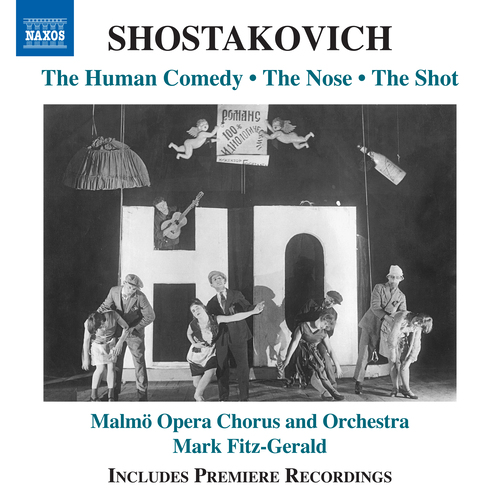

Tor Lind (bass), Kenny Staškus Larsen (flute), Allan Sjølin, Jesper Sivebaek (balalaikas), Edward Stewart (guitar) (all soloists in The Shot); Lars Notto Birkeland (organ, The Nose); Christian Enarsson (piano, The Human Comedy); Malmő Opera Chorus and Orchestra / Mark Fitz-Gerald

Shostakovich

The Shot – incidental music, Op.24 (1929)

The Human Comedy – incidental music, Op. 37 (1933-4)

The Nose, Op. 15 – appendix (1927-8)

The Vyborg Side, Op. 50 – March of the Arnachists (1938)

Naxos 8.574590 [56’42’’]

Russian text & English translation included

Producer Sean Lewis

Recorded 5-7 March at Opera House, Malmő and 4 April 2024 at Fagerborg Church, Oslo (The Nose)

Reviewed by Richard Whitehouse

What’s the story?

Naxos continues its ground-breaking series devoted to Shostakovich’s film and theatre scores, given with conviction by the Malmö Opera Orchestra and authoritatively conducted by Mark Fitz-Gerald, who has edited and often reconstructed these pieces from their surviving sources.

What’s the music like?

It is all too easily overlooked that, prior to being one of the leading composers of symphonies and string quartets from the 20th century, Shostakovich became established primarily through music for the theatre and cinema; in the process, he frequently transferred musical ideas from one medium to the other. The present release features the complete incidental music from two of his most ambitious such undertakings, along with hitherto unknown passages from his first opera and an item from one of his film scores – much of this material recorded for the first time.

Shostakovich’s first assignment for Leningrad-based TRAM (Theatre of Working Youth), his incidental music for Aleksandr Bezymensky’s verse-drama The Shot had a fraught rehearsal process prior to its relatively successful first-run. Few of the mainly brief numbers survived intact but the outcome, as reconstructed from piano sketches, is a lively if not overly anarchic score – highlights being the Mussorgskian pastiche ‘Workers’ Song of Victory’ (track 1) and the poignant ‘Dun’dya’s Lament’ (16) with its guitar part deftly restored by Edward Stewart.

Some five years on and the experimental zeal of Soviet theatre had largely evaporated, hence the music for Moscow-based Vakhtangov Theatre’s production The Human Comedy. Adapted by Pavel Sukhotin from Honoré de Balzac’s epic, its essence seems one of nostalgia for things past – typified by the theme, nominally evoking Paris, which Shostakovich threads across his half-hour score. Complementing this are more animated or even uproarious numbers, several of which found their way into those Ballet Suites latterly assembled in Stalin’s twilight years.

The programme is rounded out, firstly, with three fragments from The Nose – the undoubted masterpiece of Shostakovich’s radical years. Taken from each of its acts, they pursue musical directions likely impractical in a theatrical context; though what was intended as an overture to Act Three (41) could still make its way as a scintillating encore. Finally, the ‘March of the Anarchists’ (43) from the film The Vyborg Side: reconstructed from its original soundtrack, it finds the composer remodelling music from Weill’s The Threepenny Opera in his own image.

Do the performances work?

Pretty much throughout – accepting, of course, the fragmentary nature of the two main works as determined by their function. In particular, the five-movement suite assembled – not by the composer – from The Human Comedy (and recorded by Edward Serov with the St Petersburg Chamber Orchestra for Melodiya) brings together various of those individual pieces to more cohesive overall effect. Not that the present performances are at all wanting in expertise and conviction, making for an album which is a necessary listen for all admirers of this composer.

Is it recommended?

Very much so. The booklet features detailed notes from no less than Gerard McBurney, with a brief contextual note by Fitz-Gerald. Hopefully there will be further such releases from this source, and not forgetting that several of Shostakovich’s film scores have still to be recorded.

Listen / Buy

You can hear excerpts from the album and explore purchase options at the Naxos website, or you can listen to the album on Tidal. Click to read more about Mark Fitz-Gerald’s recordings for Naxos, the Malmő Opera Orchestra and the Shostakovich Centre.

Published post no.2,792 – Sunday 8 February 2026