William Byrd

Masses for 4, 3 and 5 voices

The Cardinall’s Musick / Andrew Carwood

Wigmore Hall, London

Tuesday 4 July 2023

Reviewed by Ben Hogwood Photos (c) Benjamin Ealovega

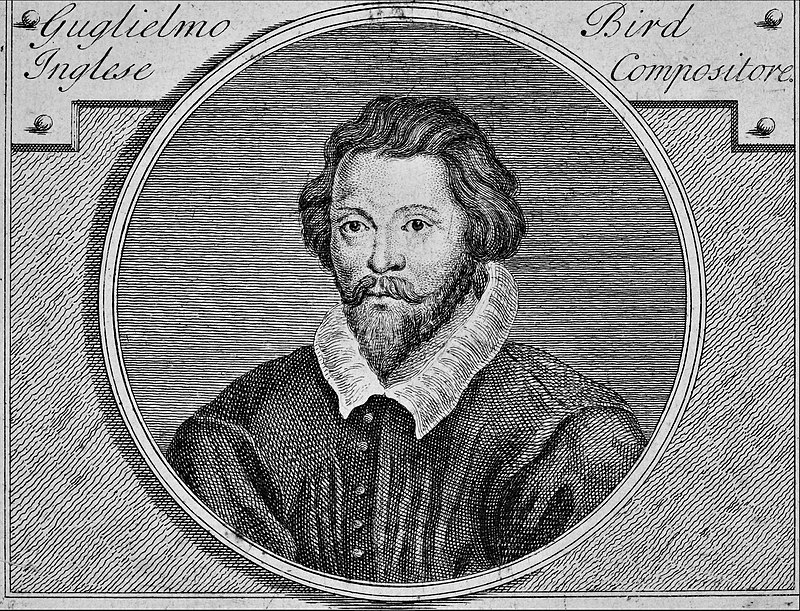

This week we have been marking the 400th anniversary of the death of William Byrd, one of the founding fathers of English classical music as we know it today.

One of the key events on Tuesday, the day itself, was a trio of concerts at the Wigmore Hall from the Cardinall’s Musick choir and their conductor Andrew Carwood. Together they have recorded all of Byrd’s choral music for the Gaudeamus and Hyperion labels, but on this occasion the focus was the composer’s three Mass settings.

Context for these unique works is vital, and it was given by an extremely helpful and thorough note from Katherine Butler, bolstered by musical insight, and also from Carwood himself in well-chosen asides to the audience. Both illustrated vividly how perilous Byrd’s own position as a composer was, for as a Catholic he was compelled to write settings of the mass, despite knowing public airings of the music would be against the demands of his monarch, Elizabeth I, for whom he was royal composer. If discovered, these performances could bring about imprisonment and even death. Because of this, the works lay undiscovered in their largely anonymous packaging, used for very private occasions presided over by a priest who would even have his own bolthole, should the ceremony be discovered.

Byrd

Mass for 4 voices (c1592-3), with the Propers for the Feast of Easter Day

The Cardinall’s Musick [Patrick Craig, Matthew Venner (altos), William Balkwill, Mark Dobell (tenors), Richard Bannan, Robert Rice (baritones), Edward Grint, Nathan Harrison (basses)] / Andrew Carwood

The three Cardinall’s Musick concerts began with a lunchtime account of the Mass for Four Voices, dating from around 1592-3, and given context by in performance by Byrd’s settings of the Propers for Easter, completed in 1607. These began with a celebratory Introit, with its busy acclamation of the resurrection, with the mood changing for a solemn, weighty Kyrie from the Mass. This was given plenty of room by Carwood, with superb control from the singers in their sustaining of the notes. A fulsome Gloria followed, notable for its clarity of line and rhythm. Carwood was judicious in harnessing the ten voices available to him, reducing the forces to five for the Gradual & Alleluia. Here, the portrayal of ‘Mors et vita duello conflixere mirando’ (death and life have fought a huge battle)’ was vividly conveyed, before ‘et gloriam vidi resurgentis’ (‘and I saw the glory of the rising’) reached impressive heights.

The substantial Credo was paced just right, with a holding back from the ‘descendit’, with controlled lower notes to complement. A busy Offertory and graceful Sanctus were beautifully sung, the music gradually unfolding. The Communion (Pascha nostrum) was slow, appropriately reverent and pure, before the moving Agnus Dei had as its end a final chant and response telling us the Mass had finished.

Byrd

Mass for 3 voices (c1593-4), with the Propers for the Feast of Corpus Christi

The Cardinall’s Musick [Julie Cooper, Laura Oldfield (sopranos), Patrick Craig, Matthew Venner (altos), William Balkwill, Mark Dobell (tenors), Nathan Harrison (bass)] / Andrew Carwood

As Andrew Carwood explained, we heard some of the richest music in the first concert, then some of the most intimate in the second. This was music of the recusant house rather than the big church or cathedral, and Carwood invited us to imagine we were in a building no bigger than a sitting room. With Catholics shrouded in secrecy, he gave an idea of just how risky this music making was.

We heard the Mass For Three Voices, with a noticeable reduction in texture from the lunchtime concert, as well as less movement within the parts. That said, there was an air of restrained celebration all the same. A quick Kyrie & more florid Gloria was sung with two to a part, and while the single parts could be left exposed they were very secure in these hands, notably the tricky entries from on high. The Propers on this occasion were for the feast of Corpus Christi and were published in 1605. They featured a ‘risky’ Gradual, before a six-piece Credo found a lovely peak on the words ‘Et ascendit in caelum (and ascended into heaven)’ and a beautiful confluence at the end. There was a suitably thoughtful start to the Sanctus, which became more florid in its ‘Hosanna’ exultations. The Communion was outwardly expressive, retreating to a sombre Agnus Dei and a solemn final chant.

Byrd

Mass for 5 voices (c1594-5), with the Propers for the Feast of All Saints

The Cardinall’s Musick [Julie Cooper, Laura Oldfield (sopranos), Patrick Craig, Matthew Venner (altos), Ben Alden, William Balkwill, Mark Dobell (tenors), Edward Grint, Robert Rice (bass)] / Andrew Carwood

Finally the evening concert gave the Mass for Five voices with the Propers for the Feast of All Saints of 1605 – an effervescent celebration but becoming more meditative as the music proceeded. Carwood, revelling in the occasion, conducted with great sensitivity once again, presiding over a busy Introit with the rejoicing angels. The layered Kyrie of the Mass itself was ideally weighted, making the most of the chromatic possibilities, before a relatively restrained Gloria. The five voices, with increasingly complex writing, were nonetheless easy to follow, their rhythmic lightness suggesting a dance at the end of the Gradual – Carwood referring to the repartee between the voices.

He then referenced the intensity of Byrd’s writing, the declamation in the Credo and its extraordinary harmony, fusing of madrigal techniques into the mass. It was helpful to have these insights on top of the booklet notes, for Carwood setting Byrd apart as a composer even from the likes of Palestrina. The full ten-voice Credo explored deeply felt power and resonance, an incredibly expressive movement, while the purity of the sopranos shone through in the Offertory. A slow Sanctus gradually gathered pace with more complex writing, before the Communion – making explicit reference to the persecution Byrd felt, gave an appropriate stress to the words ‘propter iustitiam (for righteousness’ sake)’ and showed some well-handled dissonances. Finally an Agnus Dei of solemn, minor key angst found peace at last, capped by the closing sentence.

The choir and their conductor received a deservedly rapturous reception, for their beautiful and controlled singing had given Byrd the best possible remembrance, marking the death of this musical martyr in appropriate style. The Cardinall’s Musick and the Wigmore Hall should be applauded for such a well-conceived and executed trio of concerts, which are highly recommended for online viewing!

You can listen to the Cardinall’s Musick recordings of the Byrd Masses, dating from 2000, on the Spotify link below: