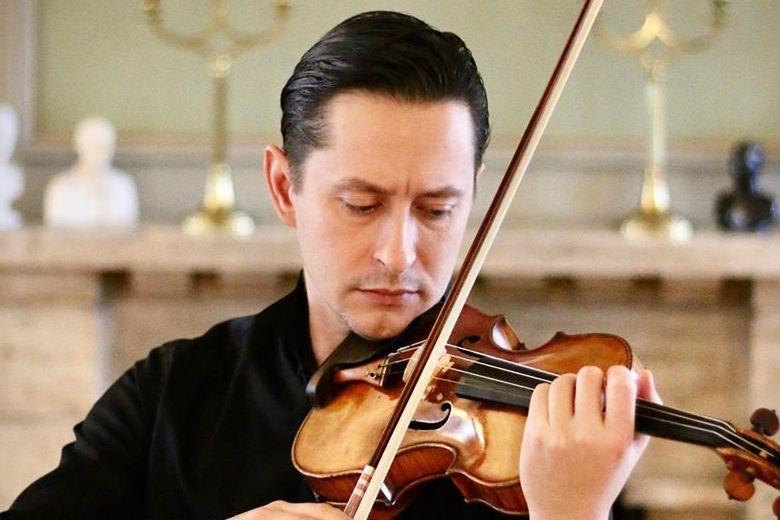

Hyeyoon Park (violin, above), City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra / Alexander Shelley (below)

Gershwin An American in Paris (1928)

Price Violin Concerto no.2 in D minor (1952)

Price arr. Farrington Adoration (1951)

Ravel Le Tombeau de Couperin (1914-17, orch. 1919)

Stravinsky The Firebird – suite (1910, arr. 1919)

Symphony Hall, Birmingham

Thursday 20 February 2025 (2:15pm)

Reviewed by Richard Whitehouse

Although he holds major posts in Canada and Naples and has a longstanding association with the Royal Philharmonic, Alexander Shelley seems not previously to have conducted the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, and this afternoon’s concert made one hope he will return soon.

An American in Paris was a tricky piece with which to open proceedings, but here succeeded well on its own terms. Somewhere between tone poem and symphonic rhapsody, Gershwin’s evocation of a compatriot (maybe himself?) not a little lost in the French capital was treated to a bracingly impulsive and most often perceptive reading. A slightly start-stop feel in those earlier stages ceased well before Jason Lewis’s eloquent though not unduly inflected take on its indelible trumpet melody, with the closing stages afforded a tangible sense of resolution.

Much interest has centred over this past decade on the music of Florence Price – the Chicago-based composer and pianist, much of whose output was thought lost prior to the rediscovery of a substantial cache of manuscripts in 2009. One of which was her Second Violin Concerto, among her last works and whose 15-minute single movement evinces a focus and continuity often lacking in her earlier symphonic pieces (not least a Piano Concerto which Birmingham heard a couple of seasons ago). Its rich-textured orchestration (but why four percussionists?) is an ideal backdrop for the soloist to elaborate its series of episodes commanding, ruminative then impetuous, and Hyeyoon Park made the most of her time in the spotlight for an account that presented this always enjoyable while ultimately unmemorable work to best advantage.

The concerto being short measure, Park continued with an ideal encore. Written for solo organ, Price’s Adoration was given in Iain Farrington’s arrangement that brought out its elegance and warmth, if also an unlikely resemblance to Albert Fitz’s ballad The Honeysuckle and the Bee.

After the interval, music by composers from whom Gershwin had sought composition lessons when in Paris. Orchestral forces duly scaled down, Ravel’s Le Tombeau de Couperin was at its best in a deftly propelled Forlane, the alternation of verses with refrains never outstaying its welcome, then a Menuet whose winsome poise – and delectable oboe playing from Hyun Jung Song – emphasized the ominous tone of its central section. The Prélude was a little too skittish, while a capering Rigaudon was spoiled by an excessive ritenuto on its final phrase.

Interesting how the 1919 suite from Stravinsky’s The Firebird has regained a popularity it long enjoyed before renditions of the complete ballet became the norm. Drawing palpable mystery from its ‘Introduction’, Shelley (above) secured a dextrous response in Dance of the Firebird then an alluring response from the woodwind in Khovorod of the Princesses. Contrast again with the Infernal Dance of King Kashchei, even if its later stages lacked a measure of adrenalin, then the Berceuse had a soulful contribution by Nikolaj Henriques and fastidiously shaded strings. Hardly less involving was the crescendo into the Finale, started by Zoe Tweed’s poetic horn solo and culminating in a peroration with no lack of spectacle. It made an imposing end to this varied and cohesive concert, one that confirmed Shelley as a conductor with whom to reckon.

For details on the 2024-25 season A Season of Joy, head to the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra website. Click on the names to read more about violinist Hyeyoon Park, and conductor Alexander Shelley, or for more on composer Florence Price

Published post no.2,453 – Saturday 22 February 2025