Natalya Romaniw (soprano, below), City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra / Eduardo Strausser (above)

Shekhar Lumina (2020) [UK Premiere]

Richard Strauss Vier letzte Lieder (1948)

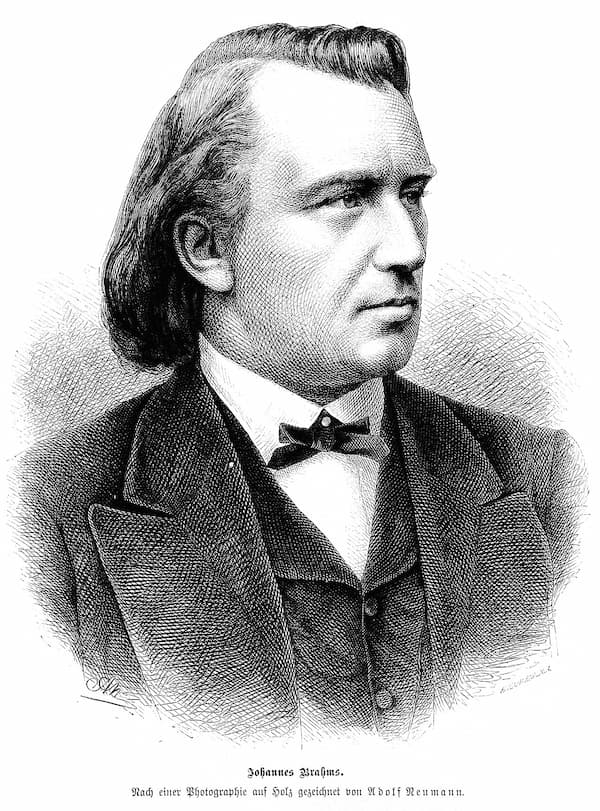

Brahms Symphony no.4 in E minor Op.98 (1884-5)

Symphony Hall, Birmingham

Wednesday 4 February 2026

Reviewed by Richard Whitehouse Pictures (c) Rodrigo Levy (Eduardo Strausser), Frances Marshall (Natalya Romaniw)

Eduardo Strausser has been welcome visitor to the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra on several earlier occasions (see elsewhere on this website), with this afternoon’s programme demonstrating a keen ear for his juxtaposing of contemporary music and established classics.

Equally well-established as an instrumentalist and multi-media artist, Nina Shekhar (b.1995) is an Indian-American with a substantial output to her credit – not least Lumina. Premiered in Los Angeles and subsequently heard across the United States, its eventful 12 minutes explore what she has described as ‘‘… the spectrum of light and dark and the murkiness in between’’. The incremental emergence of sound and texture brings Ligeti’s 1960s pieces to mind, while the build-up of its central phase towards a culmination of palpable emotional fervour is both adeptly managed and powerfully sustained, before the gradual return to its inward origin. The present performance left little doubt as to Strausser’s belief in this music, even if that opening stage would have benefitted from a more attentive response by some of those in the audience.

Richard Strauss’s Four Last Songs is too frequently encountered in concert these days, so that it takes something special to make one reflect anew on its achievement as among the greatest of musical swansongs. This account got off to rather an inauspicious start – Natalya Romaniw overwrought in the vernal deftness of Frühling, not aided by overly opaque textures – though it subsequently came into its own. Arguably the most perfectly realized of all orchestral songs, September found an enticing balance between joy and resignation, while if leader Jonathan Martindale’s solo in Beim Schlafengehen was not quite flawless, it eschewed sentimentality to a (surprisingly?) rare degree. Im Abendrot rounded off the performance with Romaniw’s eloquent retreat into an orchestral backdrop which itself faded into serene and rapt fulfilment.

If by no means his final work, Brahms’s Fourth Symphony surely marks the onset of his final creative period. In its overtly austere sound-world and an abundance of hymn-like or chorale-inflected themes, it is also the most Bachian of his orchestral works but Strausser was right to offset this aspect against that surging emotion as underlies even the most speculative passages of its opening movement. The coda built methodically yet not a little impulsively towards an apotheosis as dramatic as anything by this most Classically inclined of Romantic composers.

After this, the Andante emerged in all its autumnal warmth and expressive poignancy – if not the most perfectly realized Brahms slow movement then surely the most profound. Bracingly energetic if never headlong, the scherzo prepared unerringly for the finale – the effectiveness of its passacaglia format having on occasion been questioned, while conveniently overlooking that parallel sonata-form dynamism such as galvanizes this movement on its intended course. Suffice to add that the closing pages felt as inevitable as any performance in recent memory.

Overall, a fine showing for the CBSO – notably its woodwind and brass – and Strausser, who will hopefully return soon. The orchestra is heard later this month with Omar Meir Wellber in a no less stimulating programme of Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto with Haydn’s ‘Nelson’ Mass.

To read more about the CBSO’s 2025/26 season, visit the CBSO website. Click on the names for more on conductor Eduardo Strausser soprano Natalya Romaniw and composer Nina Shekhar

Published post no.2,791 – Saturday 7 February 2026