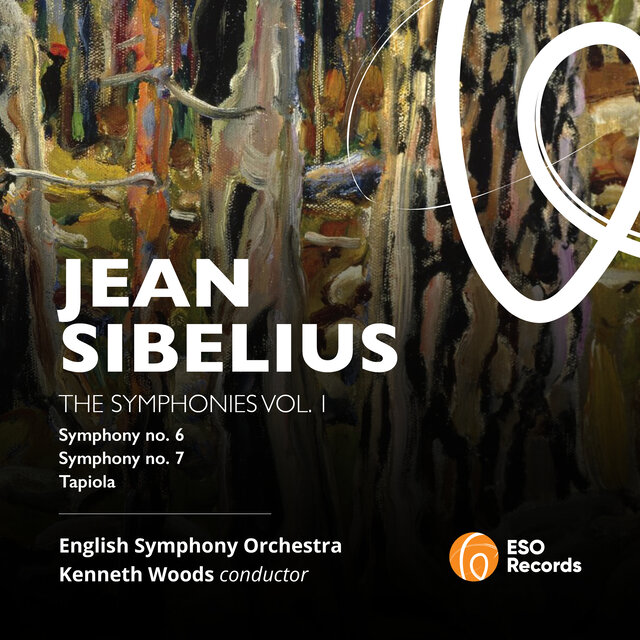

Jean Sibelius

Symphony no.6 in D minor Op. 104 (1918-23)

Symphony no.7 in C major Op. 105 (1923-4)

Tapiola, Op, 112 (1926)

English Symphony Orchestra / Kenneth Woods

ESO Records ESO2502 [67’16”]

Producers Phil Rowlands, Michael Young Engineer Tim Burton

Recorded 1-2 March 2022 (Symphony no.6 & Tapiola); 2 May 2023 (Symphony no.7) at Wyastone Concert Hall, Monmouth

Reviewed by Richard Whitehouse

What’s the story?

Good to find the English Symphony Orchestra issuing the follow-up release on its own label (after Elgar’s First Symphony and In the South), launching an ambitious project to record all seven symphonies and Tapiola by Sibelius prior to the 70th anniversary of his death in 2027.

What are the performances like?

Only if the Sixth Symphony is considered neo-classical does it feel elusive, rather than a deft reformulation of Classical precepts as here. Hence the first movement unfolds as a seamless evolution whose emotional contrasts are incidental – Kenneth Woods ensuring its purposeful course complements the circling repetitions of the following intermezzo, with its speculative variations on those almost casual opening gestures. Ideally paced, the scherzo projects a more incisive tone which the finale then pursues in a refracted sonata design that gains intensity up to its climactic mid-point. Tension drops momentarily here, quickly restored for a disarming reprise of its opening and coda whose evanescence is well conveyed; a reminder that Sibelius Six is as much about the eschewal of beginnings and endings in its seeking a new coherence.

A decisive factor in the Seventh Symphony is how its overall trajectory is sensed – the ending implicit within the beginning, as Sibelius fuses form and content with an inevitability always evident here. After an expectant if not unduly tense introduction, Woods builds the first main section with unforced eloquence to a first statement of the trombone chorale that provides the formal backbone. His transition into the ‘scherzo’ is less abrupt than many, picking up energy as the chorale’s re-emergence generates requisite momentum to sustain a relatively extended ‘intermezzo’. If his approach to the chorale’s last appearance is a little restrained, the latter’s intensity carries over into a searing string threnody that subsides into pensive uncertainty; the music gathering itself for a magisterial crescendo which does not so much end as cease to be.

Tapiola was Sibelius’s last completed major work, and one whose prefatory quatrain implies an elemental aspect rendered here through the almost total absence of transition in this music of incessant evolution. A quality to the fore in a perceptive reading where Woods secures just the right balance between formal unity and expressive diversity across its underlying course. Occasionally there seems a marginal lack of that ‘otherness’ such as endows this music with its uniquely disquieting aura, but steadily accumulating momentum is rarely in doubt on the approach to the seething climax, or a string threnody whose anguish bestows only the most tenuous of benedictions. A reminder, also, that not the least reason Sibelius may have failed to realize an ‘Eighth Symphony’ was because he had already done so with the present work.

Does it all work?

Pretty much throughout. Whether or not the cycle unfolds consistently in reverse order (with a coupling of the Fourth and Fifth Symphonies having already been announced), this opening instalment is the more pertinent for focussing on Sibelius’s last years of sustained creativity.

Is it recommended?

Indeed. The ESO is heard to advantage in the spacious ambience of Wyastone Hall, and there are detailed booklet notes by Guy Rickards. Make no mistake, these are deeply thoughtful and superbly realized performances which launch the ESO’s Sibelius cycle in impressive fashion.

Listen / Buy

You can read more about this release and explore purchase options at the Ulysees Arts website. Click on the names to read more about the English Symphony Orchestra and conductor Kenneth Woods, and for the Ernest Bloch Society

Published post no.2,622 – Sunday 10 August 2025