Recital Hall, Royal Birmingham Conservatoire, Birmingham

Monday 17 & Tuesday 18 February 2025

Reviewed by Richard Whitehouse

Royal Birmingham Conservatoire has put on some notable extended events over recent years, the latest being Best of British – a two-day retrospective of piano music from UK composers past and present, all performed by current, former and associated musicians of this institution.

Monday lunchtime centred on composers ‘Made in Birmingham’, beginning with the Second Sonata of John Joubert. His three such works encompass almost his whole maturity, of which this is the longest – taking in a cumulatively intensifying Allegro, volatile Presto with a more equable trio, then a finale whose fantasia-like unfolding culminates in a powerful resolution. Rebecca Watson was a sure and perceptive exponent. Dorothy Howell’s Toccata was given with verve by Rufus Westley, with Christopher Edmonds’ Prelude and Fugue in G elegantly rendered by Ning-xi Wu. Chiara Thomson was dextrousness itself in Howell’s Humoresque, then Zixin Wen found quixotic humour in her Spindrift, before John Lee and Ruimei Huang enjoyed putting Joubert’s early and engaging Divertimento for piano duet through its paces.

Monday afternoon opened with Frank Bridge – his Three Lyrics given by John Lee with due appreciation of their keen insouciance, as too the menacing aura of his much later Gargoyles. Established as the pre-eminent English art-song composer of his generation, Ian Venables is no less adept in combining violin and piano – witness the expressive poise but also rhythmic impetus of his Three Pieces, to which RBC alumni Chu-Yu Yang and Eric McElroy were as emotionally attuned as they were in plumbing the expressive depths of Gerald Finzi’s Elegy.

Next came John Ireland – his imposing if somewhat discursive Ballade finding a committed advocate in Roman Kosyakov, who had no less the measure of his atmospheric Month’s Mind with its undertones of Medtner. Yinan Tong proved suitably alluring in The Island Spell (the first of Ireland’s Decorations), while Ruimei Hang conveyed elegance as well as playfulness in Bridge’s Three Sketches. Expertly partnered by Sarah Potjewijd, clarinettist Jamie Salters steered an insightful course through the diverting formal intricacy of Ireland’s Fantasy Sonata.

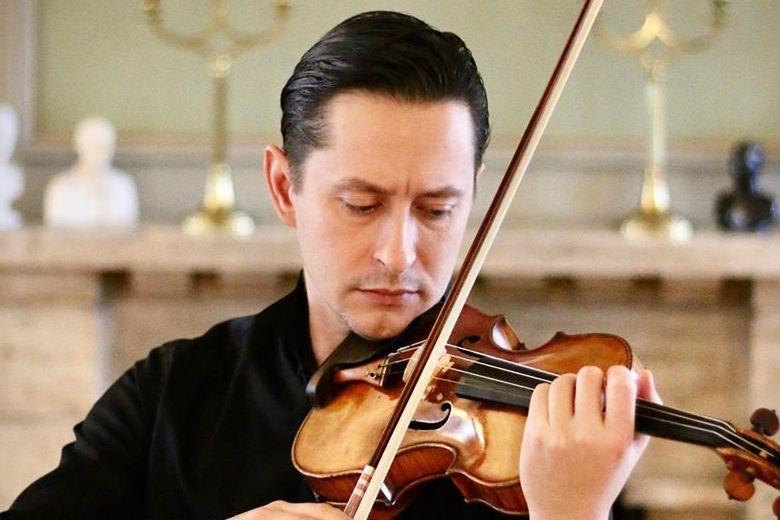

Monday evening commenced with further Ireland in ‘Phantasie’ mode – his First Piano Trio finding a productive accord between its Brahmsian inheritance and his own, subtly emerging personality at the hands of violinist Roberto Ruisi, cellist Nicholas Trygstad and pianist Mark Bebbington. They were joined by violinist Shuwei Zuo and violist Jin-he Huang in Venables’ Piano Quintet, among the most substantial and certainly the best known of his chamber works. Its opening Allegro is preceded by an Adagio whose acute pathos underlies the robust energy of what follows, before a Largo such as takes in the capriciousness of its scherzo-like central section without disrupting its soulful discourse; while the finale’s animation is not necessarily resolved by its slow postlude, a sense of this music come affectingly full circle is undeniable.

The second half found these artists in a performance of Sir Edward Elgar’s Piano Quintet doing full justice to a work which, whatever its eccentricity of form and content, is worthy to stand beside any of his mature masterpieces. How persuasively they elided between the haunting ambivalence of the first movement’s introduction and its trenchant Allegro, with the central Adagio gradually emerging as a statement of great emotional import, then the final Allegro building inevitably to an ending of fervent affirmation. Memorable music-making indeed.

Tuesday lunchtime brought more ‘Made in Birmingham’. Michael Jones gave an interesting overview of his teacher Christopher Edmonds, two more of whose Preludes and Fugues – the elegance of that in E then the rapture of that in A – preceded his Aria Variata which, inspired by wartime experiences in the Crimea, channels the influences of Scriabin and Cyril Scott to personal ends. Zoe Tan teased out unity from within the diversity of Howell’s appealing Five Studies, before Duncan Honeybourne gave of his best in the Third Sonata written for him by Joubert. Inspired by lines from Thomas Hardy on the innate futility of the human condition, its three movements unfold an inevitable trajectory from aggression, through compassion, to a resolution more powerful for its inherent fatalism. A fine piece and performance to match.

Tuesday afternoon brought a varied programme in terms of style and media. Chian-Chian Hsu was alive to the limpid poise of Frederick Delius’s Cello Sonata, while otherwise leaving her attentive pianist Charles Matthews to set the interpretive parameters. Honeybourne was then joined by Katharine Lam in the Sonata for Two Pianos by Andrew Downes – whose subtitle A Refuge in times of trouble indicates the ominous unease, shot through with a consoling warmth, that pervades these three, lucidly designed movements by its underrated composer.

Jing Sun gave her own, attractive take on Bridge’s Rosemary (second of his Three Sketches) – before which, Ren-tong Zhao and Jake Penlington offered an unexpected highlight in Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis as stylishly arranged for two pianos by Maurice Jacobson. A not inconsiderable composer, the latter was represented by his quirky Mosaic with Zijun Pan and Julian Jacobson as fluent duettists; Julian returning for his Piccola musica notturna that feels more Busoni than Dallapiccola, if a haunting study in its own right.

Tuesday evening consisted of four notable works. Daniel Lebhardt opened proceedings with Joubert’s First Sonata, this tensile single movement fusing a variety of ideas into an eventful and, above all, cohesive whole through a masterly formal and motivic development. Not that Ethel Smyth’s Second Sonata was lacking such cohesion and if its three movements, arrayed in the expected fast-slow-fast sequence, seemed indebted to the pianistic idiom of Schumann more than that of Brahms, the unbridled rhythmic elan of its opening Allegro (set in motion by a no less forceful introduction), the gently enfolding harmonies of its central Andante (a ‘song without words’ in spirit), then its impulsive final Presto as surges to an aptly decisive close needed no apology. Just the sort of piece that is worth revival at a festival such as this.

As equally was Howell’s Piano Sonata, its more understated and equivocal emotion no doubt representative of a very different persona and one which Rebecca Watson duly brought out – whether the eddying motion of its initial Moderato, intimate calm of its central Tranquillo, or mounting resolve of its final Allegro to a (more or less) decisive close. Yun-Jou Lin rounded things off with Sarnia – An Island Sequence that is arguably Ireland’s most successful such piece for its keenly evocative quality, as was conveyed here though her scintillating pianism. Quite an embarrassment of riches, but one which came together effectively in performance – thanks not least to Mark Bebbington in his curating of the event. It hardly needs adding that there is an abundance of this music for a ‘Best of British, Part Two’ on some future occasion.

For artist and repertoire details in listing form, head to the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire website – clicking here for Day One and here for Day Two

Published post no.2,455 – Monday 24 February 2025