Jennifer France (soprano), London Philharmonic Orchestra / Edward Gardner

Abrahamsen let me tell you (2012-3)

Mahler Symphony no.4 in G major (1892, 1899-1900)

Royal Festival Hall, London

Friday 3 October 2025

Reviewed by Richard Whitehouse

Tonight’s London Philharmonic Orchestra concert featured the welcome revival of a 21st-century classic. Hans Abrahamsen’s recent output may be relatively sparing, but the works that have emerged represent a triumph of quality over quantity and not least let me tell you.

Set to fragmentary lines drawn by Paul Griffiths from his eponymous novel, this centres on the character of Ophelia – its seven songs falling into three larger parts whose outlining of a ‘before, now and after’ trajectory gives focus to the arching intensity of its 30-minute span. The first, fourth and sixth of these anticipate what comes to fruition during the second, fifth and seventh – the exception being the third whose speculative vocal line is underpinned by a stealthy progress in the lower registers evoking the motion, if not the form, of a passacaglia. Elsewhere the voice evinces an intricacy and translucency that effortlessly carries the word-setting as it pivots between thought of oblivion and transcendence, before eventually being subsumed into the orchestra for a conclusion among the most affecting in recent memory.

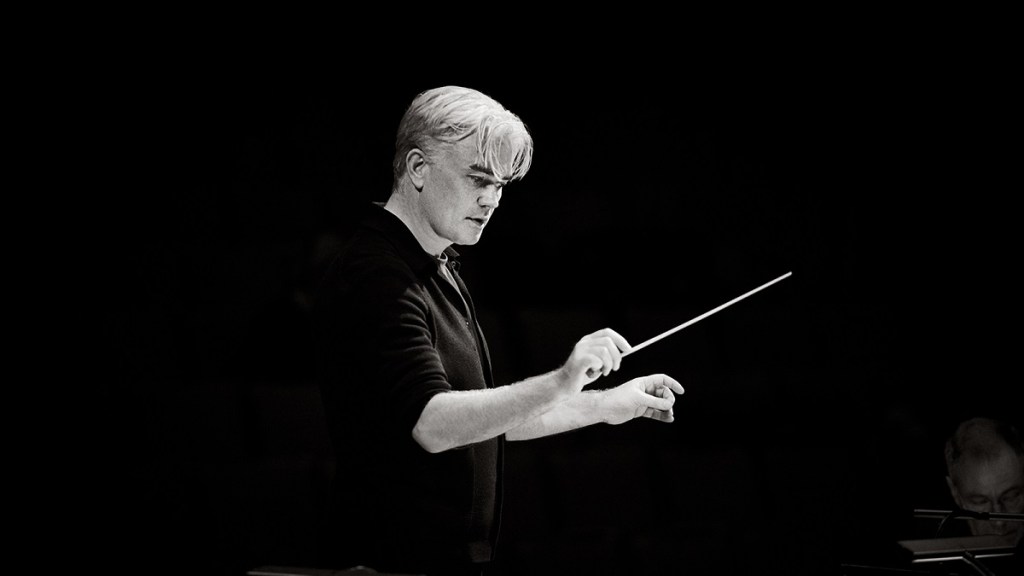

The LPO acquitted itself ably in music which is texturally complex for all its harmonic clarity, though it was Jennifer France (above) who (not unreasonably) most impressed with a rendering of the solo part as did ample justice to its high-lying melisma and airborne flights of fancy. Edward Gardner directed with an innate sense of where this music was headed, not least in those final bars with their tapering off into silence. Relatively few pieces are recognized as seminal from the outset, but let me tell you is one such and seems destined to remain so well into the future.

France then returned (or rather stole in) for the finale of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony after the interval. His setting of ‘Das himmlische Leben’ from the folk-inspired anthology Das Knaben Wunderhorn had actually been written almost a decade earlier and was once envisaged as the finale to the Third Symphony, but it makes a natural conclusion to a successor whose relative understatement is sustained right through to this movement’s intangible end: a ‘child’s vision of heaven’ whose intended innocence becomes informed with no little experience by the close.

Gardner had steered a convincing trajectory through the preceding movements – not least the opening one whose mingled whimsy and wistfulness took on a more ominous demeanour in its eventful development, before conveying unalloyed resolve in a warm-hearted reprise and beatific coda. What is among the most striking of Mahler’s scherzo’s proceeded with audible appreciation of its pivoting between the sardonic and sublime, Pieter Schoeman’s ‘mistuned’ violin being first among equals in music whose soloistic textures were thrown into relief by the homogenous stability of the Adagio. Its double variations unfolded with a fluid intensity capped by a coda whose ‘portal to heaven’ yielded thrilling resplendence as subsided into a transcendent raptness that, in other circumstances, could have made a satisfying conclusion.

That this lead so seamlessly into the vocal finale says a great deal for Mahler’s foresight, but also Gardner’s ability to fashion so cohesive a symphonic entity. As the music subsided into subterranean chords on harp, the audience was (necessarily) held spellbound a while longer.

Click on the links for more information on the London Philharmonic Orchestra, conductor Edward Gardner, soprano Jennifer France and composer Hans Abrahamsen

Published post no.2,679 – Monday 6 October 2025