by Ben Hogwood

What’s the story?

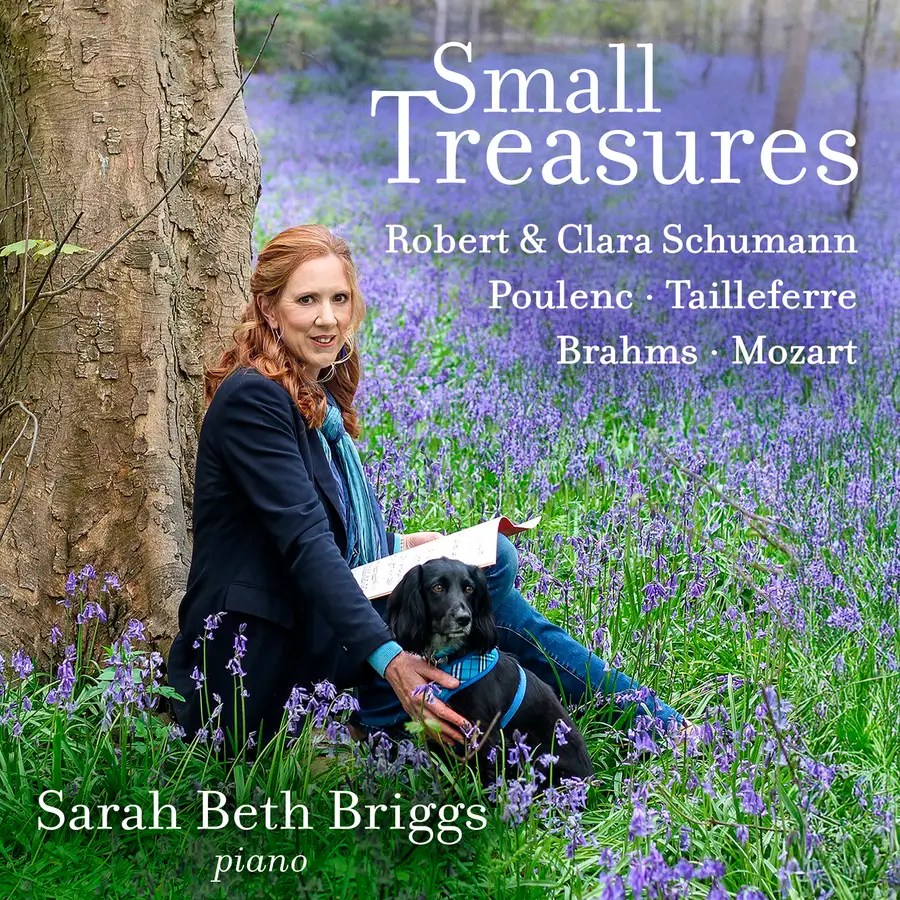

Small Treasures presents a typically inventive programme compiled by pianist Sarah Beth Briggs. In it she presents works by a trio of inseparable Romantic composers, with late-ish Robert Schumann, lesser-heard Clara Schumann and very late Brahms, his final compositions for solo piano.

Complementing these are thoughts from two members of Les Six, Germaine Tailleferre and Francis Poulenc – with the bonus of a cheeky encore from Mozart.

What’s the music like?

In a word, lovely. Briggs is a strong communicator, and finds the personal heart of Schumann’s Waldszenen – which is actually quite a Christmassy set of pieces. She particularly enjoys the intimacy of character pieces like Einsame Blumen (Lonely Flowers) and the delicate but rather haunting Vogel als Prophet (The Prophet Bird), beautifully played here.

A tender account of Robert’s Arabeske is a welcome bonus, an intimate counterpart to the more extrovert Impromptu of Clara. Written in c1844, the piece floats freely on the air in Briggs’s hands. By contrast the Larghetto, first of the Quatre Pièces Fugitives, inhabits a more confidential world, one furthered by a restless ‘un poco agitato’. The Andante espressivo, easily the most substantial of the four, is more serene, and it is tempting to draw a link between this and the mood of Robert’s Traumerei, from Kinderszenen. The Scherzo with which the quartet finishes is charmingly elusive, with clarity the watchword of this interpretation,

Poulenc’s Trois Novelettes are typically mischievous and elegant by turn, spicy harmonies and bittersweet melodies complementing each other, before Tailleferre’s Sicilienne, a charming triple-time excursion with a bittersweet edge.

The Brahms Op.119 pieces are serious but have plenty of air too, and the final majestic Rhapsody is grand but not over-imposing, Briggs resisting the temptation to go for volume over expression.

Does it all work?

It does – and the album is easy to listen to the whole way through, the lightness of the Mozart Eine Kleine Gigue complementing the Brahms at the end. Some of the classic recordings of the Brahms and Schumann pieces arguably find more angst, but these finely played accounts are a treat, especially in context.

Is it recommended?

It is. Rather than visit a playlist on your go-to streaming service, you can just put this album on to create a very satisfying recital. Small Treasures, indeed – as is Sarah’s dog, who joins her on the album artwork!

Listen / Buy

You can listen to Small Treasures on Tidal here, while you can explore purchase options on the Presto website

Published post no.2,756 – Monday 22 December 2025