interview by Ben Hogwood

We still think of Alison Balsom as a new artist, a breath of fresh air for the trumpet in and around classical music. Yet all of a sudden it is nearly 25 years since she burst onto the scene, winning the Brass Final of the BBC’s Young Musician competition in 1998. Since then her recording career has yielded no fewer than 15 albums, for EMI Classics and latterly Warner Classics.

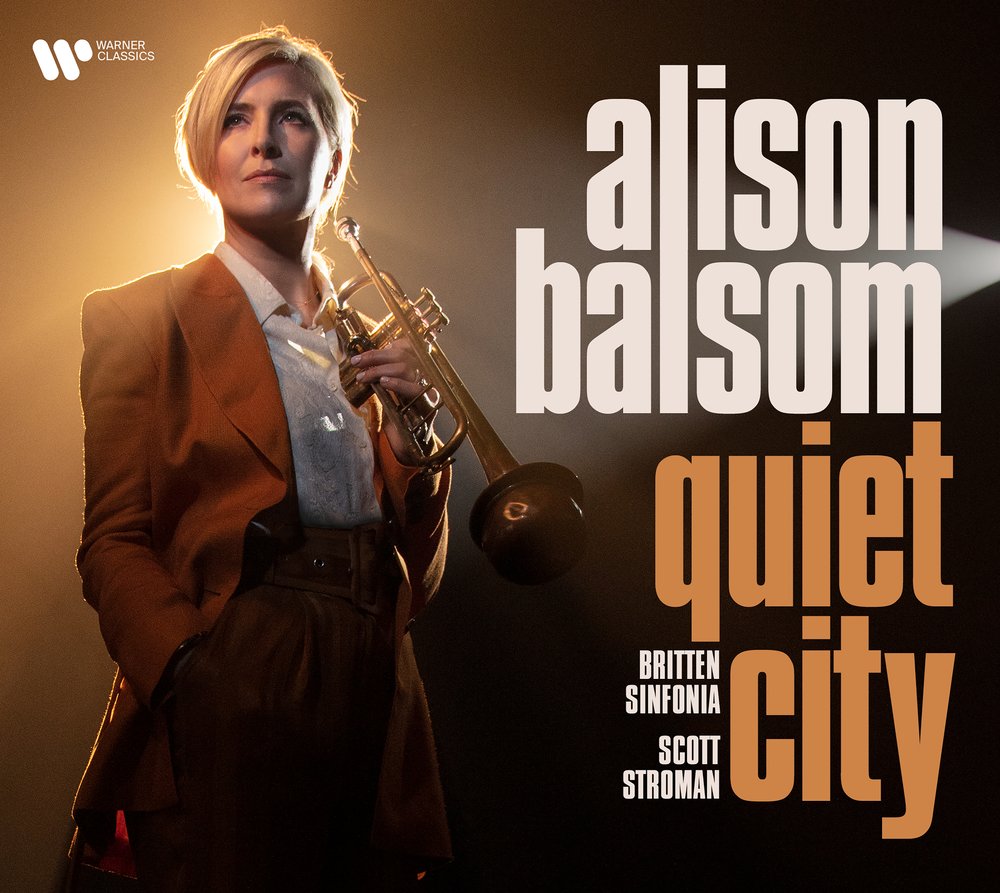

Quiet City will be her 16th – and in many ways it is her most personal album yet, as Arcana found when we sat down for a chat with the trumpeter. Balsom has poured herself a cup of tea, and the chat is punctuated with comfortable silences as she sips tea and I write. An extremely affable presence, she clearly has as much enthusiasm for the music now as she did in 1998, if not more.

Quiet City, as you may have guessed, is named after the Copland composition for trumpet, cor anglais and string orchestra of 1939. A forward-looking piece, it became a popular pick for online concerts during lockdown, its scoring favouring smaller orchestras and its mood wholly redolent of the times. It has held a very significant place in Balsom’s life, too. “I didn’t know I was going to make an album like this”, she confesses. “Quiet City is one of the very first pieces that I fell in love with to a deeper level when playing the trumpet. Copland understands the trumpet’s qualities, the melancholy aspects of the instrument and how it could sing. It is a relatively short work, so it was interesting to think about what it should be programmed with. I don’t think of myself as a jazz trumpeter, yet there is a really interesting point where in America composers were writing ‘in the gap’, letting themselves experiment. It didn’t matter that it was classical or jazz, they were taking from both realms. I found that this made a coherent journey, and found the nuggets growing to album ideas.”

She recognises the relevance of Quiet City to the pandemic. “Copland was a visionary with what we needed. We made this recording in November 2021, when we were just coming out of lockdown. We all had an intense feeling of gratitude to be able to play this music live with a feeling of stillness in the concert hall, a voice that said, “Aren’t we lucky to be here?!” It is such a powerful vision, evoking the atmosphere from the first section, looking between building in New York like an Edward Hopper painting. Even working with a piano reduction I was in a melancholy mood. With this music I think of a film like Lost In Translation, and of two people with a luxury life, going to very different places. There is an isolated melancholy but beauty too, like a friend. As a piece, though, it is technically and physically challenging to play.”

She elaborates further. “Sustaining the notes can be a physical struggle, but you need command of the sound, the articulated notes – and you somehow need to make them tentative and nervous. You want to convey someone practising in an apartment block or something, being wonderfully balanced with the cor anglais and communicating with your audience or listeners.”

The cor anglais part on this recording is taken by Nicholas Daniel, who Balsom professes undying admiration for. “He is such a great musician, and has such a strong feeling about that piece. It was inspiring working with him and getting his insight and thoughts. It was incredible working with the Britten Sinfonia as well, they have great integrity and are always minded for collaboration. I worked with them in 2017, when we did the Barbican’s Sound Unbound festival. We did Miles Davis and Gil Evans’ Sketches Of Spain, using transcriptions from the original studio recordings. I didn’t realise about the manuscripts, and there was a trumpet part revealed to me. He knew exactly what he wanted! I felt privileged to hear the players as at home playing jazz as they do classical.”

Also featured in the Sound Unbound concert was Gershwin’s Rhapsody In Blue, which appears on Balsom’s album in a very different guise – tastefully rejigged to bring the trumpet forward as a second soloist, alongside childhood friend Tom Poster on the piano. “I had a different hat on for this one!” she confesses. “I respect Tom so much, I think he’s the greatest pianist to play with. We met when I was ten, so we know each other really well. With the arrangement I phoned him up and suggested it, and he thought it was nuts but a good idea. We found that Rhapsody in Blue was out of copyright, but not in the Grofé arrangement. This made the job an enormous one for Simon Wright, who orchestrated it from scratch. Any coincidences in the new version are Simon coming to the same conclusion as Grofé, and I think it is an amazing achievement. The piano part didn’t have to be set in stone, which gave Tom the opportunity to express himself even more. We did a concert in Norwich, when everything was closed, and we only had to get it right once to get it in the can.”

She may be 15 albums in, but Alison is keenly aware of how much the format has changed in that time, and how consumption habits are so different with streaming. “The greatest challenge has been finding my muse, making something that the world might want to hear”, she says, “and yet there is an amazing opportunity to pioneer. We put Quiet City with some things that we’re OK with, and some things that are more challenging, such as the Charles Ives piece The Unanswered Question, which I love, but Warner let me go for it. It’s a lucky situation to be in.”

Asking Balsom to cast her thoughts back, I ask who has been an influence on her career to date? “In terms of my teachers, I would say John Miller – an amazing teacher and trumpet guru. With him we focussed on sound, as the trumpet is all about the production of technique. I would compare him to Mr. Miyagi from Karate Kid, he wouldn’t let me do the cool stuff but I’m so glad he did that! I then went on to work with Håkan Hardenberger, who taught me how to teach myself. Physically the trumpet is so challenging, but that’s not how you master it. Getting to Grade 8 is just the start! It has this incredible, multifaceted personality, it reflects who you are. We play our personalities through our instruments!”

Balsom’s husband, film director Sam Mendes, had a small hand in the album’s running order. “He suggested the use of Leonard Bernstein‘s Lonely Town”, she says, and was a good soundboard for how the album was fitting together.” Has she returned the compliment on any of his film scoring? “I have made a few suggestions!” – she smiles – “and of course he has got to know a lot of trumpet repertoire through me.”

She recognises a change of focus in the musical landscape since the pandemic, with much more emphasis on recorded music. In spite of that there are a couple of concerts planned for the rest of the year. “There was the launch concert at Snape, with full bells and whistles, which is quite a complicated affair but the only live version of the album we will be doing. After that it gets quite random, but on October I’ll be doing a recital with Anna Lapwood, the organist, and a lighting designer, at a school in Tonbridge. It’s going to be an immersive trumpet and organ recital. We know the music is amazing but how can we present it and immerse people in the music? I’m really looking forward to doing that, she’s a real force for good! I wanted an amazing acoustic and organ, and there will be a few new pieces for that one.”

Plans are afoot for a seventeenth album, too. “I have had a good chat with Trevor Pinnock about my next project. Over the pandemic we had to re-evaluate travelling and what we have a desire to do – and there are some exciting plans on the horizon!”

You can discover more on Alison Balsom by visiting her website – and you can hear more of Quiet City and purchase the album on the Presto website. Meanwhile for more information on her recital with Anna Lapwood, and to buy tickets, go to the Tonbridge Music Club website