The cellist talks to The cellist talks to Ben Hogwood about his Wigmore Hall residency, celebrating the music of Fauré, and his new Boccherini album Music of the Angels.

For cellist Steven Isserlis, November 2024 is all about two composers. From the first day of the month he is taking up residence at London’s Wigmore Hall for a five-day exploration of the late chamber music of Gabriel Fauré, who died on 4 November 1924. He has given a valuable insight into his thoughts on the composer in an article just published for the Guardian newspaper, but was generous to spend some time answering specific questions about Fauré’s late music for Arcana.

Arcana: The Wigmore Hall concerts put Fauré (above) in context with his contemporaries

– how did you plan them? It’s especially good to see the music of Nadia

Boulanger, Saint-Saëns and Koechlin included.

Steven: Well, first came the idea of doing the complete (major) chamber music of Fauré for the centenary; then everything else had to be worked out around that. It took some time for the programmes to fall into place – and then I was amazed that the Wigmore said yes to all five of them!

How does Fauré’s writing for the cello develop through his works?

I don’t think of his cello writing as such developing – it’s more the musical content. His first work for cello was the Élégie, which is of course wonderful; but if you compare it to the most similar subsequent piece of his, the slow movement of the second sonata, you see how much more profound his music has become. Which is not to put down the Élégie – any more than saying that Beethoven’s last piano sonata in C minor, op 111, is on a higher level than the Pathétique sonata op 13, also in C minor, is a criticism of the Pathétique.

What are the challenges and ‘do nots’ of performing his music in an ensemble such as a piano quartet or quintet?

We just have to agree on our approach – but we do! I call our team – Joshua Bell, Irène Duval, Blythe Teh Engstroem, myself, Jeremy Denk, Connie Shih – Team Fauré. We’re all in love with his music!

Fauré’s late period has some similarities with that of Brahms. Would you say there is anything in common between their approach, late in life?

I suppose, in that there is a ‘new simplicity’; but I think there’s much more in common between late Fauré and late Beethoven. And not just because both men were profoundly deaf!

There is something very special about Fauré’s melodic writing, and the chromatic harmonies he uses. It must be a joy to play!

It is! So long as one understands the chromatic harmonies – one has to be absolutely sensitive to each change of tonal colour.

Would you say Fauré is a composer where repeated listening brings ever

greater rewards?

Well – yes, of course; but I’d say that of any great composer! But perhaps with Fauré’s late works in particular, familiarity with the style is especially helpful.

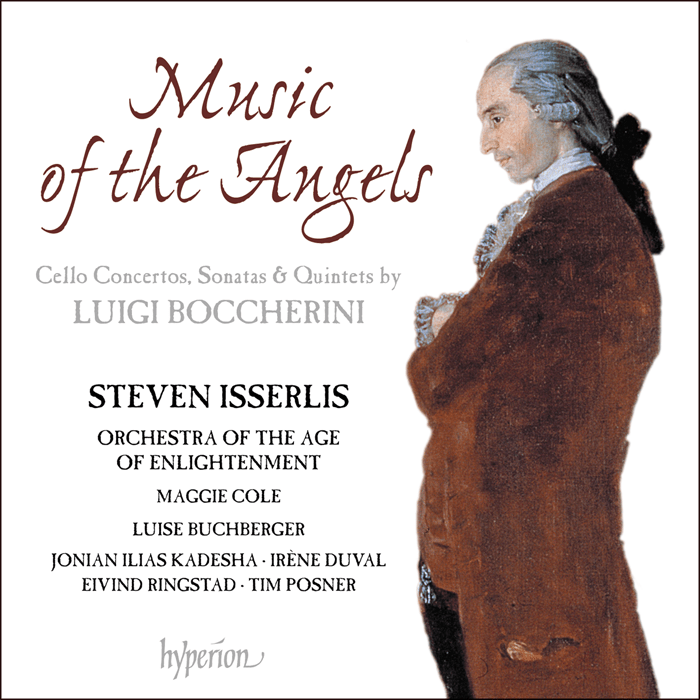

The other composer occupying Steven’s uppermost thoughts in the next month is Luigi Boccherini, with Hyperion releasing Music of the Angels, a generous anthology of the composer’s works for cello with members of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment and harpsichordist Maggie Cole. The album explores the very different forms of Cello Concerto, Cello Sonata and String Quintet – where the composer adds an extra cello to the traditional string quartet line-up. Boccherini is a lesser-known light from the 18th century, and his cause has been close to Steven’s heart right through his recording career.

It’s great to see your Boccherini album. Was it most important for you to present the different types of work – concerto, quintet, sonata – in context?

Thank you! Again, the programme just worked out that way; but yes, I was happy to show different facets of Boccherini’s unique world.

You’ve been playing and recording the music of Boccherini for a good while – what was it that first attracted you to his music?

Well, my teacher Jane Cowan was a great Boccherini fan, which I’m sure influenced me. (She was also a great Fauré fan!) But I’ve always loved his elegance, the otherworldly beauty of his music, his gentle, kind musical soul.

At a guess, I think it might have been the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment’s first exposure to Boccherini. Did they enjoy it as much as you?

I think they MIGHT have done some of the symphonies; but I’m not sure. They were certainly lovely to work with – committed, enthusiastic and supportive.

You talk in your notes about the virtuosity Boccherini requires from his soloist – he must have been quite a player. Is it quite intimidating using such a high register of the cello to start with?

Yes! He’s among the most demanding composers for cello, because there’s nowhere one can hide. One can’t just add mounds of vibrato to mask the intonation, for instance. And one has to be able to shape the delicate curves of the music in a way that is naturally graceful; a challenge indeed.

Would you say his music is an ideal ‘next step’ for lovers of Haydn and Mozart?

I think that he’s very different from either Mozart or Haydn – roughly contemporaneous, yes, but another personality entirely. In a way, I think he’s more analogous to Domenico Scarlatti – not because they’re that similar, but because they were both Italians who spent much of their lives in Spain where, relatively cut off from the centre of European musical life, they created their entirely individual compositional worlds.

How does Boccherini’s cello writing contrast with that of Haydn?

Very different! Both can make the cello sing, true; but Haydn uses virtuosity for purposes of excitement, whereas Boccherini uses it much more subtly – usually for lightness and delicacy, frequently evoking birdsong.

With your Boccherini album set for release, are you inclined to record the Fauré trio, quartets and quintets?

Actually, yes; we were originally set to record straight after the festival; but we decided that that would be just too much. So nowthe plan is to record at least the late chamber works (which is the Fauré most in need of advocacy, I feel) next summer in the US. We hope…”

You can book the last remaining tickets for Steven Isserlis and friends’ Fauré residency at the Wigmore Hall website, and explore purchase options for the new Boccherini album Music of the Angels at the Hyperion website. The Wigmore Hall are streaming the Fauré concerts live from their YouTube site

Published post no.2,344 – Sunday 27 October 2024