by Richard Whitehouse

What’s the story?

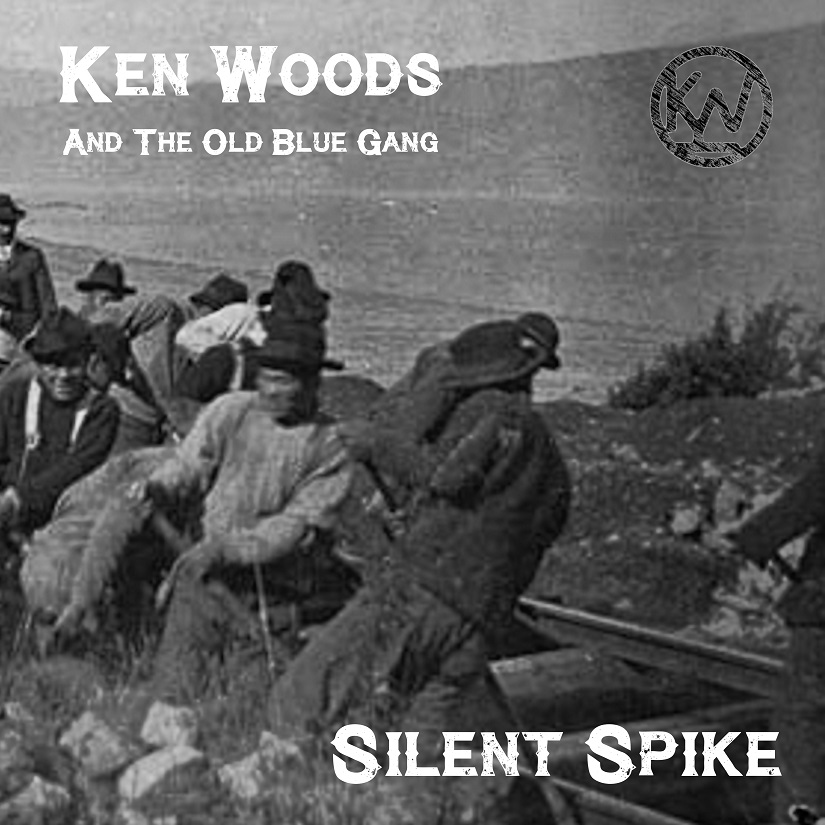

Kenneth Woods issues the debut of his band The Old Blue Gang, less a concept album per se than themed reflections on a shameful while all too typical incident (then as now) of migrant workers who were first exploited then betrayed in the American West of some 150 years ago.

What’s the music like?

Best known as a conductor, notably at the helm of the English Symphony Orchestra for over a decade, Kenneth Woods also works extensively as cellist and guitarist. This latter career is showcased in Silent Spike, the first album with his band The Old Blue Gang, which affords a probing take on the largely forgotten role of Chinese immigrants involved in constructing the Transcontinental Railway line from California via Oregon to Washington. A tale of alienation, exploitation and ostracization which has lost none of its horrific impact over ensuing decades.

Opening track The Voyage emerges ‘Déjà Vu’-like into focus, its commentary about those coming to the New World with little or no expectation delivered in suitably deadpan fashion by Woods, whose searing guitar affords contrast with Joe Hoskin’s methodical yet ominous bass and Steve Roberts’s forceful yet flexible drumming. The arduous workload endured by the immigrants is vividly conveyed by the grunge-inflected Steel Stretcher, before Dead Line Creek puts musicians (and listeners) through their collective paces with its unsparing depiction of mass murder by the gang fronted by Old Blue – an outlaw whose reward is as much destructive as monetary. Much the longest track at 21 minutes and its evolution more instrumentally than narratively driven, this is alt-Americana at its most uncompromising.

It might have been preferable to sequence this epic after the next three tracks, each of them streamed as singles in advance of the album. Sundown Town evokes its intolerance with a fatalism redolent of Johnny Cash, intensified by Lilly White with its chilling recollection of miners being deliberately incarcerated so they need not be paid. Ride the Rails provides a natural continuation with its tale of the immigrants being driven out of town by the under-employed during economic depression, who were (inevitably) acquitted of any wrongdoing. It remains for closing track Gather the Ghosts and Bones to inject a degree of empathy as it recounts the returning of remains of those who received burial in their native China – people otherwise known only through the handful of faded photographs that have come down to us.

Does it all work?

Indeed. Ensemble is unusually dense and layered for a three-piece outfit, though this does not mean excessive ‘noodling’ or wanton virtuosity; the playing being characterized by a restraint or even austerity such as fittingly underlines the grimness of the narrative and the austerity of its realization. Pertinent comparison, conceptually if not musically, can be made with Fairport Convention’s 1971 masterpiece ‘Babbacombe’ Lee – for all that this album touches, however obliquely, upon a redemptive quality understandably absent from what is encapsulated here.

Is it recommended?

Very much so. It hardly makes for comfortable listening, but Silent Spike is a plangent while resourceful treatment of a subject whose contemporary relevance cannot be gainsaid. It also offers intriguing pointers as to where The Old Blue Gang might be headed on future albums.

Listen / Buy

You can explore purchase options on the Kenneth Woods website

Published post no.2,662 – Friday 19 September 2025