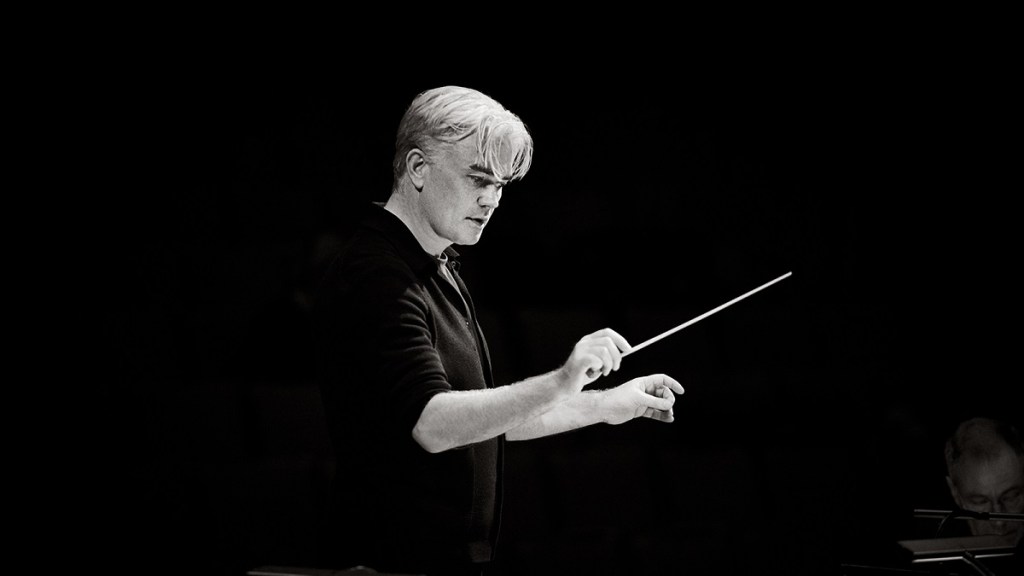

Peter Moore (trombone), City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra / Kazuki Yamada (above)

Mahler Blumine (1884)

Fujikura Trombone Concerto ‘Vast Ocean II’ (2005/23) [UK Premiere]

Mahler Symphony no.1 in D major (1887-88, rev. 1889-98)

Symphony Hall, Birmingham

Thursday 15 January 2026

Reviewed by Richard Whitehouse Photo (c) Andrew Fox

Mahler has not been absent from the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra’s schedule since those halcyon years of Simon Rattle, though even he never undertook a chronological traversal of such as the orchestra’s current music director Kazuki Yamada duly commenced this evening.

Although the First Symphony was heard in its customary four-movement version as finalized for a Vienna performance in 1898, the so-called Blumine taken over from earlier incidental music and included as second movement in the earliest performances was given as an entrée to this concert. With its lilting trumpet melody – effortlessly unfolded by Holly Clark – and its aura of rapt inwardness, this elegant intermezzo was audibly out of place given the transition from symphonic poem to symphony, but it retains an appeal that was winningly evident here.

Two years ago Yamada and the CBSO gave the premiere of Wavering World by Japanese-born composer Dai Fujikura, and it was heartening to see the association continued with this first hearing in the UK for Vast Ocean II. Not so much a reworking as the reconceiving of a piece from 18 years earlier, this trombone concerto unfolded within the context of an orchestra rich in alluring sonorities yet streamlined in texture. This latter entered gradually while remaining focussed on (if never beholden to) a soloist whose role is almost that of a ‘cantus firmus’ that guides the music, through waves of increasing activity, towards a fervent culmination before a suspenseful closing evanescence. It helped to have in Peter Moore a soloist who manifestly believed in the music and contributed greatly to the impact of this memorable performance.

And so to Mahler’s First Symphony that, following on from Yamada’s accounts of the Fourth and Ninth in recent seasons, drew a suitably visceral response from conductor and orchestra. Not that this traversal was without failings: the ‘coming of spring’ in the opening pages was unerringly judged, as too the transition into its genial main theme, though this first movement rather lost focus in the mounting intensity of its final stages which felt rather rushed through. There were no provisos about a scherzo whose impetuous outer sections found ideal contrast with its ländler-informed trio of winning poise. The ensuing funeral march was equally well judged, bassist Anthony Alcock setting in motion this unlikely processional whose pathos is tinged by irony and even ambivalence before its jaunty climax then withdrawal into silence.

Launched with piercing clamour, the finale may ultimately have been no more than the sum of its parts, but the best were indeed memorable. So if the expressive second theme sounded overly generic, the approach to the central peroration was astutely handled, with the hushed recollection of earlier ideas never less than spellbinding. Nor was the stealthy build-up to the apotheosis lacking purpose, even if this latter emerged as less than majestic given Yamada’s headlong rush to those brusque closing chords. Audience response was accordingly effusive.

One person who would no doubt have wanted to be present was Andrew Clements, who died just four days earlier. A regular CBSO reviewer for the Guardian, his laconic while considered observations were always centred on the premise that music, whether in or of itself, mattered.

To read more about the CBSO’s 2025/26 season, visit the CBSO website. Click on the names for more on trombonist Peter Moore, CBSO chief conductor Kazuki Yamada and composer Dai Fujikura

Published post no.2,770 – Saturday 17 January 2026