Petroc Trelawny (orator), The London Chorus, New London Orchestra / Adrian Brown

Vaughan Williams Six Choral Songs (1940)

Martinů Memorial to Lidice (1943)

Walton Spitfire Prelude and Fugue (1942)

Bliss Morning Heroes (1929-30)

Holst/Rice I Vow to Thee My Country (1921)

Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Square, London

Thursday 9 May 2025

Reviewed by Richard Whitehouse

The London Chorus and New London Orchestra have put on notable concerts in recent years, few more ambitious than this programme to mark not merely the 80th anniversary of Victory in Europe Day but also the 50th anniversary of Sir Arthur Bliss’s death in appropriate manner.

The first half comprised an unlikely but effective sequence of pieces written at the start of or during the Second World War. Rarely revived as such, Vaughan Williams’s Six Choral Songs to be Sung in Time of War works well as a whole: settings of Shelley that touch on aspects of courage, liberty, healing, victory, then pity, peace and war – before A Song to the New Age characterizes its utopian leanings in subdued and even ambivalent terms which seem typical of its composer. Suffice to add that the London Chorus had the full measure of its aspiration.

Two succinct if otherwise entirely different pieces brought out the best from the New London Orchestra. Rarely so overt in emotion, Martinů was well-nigh explicit when commemorating Nazi atrocities in music of plangent harmonies and chorale-like fervency both evocative and affecting. Derived from his score to the film The First of the Few, Walton had come up with a showpiece whose ceremonial prelude is vividly countered by its incisive fugue – making way for a brief if poignant interlude before matters are brought to a head in the rousing peroration.

Although intimately bound up with the First World War, Morning Heroes is wholly apposite for the present context. Conceived as the exorcism of his wartime experiences, Bliss’s choral symphony elides deftly between a distant past and its present; the first of its five movements featuring an orchestral introduction to set out the underlying mood and salient motifs, before Hector’s Farewell to Adromache had Petroc Trelawny eloquently evoking that scene on the ramparts of Troy without excess rhetoric. Adrian Brown’s understated direction meaningfully pointed up the expressive contrast between this and The City Arming – the setting of Walt Whitman whose interaction of chorus and orchestra was powerfully sustained right through to the simmering unease at its close, with the onset of hostilities in the American Civil War.

The two parts of the central movement saw each section of the London Chorus come into its own: the women in Vigil, a confiding take on lines by Li-Tai-Po (Li Bai) such as relates the emotions of those left behind; and the men in The Bivouac’s Flame, plangently evoking life at the front with further lines from Whitman’s Drum Taps. Choral forces reunite in Achilles Goes Forth to Battle, a setting from later in The Iliad which brings about the work’s climax via The Heroes – a rollcall commemorating those of Antiquity. After this, the starkness of Wilfred Owen’s Spring Offensive is the greater for its sparse accompaniment – Trelawny’s oration a model of understatement as this segued into the setting of Robert Nichols’s Dawn on the Somme with those ‘morning heroes’ themselves evoked affirmatively if fatalistically.

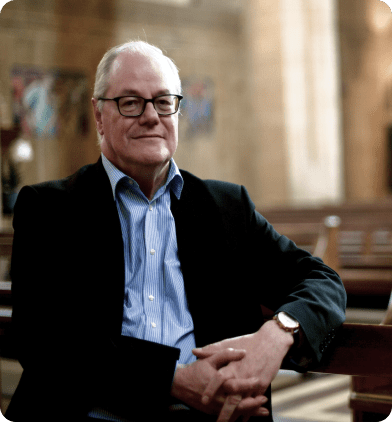

A concert which ended in fine style with Holst’s stirring anthem had begun in subdued fashion with Dawn on the Somme – Ronald Corp’s elegy, given hours after his death was announced. Someone who had always given his all to this chorus and orchestra, he will be greatly missed.

Ronald Corp OBE (1951-2025)

Published post no.2,530 – Sunday 11 May 2025