with choral passages prior to a calmly fulfilled close. The latest work here, Variations on ‘Loth to Depart’ takes a 17th-century tune as harmonized by Giles Farnaby as basis for five variations – the initial four respectively trenchant, eloquent, wistful and incisive; prior to a relatively extended chaconne as distils a pathos the more acute for its understatement. A string quartet is combined resourcefully with double string orchestra in music which can at least hold its own in the context of a distinctive genre in British music.

Does it all work?

It does indeed. It is all too easy to think of Imogen Holst as one who never fully realized her potential in the face of life-long teaching and administrative commitments, but the range of what is heard amply indicates her creative legacy to be one worth exploring in depth. The recordings, moreover, could hardly be bettered in terms of their overall conviction – Alice Farnham securing a laudable response form the BBC Concert Orchestra and, in the choral pieces, BBC Singers. Hopefully other ensembles, professional or amateur, will follow suit.

Is it recommended?

It is indeed. Sound is unexceptionally fine, with informative notes from Christopher Tinker. Alongside the NMC release of her chamber music for strings (D236), and that on Harmonia Mundi of choral music (HMU907576), this is a fine demonstration of Imogen Holst’s legacy.

Listen & Buy

You can listen to samples and explore purchase options on the NMC Recordings website. For more information on the artists, click on the names to visit the websites of the BBC Singers, BBC Concert Orchestra and conductor Alice Farnham, while a dedicated resource can be found for Imogen Holst herself

Published post no.2,374 – Tuesday 26 November 2024

Cellist Steven Isserlis is one of Britain’s best-loved classical artists – loved for his highly respected interpretations of the cello repertoire, but also for his open, honest and enthusiastic approach to classical music.

Cellist Steven Isserlis is one of Britain’s best-loved classical artists – loved for his highly respected interpretations of the cello repertoire, but also for his open, honest and enthusiastic approach to classical music.