Saariaho Mirage (2007) [Proms premiere]

Mozart Piano Concerto no.9 in E flat major K271 ‘Jeunehomme’ (1777)

Richard Strauss Eine Alpensinfonie Op.64 (1911-15)

Silja Aalto (soprano), Anssi Karttunen (cello), Seong-Jin Cho (piano), BBC Symphony Orchestra / Sakari Oramo

Royal Albert Hall, London

Friday 9 August 2024, 6pm

reviewed by Richard Whitehouse Photos (c) Mark Allan

Soon to begin his 12th season as chief conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra, Sakari Oramo made his second Proms appearance this season for what proved a typically diverse and resourceful programme whose stretching over 230 years of Western music was the least of its fascinations.

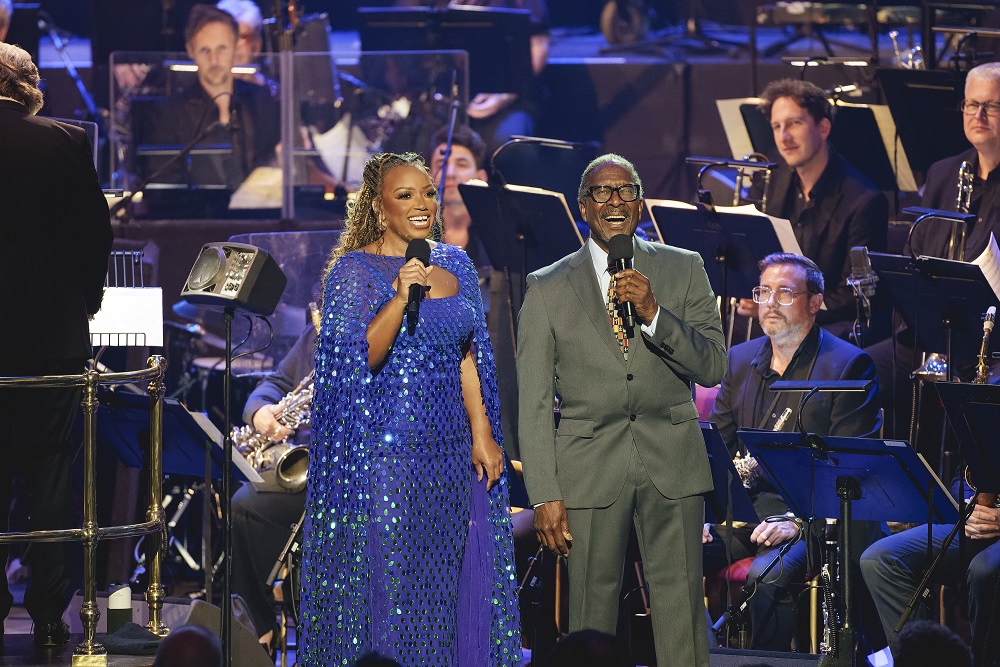

Her untimely death last year made a memorial to Kaija Saariaho more necessary and Mirage was a judicious choice, its setting lines by Mexican shaman María Sabina drawing a suitably theatrical response from Silja Aalto (above) – alongside who, Anssi Karttunen (long-time collaborator with this composer) weaved between the vocal and orchestral writing almost as an ‘alter-ego’ of subdued if beneficent presence. Musically the piece is typical of Saariaho from this period in aligning intricate texture with a mounting fervour at times ecstatic and ultimately fulfilled.

It may have been a ‘jeunefemme’ for whom Mozart actually wrote his Ninth Piano Concerto, but this remains its composer’s earliest unequivocal masterpiece and one with which Seong-Jin Cho (below) evidently feels real affinity. Not least in an opening Allegro whose arresting repartee at the start set the tone for an incisive traversal whose pianistic agility, not least in the first of Mozart’s cadenzas, was never without its inward asides. Such introspection came to the fore in the Andantino, its interplay of archaic and ‘modern’ harmonies yielding a plangency which found soloist and conductor as one. Nor was the finale’s central Menuetto without ruminative poise, set in relief by the buoyant Presto sections either side. Impressive music-making, then, that Cho continued with his deftly eloquent take on the second movement of Ravel’s Sonatine.

The last and most inclusive of Richard Strauss’s tone poems, An Alpine Symphony has received more than its share of tendentious reviews (and perfunctory programme notes), so credit to Oramo for emphasizing those purely musical qualities which, much more than its being a ‘bourgeois travelogue’ or even existential statement, duly determine this most formally and expressively integrated of its composer’s such works. As was evident at the outset: Alpine vistas emerged via a preludial crescendo that headed seamlessly into the ascent with its assembly of offstage horns, placed to advantage on the right of the gallery, then frequently arduous traversal above the treeline and on to the glacier prior to the summit. Its attendant ‘Vision’ drew an affecting soliloquy from oboist Tom Blomfield, then resplendent response from a 125-strong BBCSO.

What goes up tending to come down makes the following portion most difficult to sustain in terms of its ongoing momentum. The present account marginally lost focus here, but not in a mesmeric evocation of that eerie calm before the thunderstorm; organ and percussion adding to the overall mayhem before the relative calm of encroaching sunset. Ausklang is no mere epilogue – here, it afforded transcendence in the amalgam between those human and natural domains, while ensuring an overall fulfilment in the face of night with its inevitable closure.

The piece has come into its own since first appearing at these concerts 42 years ago and, if tonight’s reading did not quite touch all relevant bases, it conveyed the work’s measure like few others in tribute to the continuing creative partnership of this conductor and orchestra.

For more on this year’s festival, visit the BBC Proms website – and to read more on the artists involved, click on the names: Seong-Jin Cho, Silja Aalto, Anssi Karttunen, the BBC Symphony Orchestra and their chief conductor Sakari Oramo, and the official website of Kaija Saariaho and her works

Published post no.2,268 – Monday 9 August 2024